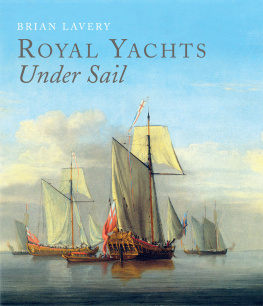

ROYAL YACHTS

Under Sail

ROYAL YACHTS

Under Sail

BRIAN LAVERY

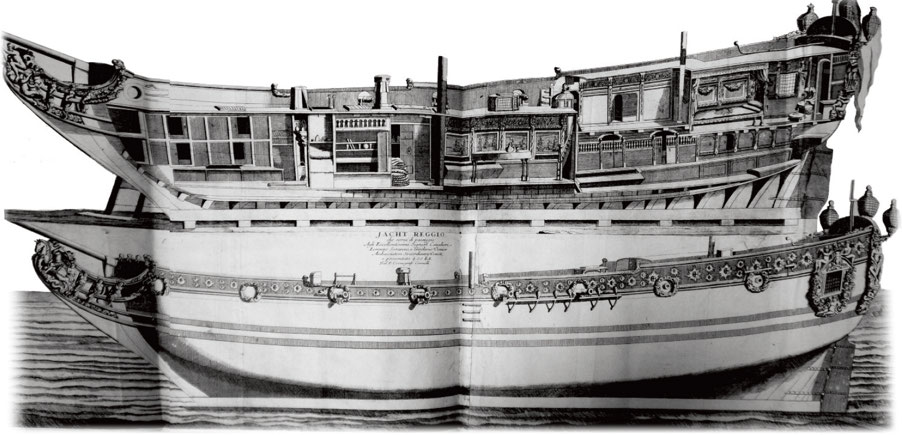

Half title: Vincenzo Coronellis drawing of a royal yacht, from his book Ships and Vessels, Venice 1697. See page 129.

Title page: Detail of a painting by Peter Monamy depicting the arrival of George I in the lower Thames. See page 59. (Richard Green Gallery)

Copyright Brian Lavery 2022

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

Seaforth Publishing,

A division of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 3990 9291 3 (HARDBACK)

ISBN 978 1 3990 9292 0 (EPUB)

ISBN 978 1 3990 9293 7 (KINDLE)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Brian Lavery to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl

Contents

Introduction

My first, very indirect, contact with royal yachts came in the spring of 1953 when the young Queen Elizabeth II was driven past our school on the way to launch the Britannia in Clydebank. More than forty years later I attended one of the last receptions on board her in Portsmouth. The decommissioning of her shortly afterwards remains controversial.

There have been several very good books on royal yachts already, as listed in the bibliography. This one, I hope, probes deeper than before into the design and construction of these vessels, aided by the detailed cataloguing of the Navy Board letters in the Adm 106 in the National Archives, which opens up many possibilities for research, and by a number of recent articles in The Mariners Mirror. I first became interested in the subject after researching a Peter Monamy painting on behalf of the Richard Green Gallery in London. It showed, as it turned out, the arrival of George I in England in 1714, one of several examples of British and French regime change facilitated by the yachts. This led to the recognition that very little had been written about the actual uses of the yachts. Broadly, they served mainly as pleasure craft, diplomatic vehicles, transports of kings and military leaders in peace and war, and occasionally as war vessels in their own right. Steam yachts opened up new possibilities, allowing Queen Victoria to visit the more remote parts of the United Kingdom, and Elizabeth II to have a kind of floating palace as a base during overseas visits.

The original yacht, of Dutch origin and British by adoption, developed in at least two different directions, which is reflected in the double meaning of the word today. It can be a sailing vessel, usually decked and with simple accommodation, used for cruising or racing by people of quite moderate means; or it can be a vastly expensive and luxurious vessel owned by a billionaire, and probably used more as floating accommodation than as a means of getting from A to B.

