Copyright 2018 by Michael Palin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books Ltd.

greystonebooks.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-77164-441-9 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-77164-442-6 (epub)

Jacket design by Andrew Roberts and Nayeli Jimenez

Maps by Darren Bennett

Typesetting by Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd, Pondicherry

Greystone Books gratefully acknowledges the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples on whose land our office is located.

Greystone Books thanks the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada for supporting our publishing activities.

For Albert and Rose

And indeed, nothing is easier for a man who has, as the phrase goes, followed the sea with reverence and affection, than to evoke the great spirit of the past upon the lower reaches of the Thames. The tidal current runs to and fro in its unceasing service, crowded with memories of men and ships it had borne to the rest of home, or to the battles of the sea... from the Golden Hind returning with her round flanks full of treasure... to the Erebus and Terror, bound on other conquests and that never returned.

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

CONTENTS

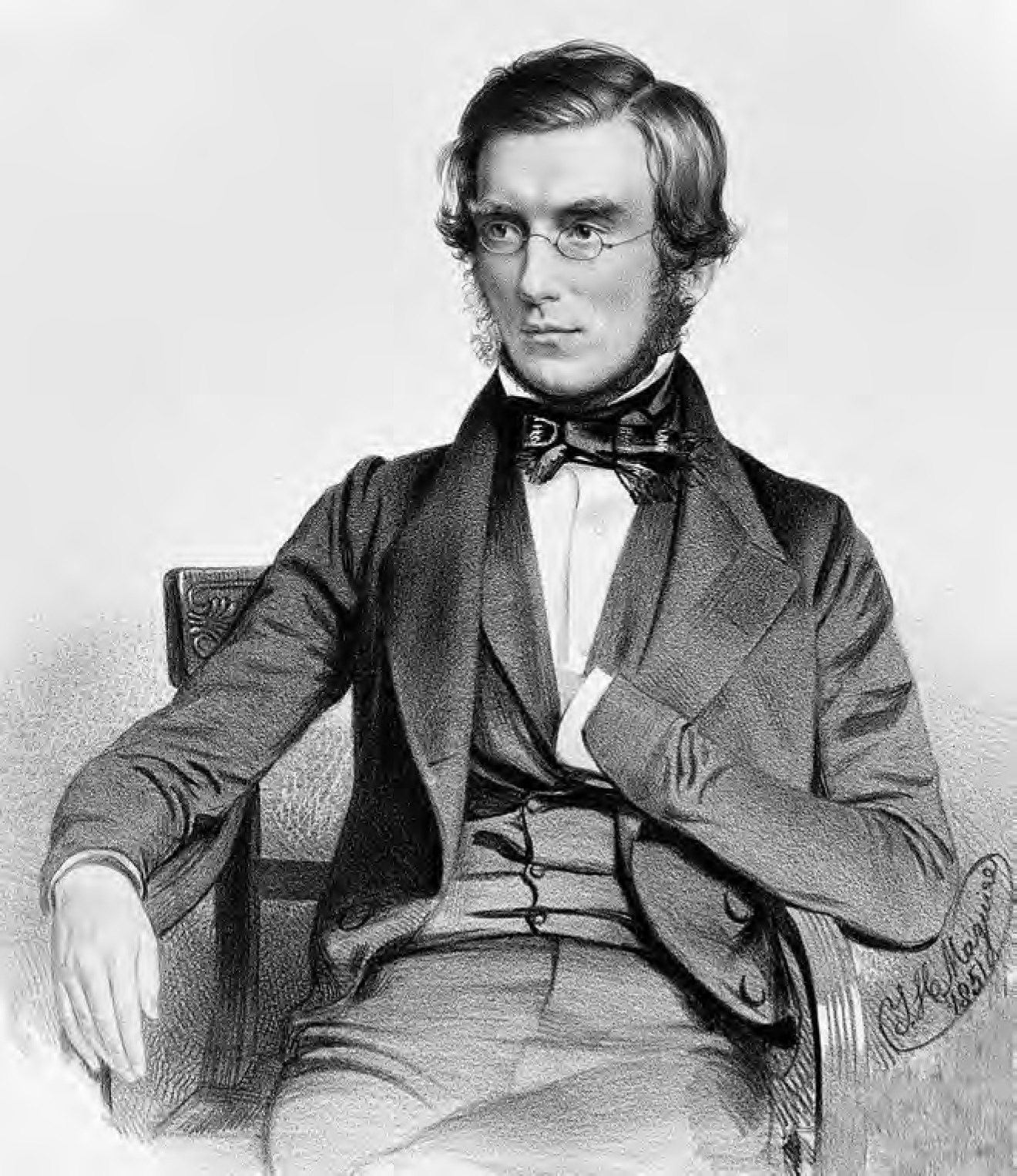

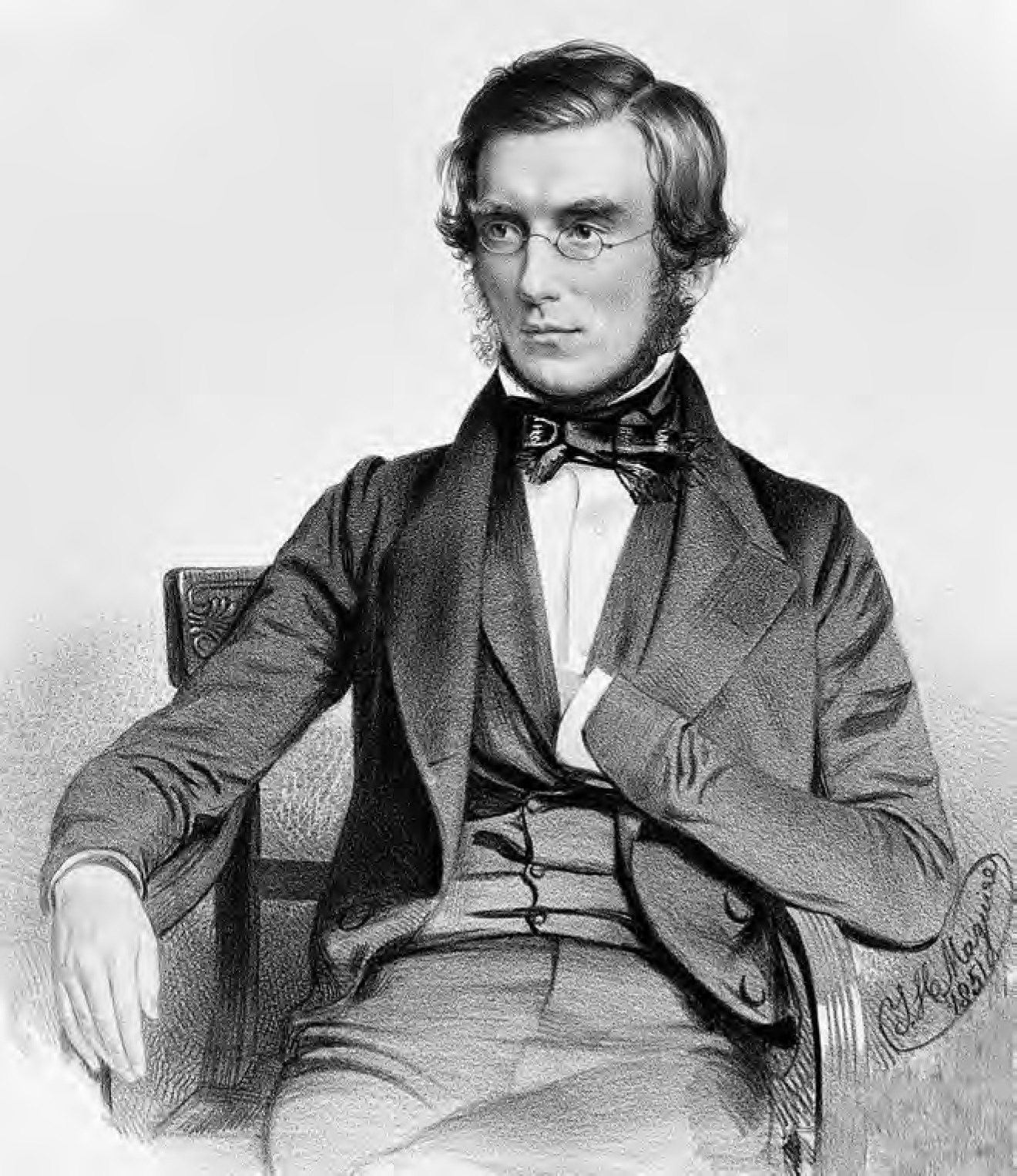

At the age of just twenty-two, Joseph Dalton Hooker joined the crew of HMS Erebus as assistant surgeon. He went on to become one of the greatest botanists of the nineteenth century.

