ABOUT THE AUTHOR

MICHAEL HALL is the editor of art-history periodical The Burlington Magazine. He has published several books on 19th-century art, architectural history and the history of collecting, and has recently completed a history of the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore, to be published by the Royal Collection.

ABOUT THE BOOK

The largest private art collection in the world, the Royal Collection contains over a million artworks, from world-famous paintings by masters such as Rembrandt and Holbein to exquisite Faberg eggs and sculptural masterpieces. An unparalleled cultural treasure, the Collection also charts a unique history of the British monarchy over the past 500 years.

The first official history of the Royal Collection, this lavishly illustrated book traces its development from the Middle Ages to the present day, offering a revealing insight into the tastes and obsessions of British kings and queens through the centuries. Accompanying a major BBC series and with a foreword by HRH The Prince of Wales, Art, Passion & Power sheds new light on the enduring relationship between art and the monarchy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Jonathan Marsden, Director, Royal Collection Trust and Surveyor of the Queens Works of Art, and Jemima Rellie, Director of Content and Audiences, for suggesting that I write this book, and Albert DePetrillo, Publishing Director at BBC Books, for giving me the opportunity. Jonathan read the text in draft and greatly improved it. I am indebted to Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Surveyor of the Queens Pictures, and Rufus Bird, Deputy Surveyor of the Queens Works of Art, for discussing the collection with me, answering queries, and giving me access to works on display and in conservation. The Librarian, Oliver Urquhart Irvine, introduced me to the Royal Library, where I was guided by Elizabeth Clark, Curator of Books and Manuscripts. Kate Heard, Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings, showed me works in the Print Room. It was a pleasure to tour the palaces on research trips with Sebastian Barfield, director of the BBC series that this book accompanies, and I learned a great deal from discussions with him about the collection and the monarchs who made it. I am grateful also to Steven Brindle for kindly allowing me to read a typescript of the definitive history of Windsor Castle that he has edited, which will be published by Royal Collection Trust in 2018. I would also like to thank Jacky Colliss Harvey and David Tibbs in Royal Collection Trusts publishing section for their help. Finally, I am most grateful to my editor at BBC Books, Bethany Wright, the copy-editor, Anjali Bulley, and the designer, Linda Lundin, for their patience and encouragement at every stage of a very tight schedule.

Chapter 1

MAGNIFICENCE

From the Middle Ages to Elizabeth I

Only three years after his victory at Hastings, William the Conquerors grasp on his new kingdom appeared to be failing. In the summer of 1069 Danish troops landed on the north coast, where they were joined by a large force of English rebels. William forced his army through to York, where he spent Christmas. From there he sent messengers south to fetch not arms, or more men, but his crown. Christmas was one of the three annual occasions the others being Easter and Whitsun at which the King of England appeared ceremonially at court, wearing his crown. This tradition, which went back to Charlemagne, and before him to the emperors of Byzantium, had been established in England in Saxon times. The Conqueror, eager to proclaim his legitimate claim to the throne, was punctilious in his observance of this ancient assertion of regal identity. It was far from surprising, therefore, that in the midst of war, and in a city that had been sacked by the Danes, William should care about his crown. His respect for royal ceremony was an important aspect of his campaign by persuasion, as well as by force to be accepted by the English as their king. He succeeded: the Danish army sued for peace, and William brutally suppressed all opposition in the north of England.

