Private and Royal Life in

the Ottoman Palace

lber Ortayl

Copyright 2013 by Blue Dome Press

17 16 15 14 / 1 2 3 4

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Published by Blue Dome Press

535 Fifth Avenue, Ste.601

New York, NY 10017-8019

www.bluedomepress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

Epub

Ahmet Kahramanoglu

DIJITAL ISBN: 978-1-935295-35-8

Printed by

alayan A.., Izmir - Turkey

Introduction

T opkap Palace attracts more visitors than any other place in Turkey. Once the heart of Ottoman administration and the residence of the sultans, the elegantly decorated palace is surprisingly modest. In this work, Dr. Ortayl introduces us to the different sections in the palace, providing us with information about their functions, architecture and decorations. His references to the palace customs, people, and particular events present us with a living history.

This work has much to offer even for those who have had a chance to visit the palace. Ortayls explanations reveal his expertise in the field and certain misconceptions about the Ottomans are corrected. Moreover, this book covers some of the closed sections as well. For example, certain parts of the Harem are completely built of wood and therefore, visitors are not allowed as a precaution against possible damage. Some of these places have been photographed for the first time.

In the name of our company and our readers we would like to express our thanks to everyone who was part of the team in the production of this book: Dr. lber Ortayl, the head of the museum and the author of this work, the former manager of the museum, Nurullah akr, the assistant manager Glendam Nakipolu, the chief of museum security Mehmet Aydn, Dr. Ortayls assistant Selin pek, the other section experts, curators and all the staff.

Blue Dome Press

Preface

T opkap Palace was the residence of the Ottoman sultans. It was built on the orders of Mehmed the Conqueror in 1460, and some additions were made in later periods. Ottoman sultans and members of the court lived here until the mid-nineteenth century. The palace did not suffice for the state protocol and ceremonies of the nineteenth century and Sultan Abdlmecid, son of Mahmud II, did not stay much in Topkap from the 1830s on. At the beginning of the 1850s, the Ottoman sultans moved permanently to Dolmabahe Palace on the Bosphorus. However, the treasury, the Sacred Trusts, and the imperial archives were still preserved in Topkap.

Two years after the Ottoman monarchy was abolished in 1922, Topkap became a museum. The 12,000 pieces of Chinese and 900 pieces of Japanese porcelain constitute a particularly significant collection in the museum today. In addition, unique collections of Turkish clothing from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, carpets, weaponry, and European porcelain constitute rich displays in the museum. The museums library of manuscripts contains more than 18,000 original books; these are not only in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, but also in Slavic languages, in Greek, Armenian, Latin, and Hungarian. The section where Mehmed the Conqueror, the founder of the palace, previously lived has now been converted into the treasury. The treasury contains a gift throne from Iran, which is next to the Ottoman throne, various gifts from the Indian Babur period, a holy relic from the Byzantium, countless jewels, and rare pieces such as the famous Kak Diamond.

