Introduction

Introduction

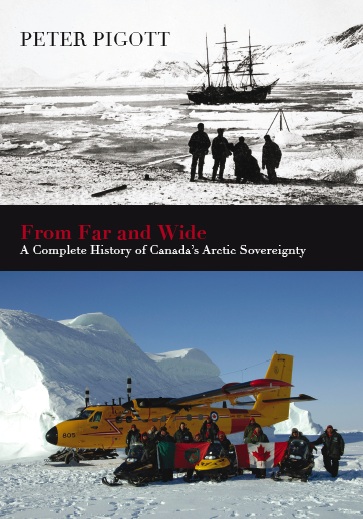

F rom Far and Wide is a play in six acts. The stage setting and the backdrop remain the same throughout while the players enter in period costume, perform their lines, and exit. The arrangement of scenery and props is intended to depict the Canadian Arctic from the 60th parallel as far north as Herschel Island in the west to the Lincoln Sea in the east. The painted backdrop could thus be icebergs, pack ice, mountains, glaciers, coastal plains, muskeg, or Baffin Island cliffs. The few props will range from simple canvas tents to empty meat tins to 1927 Fokker monoplanes to giant golf balllike antenna.

Because this is the Arctic, the lighting will vary from high intensity to almost pitch-blackness. It will initially illuminate each scene and then a spotlight will focus on the individual central to the period be it Sir John Franklin, Sir George Simpson, Clifford Sifton, or John Diefenbaker, keeping the remainder of the stage dark while he speaks of his particular vision for the Arctic. If the theatre company possesses the resources and technical wizardry to create the magnificence of the aurora borealis, so much the better.

As stage lighting tends to remove definition from a face, cosmetic makeup is essential, especially in Acts One through Three. Haggard features etched by scurvy and disease can be created by emphasizing cheekbones, eye sockets to portray hollowed faces. Alternately, sunburn and sun blindness in such a frigid climate would cause swollen eyes and lips and the appearance of each actor in these scenes is to be made up with reddish greasepaint, creating the effect of as if boiling water had been poured on his head.

At times the action will move away from centre stage to the Norwegian or the Alaskan Arctic, or a river in the Yukon. As this is a historical drama, the dialogue and costumes of the all-male cast are appropriate to their time period. This will vary from British naval officers of the 1840s to North-West Mounted Police constables in 1898 to Prime Minister Mackenzie King in the 1940s to that of American servicemen of the 1950s, culminating with the Canadian Forces Frozen Chosen in 2010. By far the most difficult task for the actors will be conveying to the audience the ever present, bone-chilling cold. Intermittently, there will be voices heard offstage, ostensibly coming from diplomats, prime ministers, and interested parties (like Lady Franklin) in London, Ottawa, Oslo, and Washington.

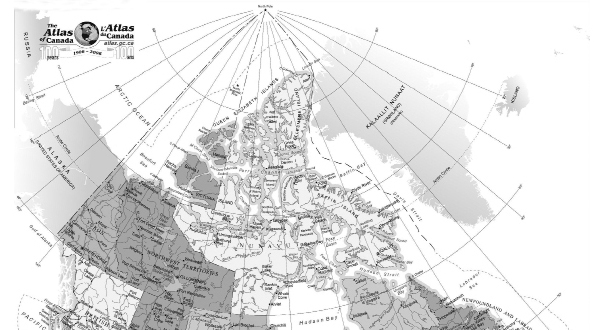

The audience will soon discern that the singular thread that runs through all six acts is the quest for sovereignty over 40 percent of Canadas land mass and more than 19,000 islands in the Arctic Archipelago. The actors will discuss exploration of the Arctic and protecting what they have mapped (and thus claimed for their sovereign) from the other polar neighbours such as Denmark, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States. Their incentives to risk their lives in the harshest climate on the planet will range from sheer obsession about conquering the Northwest Passage to moiling for gold to protecting the Arctics fragile ecosystem.

Then, below the footlights, but crucial to the play, would be the Aboriginals of the Canadian Arctic the Inuit. Referred to in early scenes as Esquimaux or Eskimo , until the last pages of Act Six, they are to be treated indifferently by those on stage. But unlike them, the Inuit are dressed appropriately for the Arctic: in double-layer trousers and waterproof parkas (double-layer pullover jackets with hoods) made of skins and furs.

Beginning as a mystery, the play is Canadas own Norse saga, an epic of adventure over two centuries, populated by men who were sometimes arrogant, greedy, and careless of their circumstances, but were always brave and determined. It wasnt that ignorance was bliss or uncertainty adventurous, but that for many who ventured into the Arctic, both would prove deadly. They were the astronauts of their day, and the Arctic was their moon.

It is hoped that the audience will come away from From Far and Wide with the realization that 90 percent of sovereignty is stewardship and that all sovereign rights of Arctic lands and waters by the government of Canada is owed to British exploration in the post-Napoleonic era and Inuit use and occupation of Inuit Nunangat since time immemorial.

The germ of From Far and Wide arose when I worked in the Treaty Section of the Department of Foreign Affairs. The original texts of all treaties that Canada is party to were stored in the Treaty Vault and, in my opinion, no other room in the Lester B. Pearson Building holds so much of the history of our countrys foreign relations even before it was a country. Within the banal facades of mobile shelving were rows of manila folders containing the original texts of agreements, conventions, protocols, declarations, memoranda of understanding, and Exchange of Notes. On all except the very recent, the signatures had faded, the vellum aged from translucent to opaque, the wax seals brittle and cracked.

I romanticized the language of the treaties and the choreography of their signing ceremonies. As historys great accomplishments, from the age of calligraphy to computers, they were proof that nations could come together to protect migratory birds, combat cyber-crime, or disarm their nuclear arsenals. Some treaties had been signed in the grandeur of Versailles or on the decks of battleships, while others were sealed in hitherto unknown places like Kyoto, Doha, or Schengen or Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, the summer residence of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. For it was here on July 31, 1880, that all British territories and possessions in North America were given to the Dominion of Canada the biggest land transfer in history. Within the legalese of the relevant Arctic treaties some of which are reproduced in the book, is the subtlety and dynamism of our countrys history.

Considering that most of us are more familiar with the beaches of Florida or Cuba, it is curious that a majority of Canadians consider the Arctic to be a cornerstone of national identity. In its survey for the Munk School of Global Affairs, EKOS Research Associates discovered that we see the Arctic as an integral part of our sense of national identity and favour protecting it with the military if need be. Another poll reveals that Canadians think the region should be the nations top foreign policy priority for the military far ahead of NATO or UN commitments.

Explored and mapped by the Royal Navy seeking a passage to the east, then transferred to the Dominion of Canada, the Arctic remained terra incognita until the air age. Although it could not have comprehended the size of the territorial windfall it had received, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie accepted the transfer if only to keep the United States and Czarist Russia out. But as the Dominion expanded along its east-west axis (dictated by the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway), the gift was forgotten. Except for the whaling, fishing, and fur industries, the potential of the North remained unknown. It was as one astute Canadian statesman observed: for later.