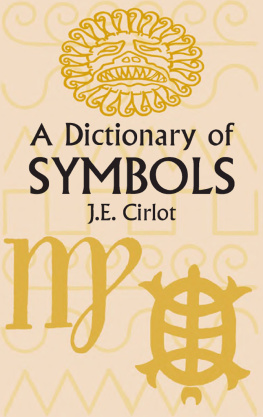

A DICTIONARY OF SYMBOLS

A

DICTIONARY

OF SYMBOLS

Second Edition

by

J.E. CIRLOT

Translated from the Spanish by

JACK SAGE

Foreword by Herbert Read

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2002, is an unabridged republication of the second edition of the work, translated from the Spanish by Jack Sage, and originally published by the Philosophical Library, Inc., New York, in 1971.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cirlot, Juan Eduardo.

[Diccionario de smbolos tradicionales. English]

A dictionary of symbols / J.E. Cirlot; translated from the Spanish by Jack Sage; foreword by Herbert Read.

p. cm.

Originally published: 2nd ed. New York : Philosophical Library, 1971.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-486-42523-1 (pbk.)

1. SymbolismDictionaries. I. Title.

BF1623.S9 C513 2002

302.222303dc21

2002022956

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y 11501

PLATES

Between pages 104 and 105

Between pages 296 and 297

FOREWORD

IN THE INTRODUCTION to this volume Seor Cirlot shows his wide and learned conception of the subject-matter of this dictionary, and the only task left to me is to present the author himself, who has been familiar to me for some years as the leading protagonist of a very vital group of painters and poets in Barcelona. Juan Eduardo Cirlot was born in Barcelona in 1916, and after matriculating from the College of the Jesuits there, studied music. From 1943 onwards he was active as a poet, and published four volumes of verse between 1946 and 1953. Meanwhile the group of painters and poets already mentioned had been formed (Dau al Set), and Cirlot became its leading theoretician. For historical or political reasons, Spain had been slow to develop a contemporary movement in the arts comparable to those in other European countries; its greatest artists, Picasso and Mir, had identified themselves with the School of Paris. But now a vigorous and independent School of Barcelona was to emerge, with Antonio Tapies and Modesto Cuixart as its outstanding representatives. In a series of books and brochures Cirlot not only presented the individual artists of this group, but also instructed the Spanish public in the history and theoretical foundations of the modern movement as a whole.

In the course of this critical activity Seor Cirlot inevitably became aware of the symbolist ethos of modern art. A symbolic element is present in all art, in so far as art is subject to psychological interpretation. But in so far as art has evolved in our time away from the representation of an objective reality towards the expression of subjective states of feeling, to that extent it has become a wholly symbolic art, and it was perhaps the necessity for a clarification of this function in art which led Seor Cirlot to his profound study of symbolism in all its aspects.

The result is a volume which can either be used as a work of reference, or simply read for pleasure and instruction. There are many entries in this dictionarythose on Architecture, Colour, Cross, Graphics, Mandala, Numbers, Serpent, Water, Zodiac, to give a few exampleswhich can be read as independent essays. But in general the greatest use of the volume will be for the elucidation of those many symbols which we encounter in the arts and in the history of ideas. Man, it has been said, is a symbolizing animal; it is evident that at no stage in the development of civilization has man been able to dispense with symbols. Science and technology have not freed man from his dependence on symbols: indeed, it might be argued that they have increased his need for them. In any case, symbology itself is now a science, and this volume is a necessary instrument in its study.

HERBERT READ

INTRODUCTION

ACTUALITY OF THE SYMBOL

Delimitation of the Symbolic On entering the realms of symbolism, whether by way of systematized artistic forms or the living, dynamic forms of dreams and visions, we have constantly kept in mind the essential need to mark out the field of symbolic action, in order to prevent confusion between phenomena which might appear to be identical when they are merely similar or externally related. The temptation to over-substantiate an argument is one which is difficult to resist. It is necessary to be on ones guard against this danger, even if full compliance with the ideals of scholarship is not always feasible; for we believe with Marius Schneider that there is no such thing as ideas or beliefs, only ideas and beliefs, that is to say that in the one there is always at least something of the otherquite apart from the fact that, as far as symbolism is concerned, other phenomena of a spiritual kind play an important part.

When a critic such as Caro Baroja (10) declares himself against any symbolic interpretation of myth, he doubtless has his reasons for so doing, although one reason may be that nothing approaching a complete evaluation of symbolism has yet appeared. He says: When they seek to convince us that Mars is the symbol of War, and Hercules of Strength, we can roundly refute them. All this may once have been true for rhetoricians, for idealist philosophers or for a group of more or less pedantic graeculi. But, for those who really believed in ancient deities and heroes, Mars had an objective reality, even if this reality was quite different from that which we are groping for today. Symbolism occurs when natural religions are degenerating. In point of fact, the mere equation of Mars with War and of Hercules with Labour has never been characteristic of the symbolist ethos, which always eschews the categorical and restrictive. This comes about through allegory, a mechanical and restricting derivative of the symbol, whereas the symbol proper is a dynamic and polysymbolic reality, imbued with emotive and conceptual values: in other words, with true life.

However, the above quotation is extremely helpful in enabling us to mark out the limits of the symbolic. If there is or if there may be a symbolic function in everything, a communicating tension, nevertheless this fleeting possession of the being or the object by the symbolic does not wholly transform it into a symbol. The error of symbolist artists and writers has always been precisely this: that they sought to turn the entire sphere of reality into a vehicle for impalpable correspondences, into an obsessive conjunction of analogies, without being aware that the symbolic is opposed to the existential and instrumental and without realizing that the laws of symbolism hold good only within its own particular sphere. This distinction is one which we would also apply to the Pythagorean thesis that everything is disposed according to numbers, as well as to microbiological theory. Neither the assertion of the Greek philosopher on the one hand, nor the vital pullulation subjected invisibly to the science of Weights and Measures on the other, is false; but all life and all reality cannot be forced to conform with either one theory or the other, simply because of its certitude, for it is certain only within the limits of theory. In the same way, the symbolic is true and active on one plane of reality, but it is almost unthinkable to apply it systematically and consistently on the plane of existence. The consequent scepticism concerning this plane of realitythe magnetic life-source of symbols and their concomitantsexplains the widespread reluctance to admit symbolical values; but such an attitude is lacking in any scientific justification.

Next page