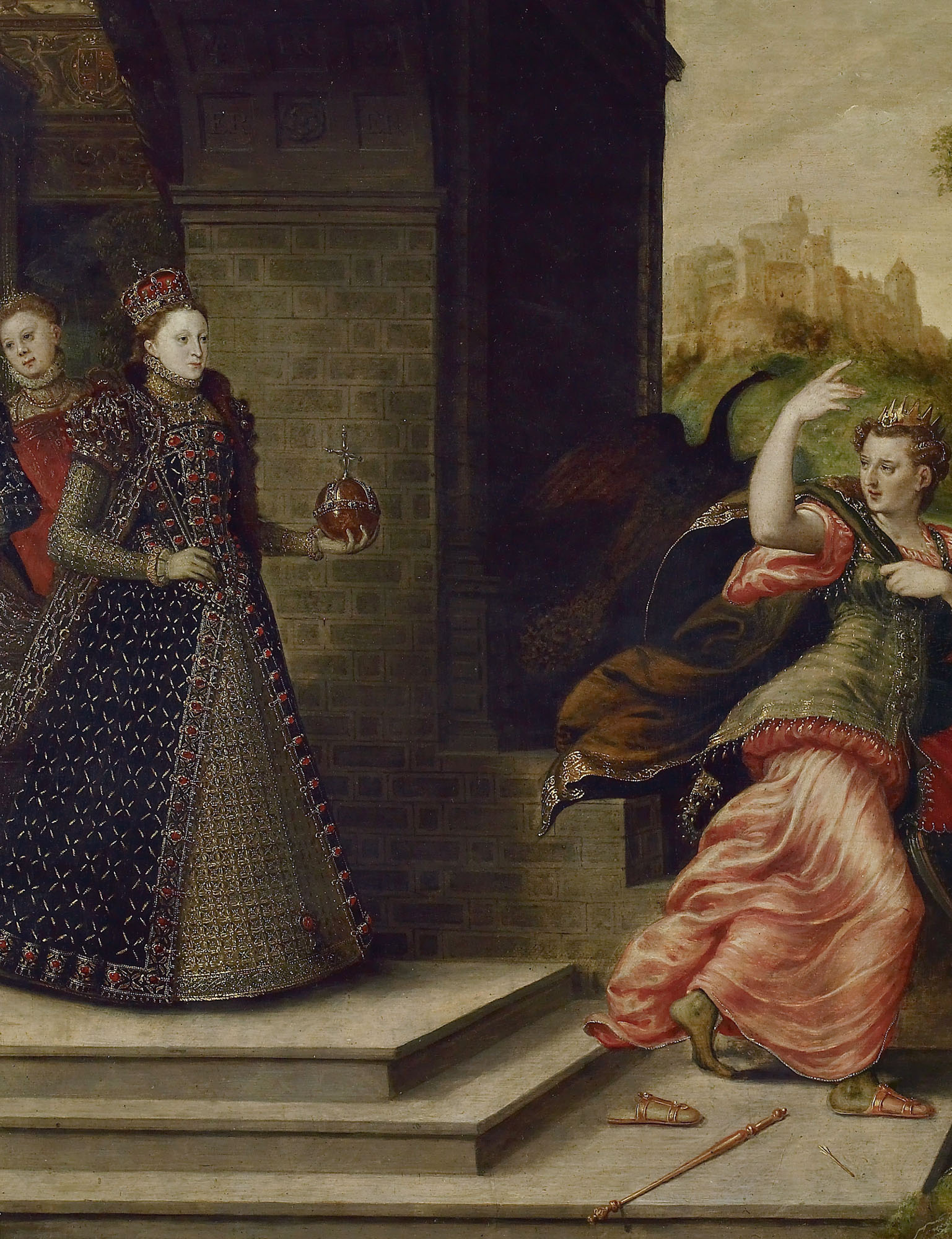

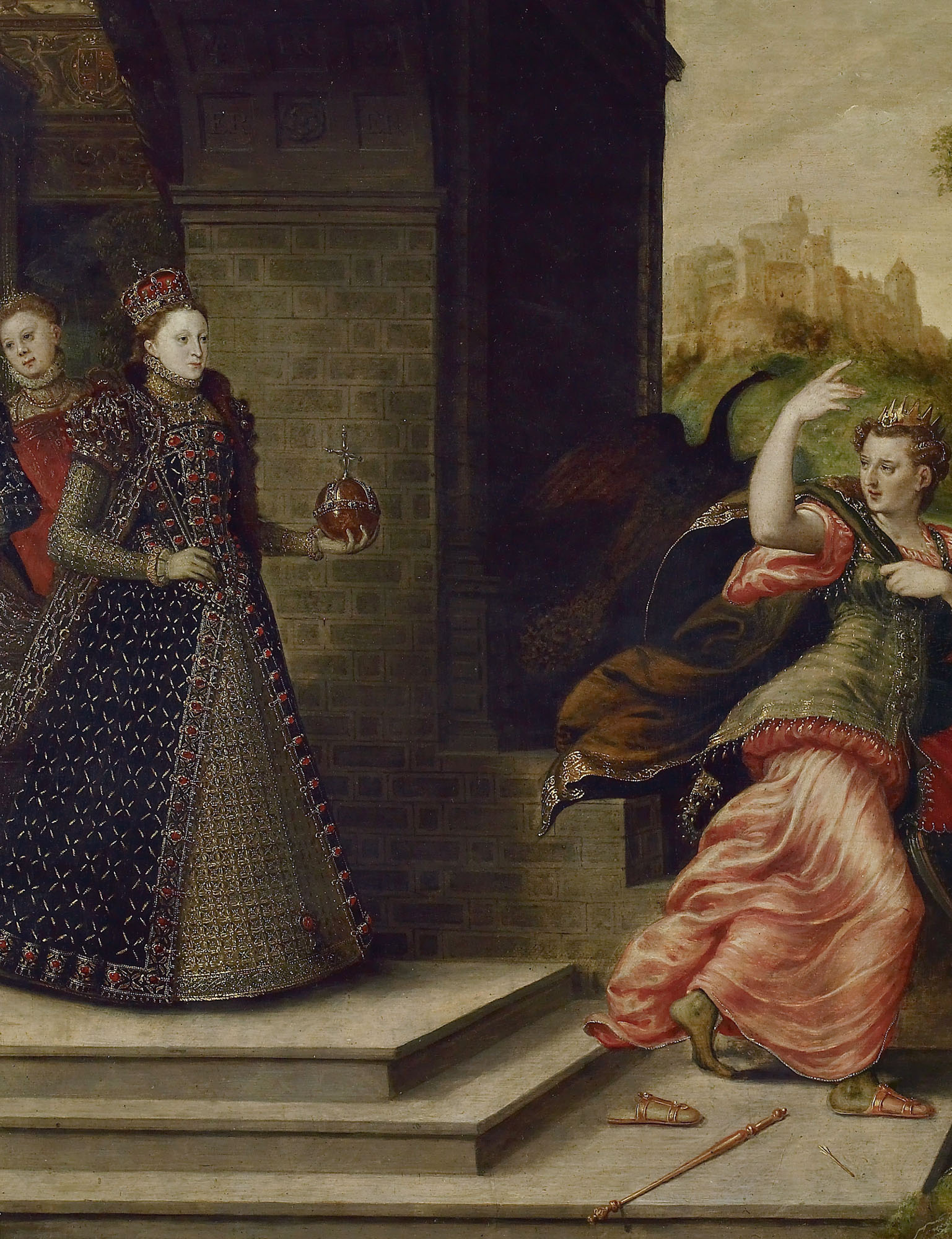

Throughout the centuries that followed, all monarchs understood that it was not enough to be a ruler they had to look like one. An essential attribute of their public standing and authority was magnificence, or the visual expression of wealth and power. On one occasion, neglect of this imperative may have contributed to the loss of a kingdom. In the civil strife that has come to be known as the Wars of the Roses, Henry VI (142171), head of the house of Lancaster, was usurped in 1461 by Edward, Duke of York, who became Edward IV (144283). In 1470, shifting aristocratic allegiances led to Henry being restored, forcing Edward to flee to Burgundy, from where he returned a year later with an army. Henrys allies tried to rally support for him by taking him in procession through the streets of London. However, because it was Maundy Thursday, Henry was dressed in a long blew goune of velvet, an appropriately plain garment for a solemn day. That point was lost on the crowds, who thought he no longer had royal dress, which would have been gold, crimson and ermine. One supporter of Edward IV wrote that the procession was more lyker a play than the shewing of a prynce to wynne mennys hertys.

Edwards army entered London unopposed, and he confirmed his victory by having Henry murdered. Edward didnt make his predecessors mistake when it came to his appearance. Following the state opening of his first parliament after his return to the throne, Edward went in procession, wearing his crown, to Westminster Abbey. There he made offerings at the shrine of his namesake, Edward the Confessor, Englands royal saint, whose feast day it was. Regal piety and liberality were combined with magnificence as a way of announcing that the new dynasty was here to stay.

Attributes of monarchy: the regalia

