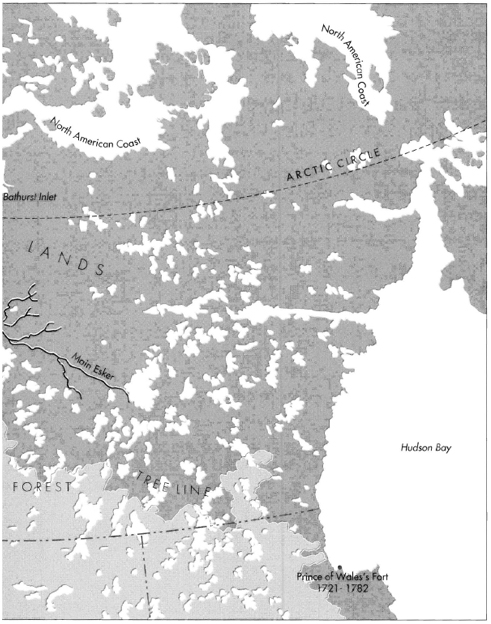

Barren Lands

An Epic Search for Diamonds in the North American Arctic

KEVIN KRAJICK

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

First Edition published 2001 by Henry Holt and Company.

Copyright 2001, 2013 by Kevin Krajick

ISBN: 978-1-5040-2916-2

Distributed in 2016 by Open Road Distribution

180 Maiden Lane

New York, NY 10038

www.openroadmedia.com

FOR

RUBY, STELLA AND LYDIA

Man puts an end to darkness, and searches every recess for ore in the darkness and the shadow of death. He breaks open a shaft away from people, in places where there is no foothold, and hangs suspended far from mankind. That earth from which bread comes is ravaged underground by fire. Down there, the rocks are set with sapphires, full of spangles of gold. Down there is a path unknown to birds of prey, unseen by the eye of any vulture; a path not trodden by the lordly beasts, where no lion ever walked. Man attacks its flinty sides, upturning mountains by their roots, driving tunnels through the rocks, on the watch for anything precious. He explores the sources of rivers, and brings to daylight secrets that were hidden. But tell me, where does wisdom come from? Where is understanding to be found?

J OB 28: 312

It is the ambition of every prospector to unroll the map northwards.

B ERTRAM B ARKER , N ORTH OF 53

Barren Lands was originally published by Henry Holt and Company in 2001. The present e-book edition contains a small number of corrections and clarifications, along with updated notes and a newly written epilogue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to the memories of diamond seekers and Arctic adventurers past and present, nothing here is fictionalized. As far as I know, this is the way it happened. From southern Africa to the Arctic Ocean, many shared details of their lives, dug out their memoirs, and physically retraced their steps. Several guarded my well-being in some dangerous places.

Nearly every living character helped in the research. Their names are obvious in the text, but special thanks are due to Chuck Fipke, Stewart Blusson, Hugo Dummett, John Gurney, Tom McCandless, Chris Jennings, Brent Carr, Paul Derkson, Mike Waldman, Ray Ashley, Fred Sangris, and Moise Rabesca. Deep thanks also to their various parents, spouses, children, brothers, and sisters, who gave much. People at BHP Diamonds helped often, especially Rory Moore and Chris Hanks. De Beers Consolidated Mines has a fierce reputation for secrecy, yet current and exDe Beers scientists welcomed my interest and volunteered many previously hidden facts about their work. They include Barry Hawthorne, Mousseau Tremblay, Joe Brunet, and Craig Smith. Three most important northern guides hardly appear in the text, but their spirits are there: Steve Matthews and Tom Andrews of Yellowknife and Allen Niptanatiak of Kugluktuk. I bless them all and trust none will get into trouble for what they revealed.

