CONTENTS

ABOUT THE BOOK

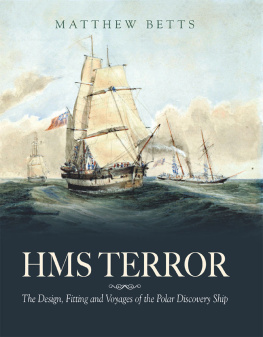

In September 2014 the wreck of a sailing vessel was discovered at the bottom of the sea in the frozen wastes of the Canadian arctic. It was broken at the stern and covered in a woolly coat of underwater vegetation. Its whereabouts had been a mystery for over a century and a half. Its name was HMS Erebus.

Now Michael Palin former Monty Python stalwart and much-loved television globetrotter brings this extraordinary ship back to life, following it from its launch in 1826 to the epic voyages of discovery that led to glory in the Antarctic and to ultimate catastrophe in the Arctic. He explores the intertwined careers of the men who shared its journeys: the dashing James Clark Ross who charted much of the Great Southern Barrier and oversaw some of the earliest scientific experiments to be conducted there; and the troubled John Franklin, who at the age of sixty and after a chequered career, commanded the ship on its final, disastrous expedition. And he vividly recounts the experiences of the men who first stepped ashore on Antarcticas Victoria Land, and those who, just a few years later, froze to death one by one in the Arctic ice, as rescue missions desperately tried to reach them.

The result is a wonderfully evocative account of one of the most extraordinary adventures of the nineteenth century, as reimagined by a master explorer and storyteller.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Palin has written and starred in numerous TV programmes and films, from Monty Python and Ripping Yarns to The Missionary and American Friends. He has also made several much-acclaimed travel documentaries, his journeys taking him to the North and South Poles, the Sahara Desert, the Himalayas, Eastern Europe and Brazil. His books include accounts of his journeys, novels (Hemingways Chair and The Truth) and several volumes of diaries. From 2009 to 2012 he was president of the Royal Geographical Society, and in 2013 he was made a BAFTA fellow. He lives in London.

For Albert and Rose

And indeed, nothing is easier for a man who has, as the phrase goes, followed the sea with reverence and affection, than to evoke the great spirit of the past upon the lower reaches of the Thames. The tidal current runs to and fro in its unceasing service, crowded with memories of men and ships it had borne to the rest of home, or to the battles of the sea from the Golden Hind returning with her round flanks full of treasure to the Erebus and Terror, bound on other conquests and that never returned.