Any account of the Royal Collection should begin with the crown. It forms part of the regalia, or Crown Jewels, which are the fundamental physical attributes of monarchy. They are made of precious metals and jewels to symbolise the belief that the monarch is not only the supreme source of political authority but is also divinely consecrated by anointment at the coronation, on the biblical model of King Solomon, who was annointed by Zadok and Nathan, as Handels coronation anthem Zadok the Priest reminds us. By extension, therefore, royal identity is embodied in objects of splendour appropriate to a monarchs sacred status: not just gold and jewels, but also magnificent apparel, imposing buildings and splendid possessions the origins of the Royal Collection.

Although the regalia are most closely associated with coronations, the ceremonies enacted by William the Conqueror at York in 1069 and Edward IV at Westminster in 1472 demonstrate the stress that was placed on all displays of these signifiers of royal authority. There had been one important change in the four centuries between those two events. The crown and other regalia were kept at Westminster Abbey, the setting for every coronation since 1066. The abbey church had been built for Edward the Confessor (100366), who was buried there. In 1161 Edward was canonised, which meant that his tomb became a shrine and all objects associated with him were now religious relics. According to the monks of Westminster, the crown had been Edwards, and was, therefore, too sacred to be worn except for coronations. As a result, monarchs commissioned another crown for their ceremonial appearances, known as the great crown. This arrangement, which survived the Reformation and consequent dismantling of the Confessors shrine and discarding of his relics has continued to the present day. Elizabeth II was crowned in 1953 with St Edwards Crown, but has not worn it since. When she appears in state, most regularly for the opening of parliaments (in a tradition well established by the late Middle Ages), she wears the Imperial State Crown, made for her father, George VI, the great crown of modern times ().