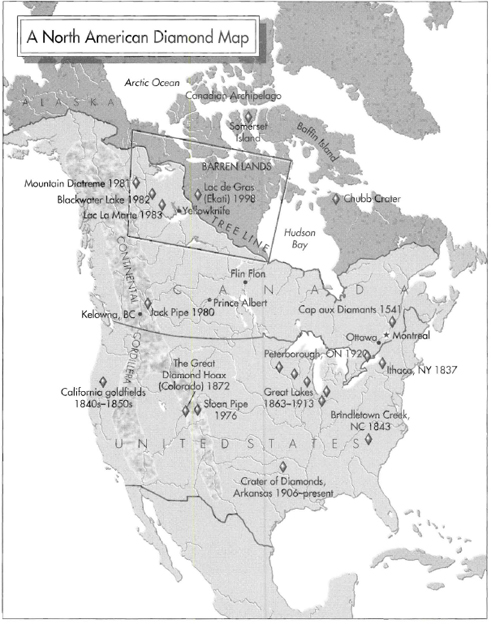

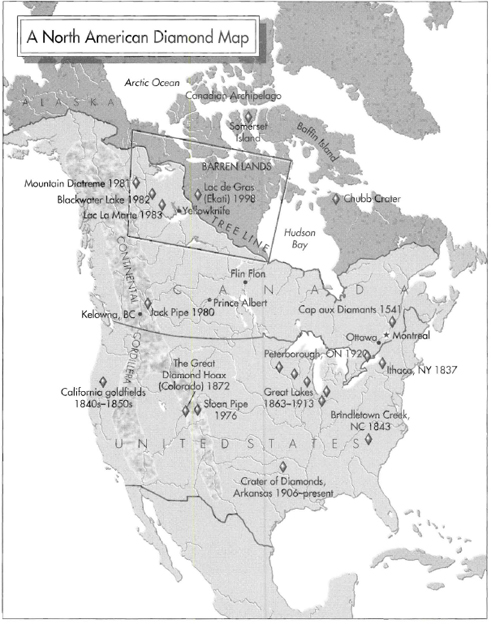

A large amount of history is contained in these pages. Whenever possible I used primary sources: maps, diaries, newspapers, scientific articles. The Geological Survey of Canada (GSC), whose work quietly helped set the stage for the northern diamond rush, provided piles of material via Walter Nassichuk, Ron DiLabio, Bruce Kjarsgaard, and many others. Unique historical documents came also from generous colleagues at the state geologic surveys of Wyoming, Wisconsin, Arkansas, Colorado, Maine, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Montana, New York, Ohio, Virginia, Georgia, and North Carolina. Rare memoirs of the Barren Lands were provided by the Archives of the Northwest Territories and the wonderful Yellowknife Public Library. The New York Public Library and the geology library of Columbia University were incomparable sources of old books and articles on diamond prospecting.

My first opportunity to journey to the Barrens came in the summer of 1994, when I reported on the diamond rush for Discover magazine; later pieces for Newsweek, Audubon, and Natural History furthered my research. My agent, Regula Noetzli, spent two years finding a publisher for this book. W. H. Freemans Holly Hodder finally accepted the project, and it was greatly strengthened by editor Erika Goldman and the hard work of Mary Louise Byrd, Bob Podrasky, Michele Kornegay, Susan Goldstein, and T.J. Fitzgerald. Ex-GSC man William Shilts and W. Dan Hausel of the Wyoming Geological Survey served as expert advisers, preventing many mistakes.

Three people deserve the most thanks of all: my parents, Katherine Distin Krajick and Rudolph Adam Krajick, who always encouraged me to go wherever curiosity led; and my wife, Ruby, who stood behind me no matter what. When I disappeared for weeks into the tundra and then for months into my office, it caused her worry and hardship, I know, but she was there always.