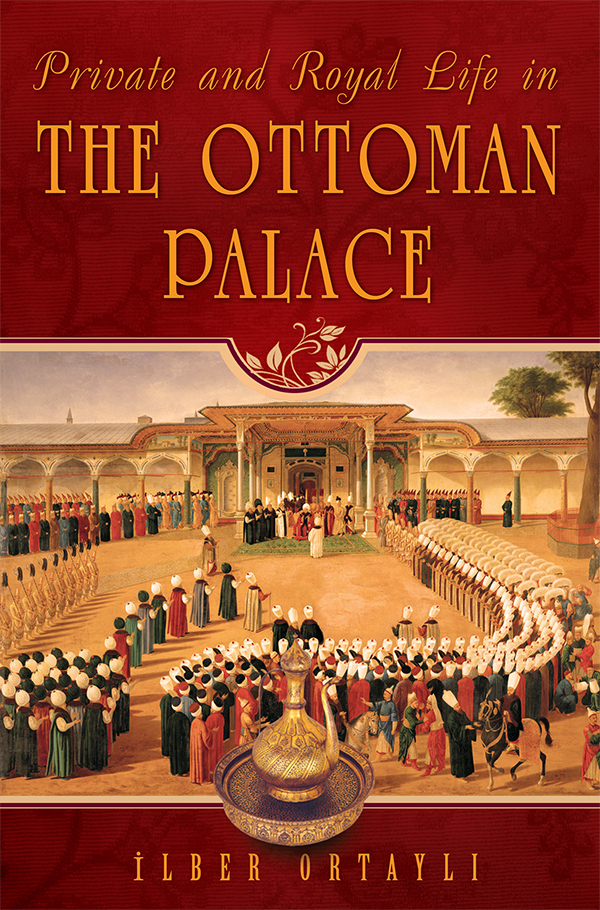

The kitchens are one of the most interesting sections of the Ottoman palace. Some royal carriages are exhibited today in a part of this section. The highest point in the palace is the Tower of Justice, which is next to the Imperial Council Hall. The middle courtyard near this structure was the place where the Janissaries received their three monthly payments in a great ceremony, often observed by foreign envoys.

The inner palace, comprising the Harem and Enderun, which is considered the abode of the sultan, played a significant role in the course of history. The Enderun is the section where selected recruits were trained for the administration of the state and commanding of the army. They received lessons in theory and also served at the palace; those who served thus knew how to make services run smoothly. A young recruit coming to the palace might leave the palace after some fifteen to twenty years as a general. Strict discipline prevailed in the Enderun Courtyard and dormitories. Today, visitors favorites, such as the clothing display, the Imperial Treasury, and the Sacred Trusts are in the chambers around this courtyard. The belongings of the Prophet and other holy figures are visited in the Pavilion of the Sacred Trusts or Apartments of the Holy Mantle by people of all faiths.

The Harem was the section where girls and young women taken captive in war or purchased as slaves were educated. Not all of these young women, who were taught how to read and write, dress elegantly, play and compose music, and follow the court etiquette, were intended to be consorts of the sultan. Other high-ranking statesmen also married girls educated in the Harem. For instance, in almost all the neighborhoods of the foremost cities such as Istanbul and Bursa, there would be a woman who had been educated at the palace before marrying a prominent figure from that area. This was the way palace etiquette spread through society.

One of the most important sections of the Ottoman palace is the archives. Almost all the documents about the Ottomans and those about all the sovereign states the Ottomans had relations with can be found here. World history cannot be written accurately without studying these archives.

Topkap Palace is modest; more significant expenditure in the empire was dedicated to building magnificent mosques, military barracks, bridges, caravanserais, and hostelry facilities for merchants and travelers. Even Sinan, the famous architect of the sixteenth century, only built a single section in the palace. However, wherever it is viewed from, the beautiful pendant-shaped structures of the palace, its glorious tiles, and its lovely setting, which embraces nature, look grand; this is natural splendor. The hundreds of servants and several thousand cavalrymen (six troops) inside led a simple life free from lavishness.

The fabrics in the museum are the best works of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and delicious dishes of Turkish cuisine were prepared in the kitchens. Nevertheless, although the residents had their meals on Chinese porcelain, they lived a modest, disciplined and programmed life in narrow rooms. Even the majesty of the sultan was meant for the outside rather than the inside, for the people would not be fond of a plainly dressed sultan. The ceremonies of the Ottoman palace were spectacular; impressive to foreign guests and Ottoman people. Every week, the sultan emerged from the palace in a magnificent procession to attend Friday prayer in one of the mosques of the city. The petitions presented to the sultan in the palace were in the various languages of the peoples of the Ottoman lands.

At the princes circumcision ceremonies the palace treated the people generously; several ceremonies and shows would be held. The processions by the guilds were significant. When the army returned home after a victory, a grand parade of proud soldiers with their arms and uniforms would pass through the city.