Contents

: 1838

1838

Everyone said they had never seen London so crowded. On the day before Queen Victorias coronation it was not just a case of a mob here or there, but a mob seething everywhere; jostling, staring, marvelling aloud at everything and nothing. Flags flew from makeshift poles on roofs, out of windows and above a vast encampment of tents in Hyde Park, where a firework display was planned for the following night, followed by a grand fair. The fashionable world, while just as excited as everyone else and determined not miss a single opportunity for showing off its jewels and robes of state, pretended that so much uproar was uncommonly tiresome, but the queen was not so hypocritical.

Nineteen-year-old Victoria was enjoying every moment of this most glittering of seasons. She had already attended three State balls, two leves, a drawing-room and a State concert, and only regretted that she had not been able to waltz, since there was no one whose arm was considered fit to encircle the royal waist. This in spite of guest lists being ruthlessly scoured for any scent of trade, which, among others, led to the Rothschilds being excluded. Now the time for her coronation had come.

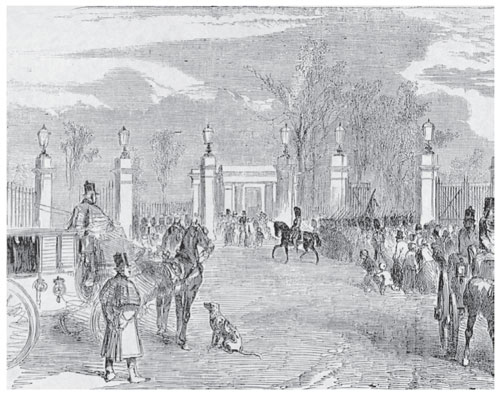

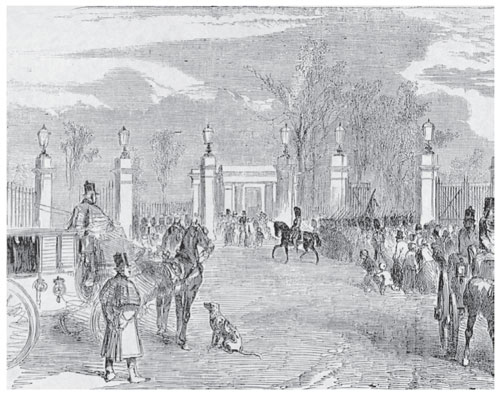

Next day, Victoria woke early, when guns in the park fired salutes at four oclock in the morning. Unable to get to sleep again for the bustle and blare of soldiers and military bands marching past, she was soon peeping at the crowds from behind her bedroom curtains. No previous sovereign had ever looked out on this scene. In 1838 Buckingham Palace was new, the landscaping in St Jamess Park was new, the ceremonial arch outside the palace was new. Only at the last moment had someone thought to try whether the State coach would fit through its centre span, only to discover that it stuck ignominiously. There had not been time to demolish the offending object out of sight, although a pitch would eventually be found for it at the end of Oxford Street, where, with its name changed to Marble Arch, it continued its career of impeding the traffic for no particular reason; a monument to the fact that even eminent architects make silly mistakes.

The coronation route was also new, a roundabout way decided on by the cabinet in the hope that it would be to their political advantage if the young queen was seen by as many of her subjects as possible. Perhaps no institution is quite so finely tuned to public sentiment as an unpopular government, and Lord Melbournes administration had seized gratefully on the chance to gain badly needed credit from a great national occasion. Generous sums were voted to make this coronation unusually splendid, squabbles over the scandalously insanitary condition of the queens recently completed palace forgotten, and matched cream horses solicited as a gift from Hanover to draw her gold State coach, since Lord Melbourne declared that anything less would look like rats in harness.

But contradictions still abounded and the day started badly for the aristocracy, who rose before dawn to dress in antique finery only to find Westminster Abbey still locked and dark. A growing throng of irascible nobility shivered in a drizzling wind for nearly an hour before the keys were found. A good few hip-flasks were probably swigged to keep out the cold and a picnic atmosphere soon developed inside the abbey, from which the decorum of the day never quite recovered. These were people whom inter-marriage had interlocked for generations and to them, coronations were tribal occasions.

