Stories of Canada

Discovering the Arctic

The Story of John Rae

by

John Wilson

Illustrations by Liz Milkau

Series editor: Allister Thompson

Napoleon Publishing

Text copyright 2003 by John Wilson Illustrations copyright 2003 Liz Milkau

All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the publisher.

Napoleon Publishing

Toronto Ontario Canada

www.napoleonpublishing.com |  |

Napoleon Publishing acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for our publishing program. We acknowledge the support of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative.

Printed in Canada

For Iain

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Wilson, John (John Alexander), date

Discovering the Arctic : the story of John Rae / John Wilson.

ISBN 0-929141-88-1

1. Rae, John, 1813-1893--Juvenile literature. 2. Arctic regions--Discovery and exploration--British--Juvenile literature. 3. Explorers--Scotland--Biography--Juvenile literature. 4. Explorers--Arctic regions--Biography--Juvenile literature. I. Title.

FC3961.1.R33W54 2003

G635.R25W54 2003 | j917.19041092 | C2003-902842-9 |

Contents

Into the Unknown

On a blustery June day in 1833, the small sailing vessel, Prince of Wales, left Stromness Harbour on the Orkney Islands north of Scotland. On her deck stood a nineteen-year-old, newly graduated doctor. As the ship began to roll in the choppy grey waters of the North Atlantic, he gazed westward as if trying to see what the future held.