INTRODUCTION

HOOKERS STOCKINGS

Ive always been fascinated by sea stories. I discovered C.S. Foresters Horatio Hornblower novels when I was eleven or twelve, and scoured Sheffield city libraries for any I might have missed. For harder stuff, I moved on to The Cruel Sea by Nicholas Monsarrat one of the most powerful books of my childhood, even though I was only allowed to read the Cadet edition, with all the sex removed. In the 1950s there was a spate of films about the Navy and war: The Sea Shall Not Have Them, Above Us the Waves, Cockleshell Heroes. They were stories of heroism, pluck and survival against all the odds. Unless you were in the engine room, of course.

As luck would have it, much later in life I ended up spending a lot of time on ships, usually far from home, with only a BBC camera crew and one of Patrick OBrians novels for company. I found myself, at different times, on an Italian cruise ship, frantically thumbing through Get By in Arabic as we approached the Egyptian coast, and in the Persian Gulf, dealing with an attack of diarrhoea on a boat whose only toilet facility was a barrel slung over the stern. Ive been white-water rafting below the Victoria Falls, and marlin-fishing (though not catching) on the Gulf Stream what Hemingway called the great blue river. Ive been driven straight at a canyon wall by a jet boat in New Zealand, and have swabbed the decks of a Yugoslav freighter on the Bay of Bengal. None of this has put me off. Theres something about the contact between boat and water that I find very natural and very comforting. After all, we emerged from the sea and, as President Kennedy once said, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea... we are going back to whence we came.

In 2013 I was asked to give a talk at the Athenaeum Club in London. The brief was to choose a member of the club, dead or alive, and tell their story in an hour. I chose Joseph Hooker, who ran the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew for much of the nineteenth century. I had been filming in Brazil and heard stories of how he had pursued a policy of botanical imperialism, encouraging plant-hunters to bring exotic, and commercially exploitable, specimens back to London. Hooker acquired rubber-tree seeds from the Amazon, germinated them at Kew and exported the young shoots to Britains Far Eastern colonies. Within two or three decades the Brazilian rubber industry was dead, and the British rubber industry was flourishing.

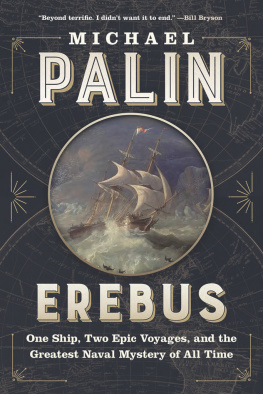

I didnt get far into my research before I stumbled across an aspect of Hookers life that was something of a revelation. In 1839, at the unripe age of twenty-two, the bearded and bespectacled gentleman that I knew from faded Victorian photographs had been taken on as assistant surgeon and botanist on a four-year Royal Naval expedition to the Antarctic. The ship that took him to the unexplored ends of the earth was called HMS Erebus. The more I researched the journey, the more astonished I became that I had previously known so little about it. For a sailing ship to have spent eighteen months at the furthest end of the earth, to have survived the treacheries of weather and icebergs, and to have returned to tell the tale was the sort of extraordinary achievement that one would assume we would still be celebrating. It was an epic success for HMS Erebus.

Pride, however, came before a fall. In 1846 this same ship, along with her sister ship Terror and 129 men, vanished off the face of the earth whilst trying to find a way through the Northwest Passage. It was the greatest single loss of life in the history of British polar exploration.

I wrote and delivered my talk on Hooker, but I couldnt get the adventures of Erebus out of my mind. They were still lurking there in the summer of 2014, when I spent ten nights at the 02 Arena in Greenwich with a group of fellow geriatrics, including John Cleese, Terry Jones, Eric Idle and Terry Gilliam, but sadly not Graham Chapman, in a show called Monty Python Live One Down Five to Go. These were extraordinary shows in front of extraordinary audiences, but after I had sold the last dead parrot and sung the last lumberjack song, I was left with a profound sense of anticlimax. How do you follow something like that? One thing was for sure: I couldnt go over the same ground again. Whatever I did next, it would have to be something completely different.

Two weeks later, I had my answer. On the evening news on 9 September I saw an item that stopped me in my tracks. At a press conference in Ottawa, the Prime Minister of Canada announced to the world that a Canadian underwater archaeology team had discovered what they believed to be HMS Erebus, lost for almost 170 years, on the seabed somewhere in the Arctic. Her hull was virtually intact, its contents preserved by the ice. From the moment I heard that, I knew there was a story to be told. Not just a story of life and death, but a story of life, death and a sort of resurrection.