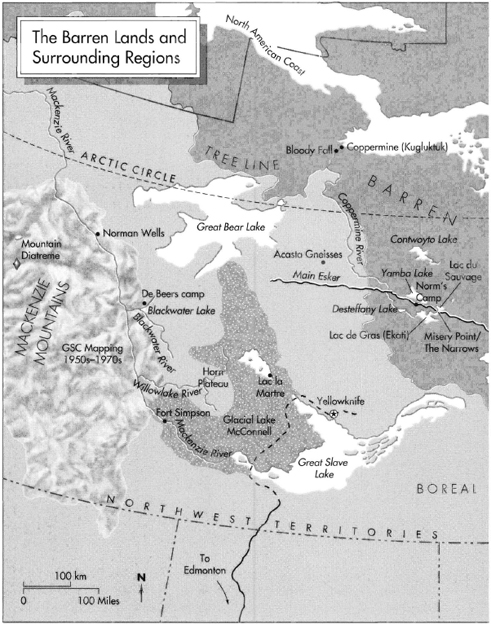

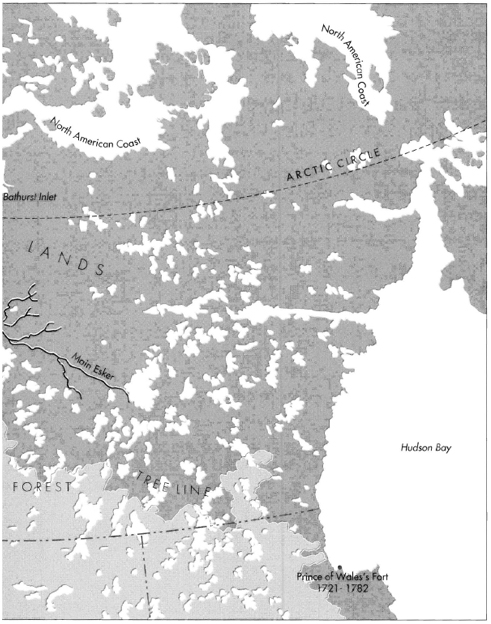

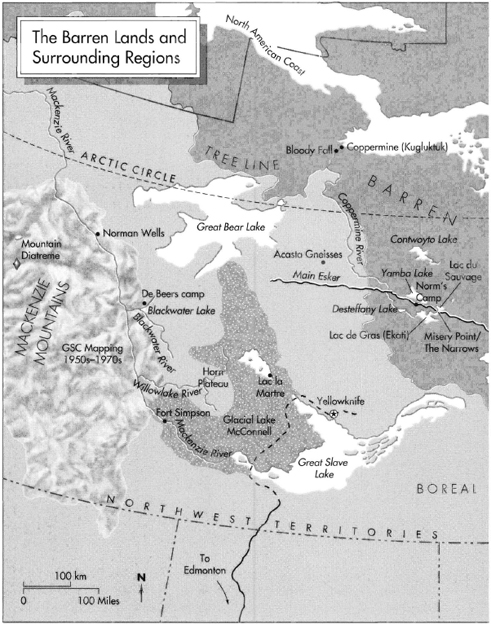

I narrate here the deaths of some fellow human beings. To their loved ones: I tried to do this with the greatest respect. I also mean no disrespect to the people of the north by locating the Barren Lands wholly within Canadas Northwest Territories. In 1999 the northern half of the Territories, and thus roughly half the Barrens, became Nunavut, homeland of the Inuit. All events described here took place before then.

Prologue: Heading North

Having neglected to bring a pickax on this particular trip, Charles E. Fipke was nearing the bottom of a seven-and-a-half-foot hole in the snow and ice by tearing at some rocks with the small pick-end of a geologists hand hammer. His son Mark was at the distant top, shouting down curses about the cold, the wind, the risk of dying, and the uselessness of it all.

Fipke ignored him. It was his own turn to dig. It had taken them five hours to get down this far, and, as usual, he was not going to stop until he got what he wanted: a twenty-pound bag of sand and gravel from the frozen earth at the bottom. Twelve years into this mad prospecting enterprise there seemed to be no end in sight. That is, unless you considered the empty bank account, the crystals of wind-driven snow now eroding their faces, the cold progressing up their limbs, and the fact that they were a several-week walk from town in the middle of the tundra.

Fipke had picked the shoreline of an unnamed little lake to dig, based on a glimpse of it from the air the day before. With their last dollars, they had chartered a $600-an-hour helicopter and flown here to follow up the tantalizing clues of earlier trips and at long last to stake out their claims. Millions of frozen tundra lakes, covered with snow and pocked with lichen-blackened boulders around the shores, looked the same from the airexcept this one, sitting in its own craterlike depression, a bit more circular than the others. On both the north and south shorelines, dark, unusual cliffs dropped straight to the ice, as if someone had drilled a hole in the bedrock. In camp that night a dozen miles off, Fipke could not sleep. Every time he closed his eyes, he would see the lake with the two dark cliffs on opposite shores, plunging to the ice.