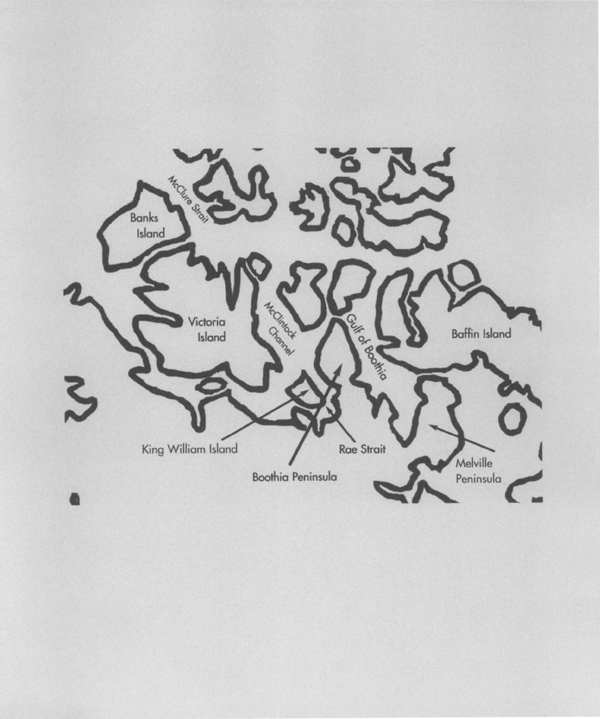

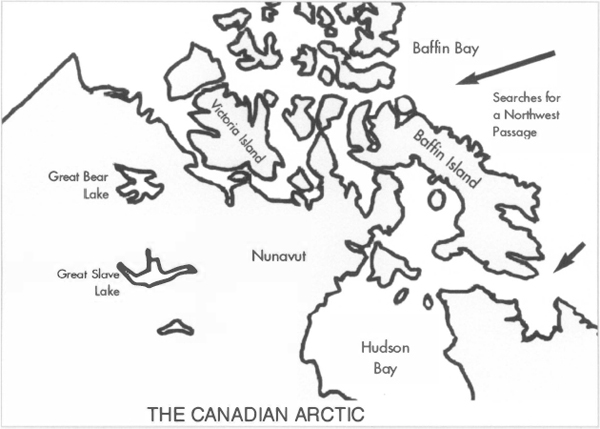

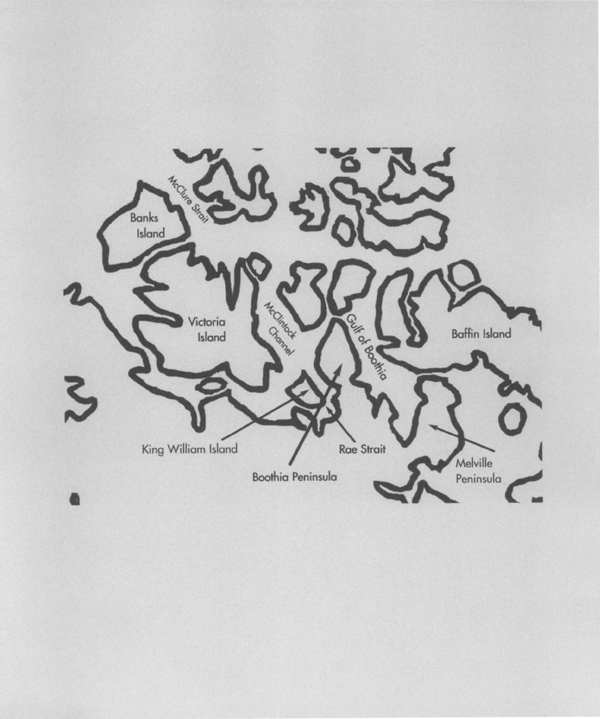

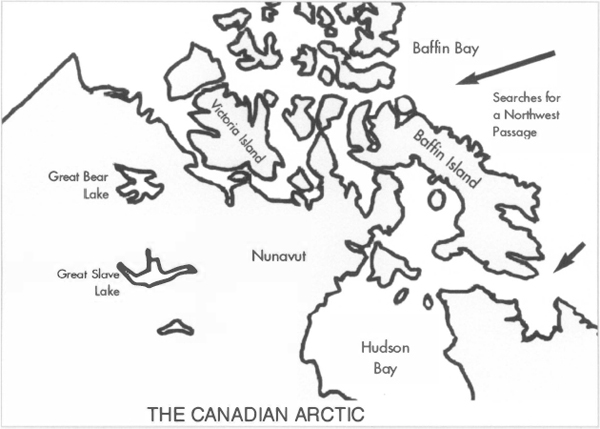

Ahead was Cape Farewell, the southernmost tip of Greenland. From there, a ship could turn north into the frozen wastes of Baffin Bay, south to the fishing grounds of Newfoundland and Labrador, or west into the turbulent, ice-filled waters of Hudson Strait. The Prince of Wales would turn west, into Hudson Bay, the gateway to the fur-rich but still largely unexplored interior of Canada.

There were opportunities for a young Orkney man prepared to work hard and learnand John Rae was prepared to do both. But even in his wildest dreams, he could not have foreseen the dramatic successes and unjust disappointments that lay ahead.

In voyaging west from Stromness, Rae was following in the footsteps of many famous men. Martin Frobisher, Henry Hudson, James Cook and Edward Parry had all used Logins Well in the centre of town to replenish their fresh water and the sturdy Orkney men to replace missing crew members. Stromness was often the last sight of home for many years. For John Franklin and his crew, who passed through twelve years after John Rae, it was the last sight of home any of them would ever have.

Plans and Reality

In 1833, John Rae planned on spending a year working for the Hudsons Bay Company (HBC), getting some experience, and having a bit of an adventure. He would have been surprised to learn that it would be more than a quarter of a century before he returned to live in his homeland and a full fourteen years before he even set foot there again.

In that time, Rae would walk, sledge or sail through thousands of kilometres of Canadas remote and inhospitable Arctic. He would learn to live like the Inuit, discover the tragic fate of Sir John Franklins doomed expedition and stand on the shore of the fabled Northwest Passage.

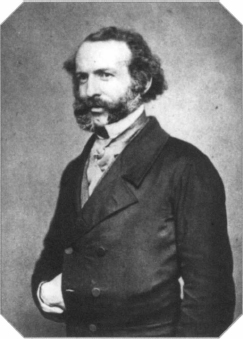

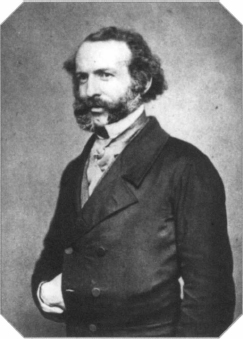

John Rae

Rae didnt know it, but he was on his way to becoming the most successful and resourceful Arctic traveller of his age. But he was also destined to feel the wrath of some of the most important people in England and to be passed over for the honours and recognition that fell to his less accomplished colleagues. It was a long, strange journey for a sensitive boy from the remote Orkney Islands.

Society in John Raes day was rigid and unyielding by todays standards. There was a correct way of doing everything, from eating your supper to exploring the Arctic. It was not necessarily the best way, but it was the way that powerful people had decided things should be done. If you did things differently, even if your way was better, you ran the risk of being ignoredor worse, hated.

The Ferrylouper

John Rae Sr., the explorers father, was a ferrylouper, or newcomer, to the Orkney Islands. He had been born and had grown up up in southern Scotland, near Glasgow, but his energy and a desire to better himself led him to accept a position looking after the estates and three hundred tenant farmers of Sir William Honeyman.

Sir William was Lord Armadale, a powerful figure in Scotland, and becoming his overseer in Orkney gave John Sr. status and a relatively comfortable life. However, he never took it for granted and expected his nine children to forge their own way in the world. Their challenge was to come to terms with the rugged moors and rocky coast of their island home, a process that instilled in the young John and his brothers and sisters a very independent spirit at an early age.

Only fifteen kilometres separate the seventy-four Orkney Islands from the Scottish mainland, yet it is in many ways a different world. In John Raes day during the stormy winter weather, it could take weeks to make the voyage to or from the mainland.

The Orkneys have been inhabited for at least six thousand years. Ancient villages, rings of huge standing stones, and chambered tombs litter the treeless landscape as reminders of vanished people. For hundreds of years, Orkney was part of the Norse empire and home to some of the Viking raiders who terrorized much of Europe a thousand years ago. These rough seafarers treasured their remote land so much that the Orkneys only became part of Scotland in 1474.

Extra Responsibility

Despite the security of his position with Lord Armadale, John Rae Sr.s drive would not let him rest. In 1819, he accepted the position of the Hudsons Bay Companys chief representative in Orkney. This meant that he oversaw the needs of the two or three company ships that visited each summer on their way across the Atlantic.

Next page