Their potential uses prompts the recurring question: should a new British royal yacht be built? Clearly the world is very different, not just from 1660 when Charles II first encountered yachts on his ecstatic passage back to England, but from the 1950s when the Britannia was designed and built. Britain no longer has an empire, and the sea is no longer an important means for people to travel long distances, except for leisure or as desperate would-be immigrants. But more important than that, it is difficult to imagine any government paying for a yacht which could match the opulence of those belonging to the plutocrats; a new Britannia would not be guaranteed to enhance British prestige.

Instead, I recommend readers to savour the yachts of history, as represented in models, an exquisite print by Vincenzo Coronelli, and the paintings and drawing of such masters as the Van de Veldes, Sir Godfrey Kneller, Peter Monamy, Dominic and John Thomas Serres, J C Schetky, and Nicolas Pocock; and to relish their fascinating history as revealed by documents and manuscripts of the past.

Brian Lavery, May 2022

Part I

Sailor Kings

The Origin of the Yacht

The idea of a specialised ship for royal transport did not originate until well into the modern age. Medieval English monarchs usually travelled short distances by sea to visit their realms, especially their holdings in France, and initially this was organised on a feudal basis. In 1240 the lord of the manor of Padworth in Berkshire, for example, held the manor in exchange for finding a man to hold a rope in the Queens ship when she crossed from England to Normandy.

Otherwise kings mostly travelled for warlike purposes. For England the medieval era began with William the Conquerors voyage across the English Channel in 1066. He headed a fleet of around seven hundred ships, apparently in a standard open Viking-type longship like many others. According to the Bayeux tapestry it was distinguished by a rectangular structure at the head of the mast, which may have been a beacon, as fire was one of the signals available to him. It was faster than most, however, and at one stage he almost jeopardised the operation by going too far ahead. He attempted to reassure his men by having a plentiful and cheerful meal, as if he was in his own hall, served with spiced wine, suggesting that he had at least some facilities on board.

The longest voyage by a medieval English king was Richard Is crusade to the Holy Land in 1190. He joined his fleet at Marseilles, leaving his ally Philip Augustus of France, who suffered from seasickness, to travel by land through Italy. Richard settled in a galley which was one of a group sailing a fleet of more than a hundred ships, with a small household, and the chief men of the army, with his attendants. We know no more about his accommodation on board, but as in most royal voyages there was as much show and pageantry as possible: So great was the splendour of the approaching armament, such the clashing and brilliancy of their arms, so noble the sound of the trumpets and clarions.

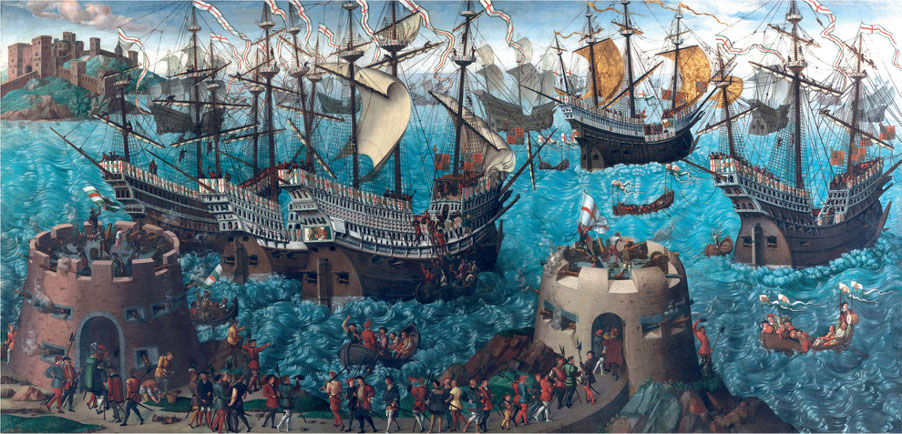

Henry VIII sets out from Dover for the Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1620. His bulky form can just be seen on the ship with golden sails in the distance to the right. (Royal Collection Trust / Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022, 405793)