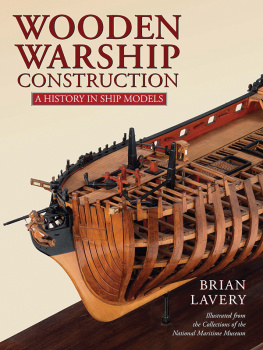

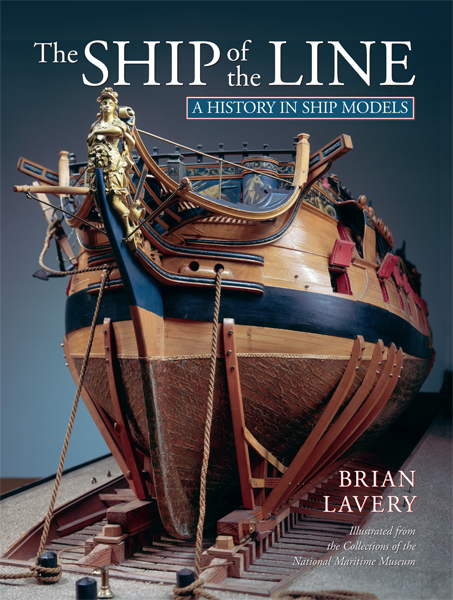

SLR0650 An unidentified

74-gun ship of about 1800.

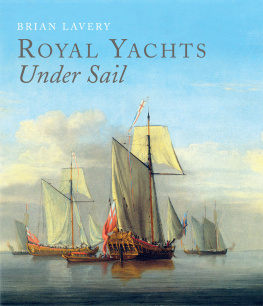

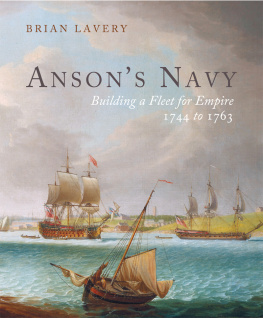

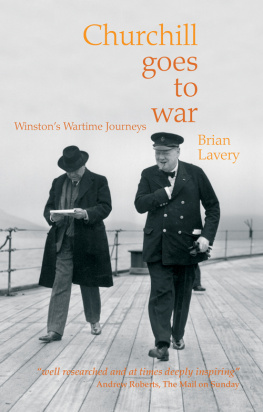

Acknowledgements

The publishers would like to thank the staff of the National Maritime Museums Picture Library, and especially Emma Lefley, who faultlessly organised the complicated issues surrounding the large photo orders. For curatorial help and arranging special photography, we are grateful to Simon Stephens.

Arnold and Henry Kriegstein graciously allowed us to use illustrations of two of the finest models in their family collection, while Major Grant Walker of the US Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis was immensely helpful with both photographs and information on the one-time Sergison collection.

Additional illustrative material came from the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; Magdalene College, Cambridge; and Wilton House.

References

Models in the National Maritime Museum collection are catalogued by SLR number, and in this book these are quoted at the beginning of each caption to one of these models. Further details of these models can be found on the Museums Collections website at:

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections.html#!cbrowse

Searching by SLR number will turn up a full description of the model and any available photographs.

Copyright Brian Lavery 2014

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Seaforth Publishing

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street, Barnsley

S Yorkshire S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

Email info@seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP data record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84832 214 1

eISBN 9781473811669

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Brian Lavery to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Contents

: The Origin of the Ship of the Line

B y definition, a ship of the line was one that was big and powerful enough to stand in the line of battle against anything the enemy could put alongside it, and as a ship is long and narrow, and if it is to carry a heavy armament, most of that armament must be mounted mainly on the broadsides. Therefore gun armament is essential to the whole concept. The idea of disposing ships in a single line when going into battle seems so obvious with our hindsight that one wonders why it was not instigated until ships had carried heavy guns for a century and a half. But it must be remembered that in the early days the heavy gun was not necessarily the main weapon, and at first the broadside was not supreme.

Ships had been fitted with light guns of some kind since the 1460s, but the first generation of real gun-armed warships only came with the invention of the gunport around 1500. That allowed a heavy gun to be mounted low in the ship without raising the centre of gravity, but it could be protected from enemy gunfire and rough seas by closing the ports. This generation is represented most dramatically by the remains of the Mary Rose on display at Portsmouth, and the thirty-year service of the ship tells us much about the growing importance of guns and the tactics associated with them. Her first armament list dates from 1514 when she carried a total of 78 guns, but only 5 of these were heavy. The Mediterranean galley was the first type to deploy great guns effectively armed, mounting heavy basilisks in the bows to fire forward. Though they rarely had ideal conditions to operate in more northern waters, they did make a great impression on the English fleet in 1513. According to Edward Echyngham, 6 galleys and 4 foists came through part of the Kings navy, and they sank the ship that was Master Comptons, and strake through one of the Kings new barks, which Sir Stephen Bull is captain of, in seven places, that they was within the ship had much pain to hold her above the water.

Sailing ships could not hope to match the manoeuvrability of the galley in light winds, but one answer was to fit more heavy guns to defend the ship from any direction, especially from ahead. In 1545 naval officials had resisted Henrys attempt to fit yet more forward-firing guns to the ageing hull of the Mary Rose . Already she had over the luff two whole slings lying quarter-wise, that is, firing forward from the castle in the bows. In addition, there were two culverins at the barbican head or the break of the quarterdeck firing forward past the forecastle, plus two sakers on the deck above. It would not be possible to fit any more forward-firing armament without the taking away of two knees and the spoiling of the clamps that beareth the bitts, which will be a great weakening to the same part of the ship. The guns were apparently not fitted and the Mary Rose sank while engaging French galleys in the Solent, though from accident rather than enemy action.

When she was built in 1509 the guns of the Mary Rose were probably regarded as auxiliary weapons to support boarding, but she had extra ones added, especially in the latter years of her long career which covered three wars. This drawing, by Anthony Antony, the surveyor of the ordnance, is part of a series depicting the whole of Henry VIIIs fleet and is the only known contemporary picture of her. The rigging is not very accurate, with the yards apparently set on the wrong side of the mast and shrouds. The ship is heavily decorated with paint and flags but shows little sign of any carvings. It shows heavy guns pointing from the stern and even across the waist. As it is drawn from astern as was common at the time, it does not show the forward-firing armament installed in the 1540s to give all-round protection against galley attack. The excessive weight of guns was almost certainly a major factor in her loss in 1545.

Magdalene College, Cambridge

The English adopted galleys but were never entirely happy or successful with them. Meanwhile, the Venetians developed the galleass, with the oars of a galley and a castellated superstructure fitted with guns. They had great success against the Turks at Lepanto in 1571, and also led to the Spanish galleon, a ship with good gun armament and sailing qualities. Soon they fell into the temptation of building their ships too high, while the English, under the leadership of Sir John Hawkins, produced the race-built galleon with lower superstructure and better sailing qualities.

This generation is represented by the drawings of Matthew Baker, the leading Elizabethan shipwright. The quarter frame system as represented by the Mary Rose is still in use, as one plan shows the classic five stations: the midships frame, two quarter frames, the stern frame and the curved stempost forward. These could be constructed and then joined by battens on the building slip so that the shapes of the other frames could be found. However, Baker has added rising lines, narrowing lines of the floor and maximum breadth which were used to draw the frames in between, rather than having to rely on battens during the actual construction. Despite the emphasis on speed, Bakers ships tend to have fuller bows than the Mary Rose , for they were intended to carry a heavier armament forward.