Those who had endured the earlier rigours of the day made their own entertainment out of the later, official arrivals; clapping and shouting if a country or its representative was popular, preserving a daunting silence if not. When Prince Esterhazy appeared he was dressed in such oriental splendour he was said to look as if he had been caught in a shower of diamonds, while old Marshal Soult, special envoy from France and veteran of Napoleons wars, was overcome by the cheers which followed him down the aisle, and burst into tears.

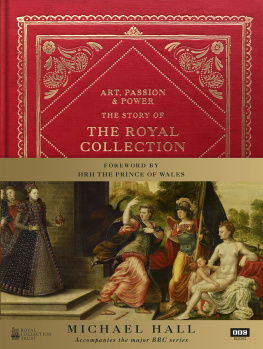

Life around the Court became much more ceremonial during Victorias reign, and the surroundings of Buckingham Palace were improved to provide a backdrop to her empire. ( Illustrated London News , 1856)

As the morning wore on, wind and rain gave way to bright sunshine. Queens weather these lucky changes would come to be called, because Victoria so often enjoyed them in the future, and the onlookers thronging the processional route revelled in it. The crowds of people exceeded anything I have ever seen, Victoria wrote afterwards. Their good humour and loyalty was beyond everything, and I really cannot say how proud I am to be Queen of such a nation .

She was as gay as a lark, one observer commented, laughing like a girl on her birthday as she drove past him. Some of her entourage felt that a properly bred queen should not enjoy herself quite so obviously on a day of sacramental significance, and there were other ruffled sensibilities too. The Duke of Albemarle, for instance, had claimed the right as Master of the Horse to sit beside her on that triumphal drive, and was still smarting from a crushing snub administered by the Duke of Wellington. He had roundly told Albemarle to do as he was told, since the queen could if she pleased make him run behind her coach like a tinkers dog. This, for a constitutional monarch, was certainly untrue and not language a fellow duke readily accepted.

But however sulky Albemarle felt, the crowds remained good-natured, enthusiastic and orderly, though it was less than five years since the previous king, William IV, had leaned out of his carriage to spit at a crowd which failed to cheer him. Victorias youth and her feminity were both the cause of and served to underline this change in feeling. We have got a shabby kind of family to rule over us, Boswell had once remarked about the Hanoverians, and now quite visibly it was shabby no longer. Victoria on her coronation day was resplendent, joyful, girlishly innocent; a new age seemed to ride beside her in the golden coach.

Once she reached the abbey she became dignified and solemn, the scene sufficiently spectacular to make even a queen falter for a moment. The old grey building blazed with colour; from banners, clothes, and carpets. Stars glittered from precious plate on the altar and the copes worn by the bishops had been embroidered for the coronation of James I more than two hundred years before.

As she moved down the aisle, the sun struck through the windows high above Victorias head to play with extraordinary effect on the quantities of jewellery worn by the packed congregation, splitting light into prisms and rainbows which broke like spray as the lines of people turned to bow and curtsy as she passed. The men wore more exotic colours than the women: scarlet, blue and gold for the military and crimson for the peers, while representatives from the Empire and the world appeared in every shade imaginable, studded by precious stones as large as eggs.

If the queen briefly trembled at such a sight, the effect she produced on a sceptical and hardened audience was astonishing. Her diminutive size and instinctive poise, when surrounded by such a vastness of worldly pomp, seemed to overwhelm them all. Attended by ten unmarried girls as trainbearers, she seemed to float down the aisle towards the altar in an ethereal, shining cloud. Everyone gasped for breath, wrote one onlooker. The rails of the gallery where I sat trembled from the grasp of a hundred trembling hands. I never saw anything like it. Tears would have been a relief.

Next page