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

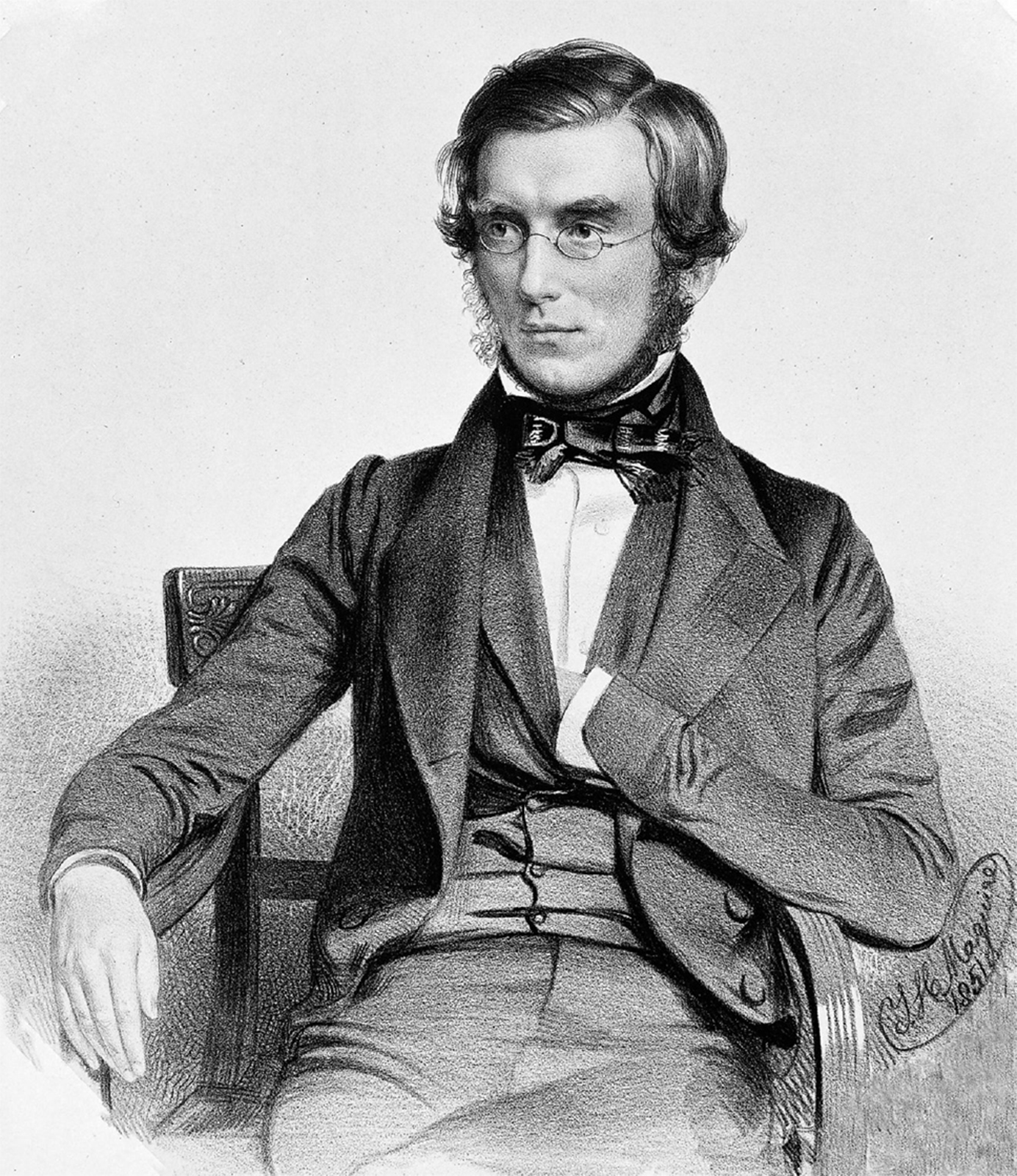

At the age of just twenty-two, Joseph Dalton Hooker joined the crew of HMS Erebus as assistant surgeon. He went on to become one of the greatest botanists of the nineteenth century.

INTRODUCTION

HOOKERS STOCKINGS

Ive always been fascinated by sea stories. I discovered C.S. Foresters Horatio Hornblower novels when I was eleven or twelve, and scoured Sheffield city libraries for any I might have missed. For harder stuff, I moved on to The Cruel Sea by Nicholas Monsarrat one of the most powerful books of my childhood, even though I was only allowed to read the Cadet edition, with all the sex removed. In the 1950s there was a spate of films about the Navy and war: The Sea Shall Not Have Them, Above Us the Waves, Cockleshell Heroes. They were stories of heroism, pluck and survival against all the odds. Unless you were in the engine room, of course.

As luck would have it, much later in life I ended up spending a lot of time on ships, usually far from home, with only a BBC camera crew and one of Patrick OBrians novels for company. I found myself, at different times, on an Italian cruise ship, frantically thumbing through Get By in Arabic as we approached the Egyptian coast, and in the Persian Gulf, dealing with an attack of diarrhoea on a boat whose only toilet facility was a barrel slung over the stern. Ive been white-water rafting below the Victoria Falls, and marlin-fishing (though not catching) on the Gulf Stream what Hemingway called the great blue river. Ive been driven straight at a canyon wall by a jet boat in New Zealand, and have swabbed the decks of a Yugoslav freighter on the Bay of Bengal. None of this has put me off. Theres something about the contact between boat and water that I find very natural and very comforting. After all, we emerged from the sea and, as President Kennedy once said, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea we are going back to whence we came.

In 2013 I was asked to give a talk at the Athenaeum Club in London. The brief was to choose a member of the club, dead or alive, and tell their story in an hour. I chose Joseph Hooker, who ran the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew for much of the nineteenth century. I had been filming in Brazil and heard stories of how he had pursued a policy of botanical imperialism, encouraging plant-hunters to bring exotic, and commercially exploitable, specimens back to London. Hooker acquired rubber-tree seeds from the Amazon, germinated them at Kew and exported the young shoots to Britains Far Eastern colonies. Within two or three decades the Brazilian rubber industry was dead, and the British rubber industry was flourishing.

I didnt get far into my research before I stumbled across an aspect of Hookers life that was something of a revelation. In 1839, at the unripe age of twenty-two, the bearded and bespectacled gentleman that I knew from faded Victorian photographs had been taken on as assistant surgeon and botanist on a four-year Royal Naval expedition to the Antarctic. The ship that took him to the unexplored ends of the earth was called HMS Erebus. The more I researched the journey, the more astonished I became that I had previously known so little about it. For a sailing ship to have spent eighteen months at the furthest end of the earth, to have survived the treacheries of weather and icebergs, and to have returned to tell the tale was the sort of extraordinary achievement that one would assume we would still be celebrating. It was an epic success for HMS Erebus.

Pride, however, came before a fall. In 1846 this same ship, along with her sister ship Terror and 129 men, vanished off the face of the earth whilst trying to find a way through the Northwest Passage. It was the greatest single loss of life in the history of British polar exploration.

I wrote and delivered my talk on Hooker, but I couldnt get the adventures of