SHIP SPOTTERS GUIDE

SHIP SPOTTERS GUIDE

Compiled by Angus Konstam

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

W arships have existed almost as long as mankind has plied the seas. The first recorded warships date from more than 3,000 years ago, and while their appearance has changed markedly, the role of these ships has largely remained unchanged. In their simplest and oldest role, warships exist to protect the sea lanes, and to safeguard friendly ships. How this is achieved can vary enormously. In the Ancient World, it meant keeping the seas free of pirates and maintaining a fleet to counter an attack by enemy squadrons. In the great Age of Fighting Sail warships had become more specialized, and so the job of protecting the sea lanes was carried out by smaller warships, while the larger ones the ships-of-the-line stood ready to fight the enemy for control of the seas.

The advent of steam and steel did little to alter this basic role, or change the division of functions. If anything, warships became even more divided by form and function. In theory the advent of the ironclad rendered all existing warships obsolete, but wooden-hulled ships still had a role to play as commerce raiders or as patrol vessels, gunboats or pirate hunters. The next great revolution came in 1905, with the launch of HMS Dreadnought. For the second time in half a century existing warships were rendered obsolete, and so a new arms race began one that arguably was instrumental in the increase of diplomatic tension that led to the outbreak of World War I.

In that war to end all wars, the great fleets of dreadnoughts faced each other across the North Sea, while other smaller ships established the blockade of Germany and cleared the sea lanes of German shipping. Ultimately the great clash of dreadnoughts at Jutland in 1916 did less to bring about the end of the war than the hardships created by the Allied blockade. The German response was to launch their U-boats against Allied shipping. This led to a new kind of warfare or rather a more modern version of the commerce raiding and privateering of previous centuries. The war also saw the emergence of naval airpower and the creation of the first aircraft carriers.

By 1942 it was clear that aircraft carriers rather than battleships were now the arbiters of victory at sea. Submarines too had a greater role in World War II than in the previous global conflict, although they also demonstrated their vulnerability to new forms of anti-submarine warfare.

Since the end of World War II, submarines and aircraft carriers have continued to reign supreme. While the end of the Cold War removed the need for large fleets of nuclear submarines, the new breed of super carriers and cruise-missile armed surface ships and submarines have seen the old limits of sea power removed. Now, thanks to modern weaponry, naval task forces can make their presence felt thousands of miles from the sea. This more than anything demonstrates that warships are as useful today as they have ever been. Just as they have for centuries, warships protect maritime trade, and serve as a counterpoint to enemy naval aggression. The difference, though, is that todays warships have a global reach, and possess a degree of destructive potential unmatched in 3,000 years of naval history.

Angus Konstam

Orkney, 2014

ANCIENT WARSHIPS

M ankinds long association with the sea began in the Neolithic period, around 12,000 years ago the earliest date archaeologists have found evidence of maritime trade. However, the earliest known images of boats came much later, around 5,500 years ago, when crude vessels were first depicted in rock carvings and pottery found in the valley of the River Nile and in Greece. One of these Greek craft, dated around 3500 BC, possibly contains the first depiction of a warship and a naval battle. It shows a light oared vessel with an archer on its deck.

By around 2000 BC pictorial images of boats become more commonplace, but it was not until about 1200 BC that we first see the depiction of craft that are indisputably warships. These date from the reign of Pharaoh Ramses III (reigned 11861155 BC), and show slender-oared galleys, fitted with a single mast and sail. Images of these ships taking part in a great naval battle commemorate the pharaohs victory over the Sea Peoples in c.1175 BC.

In the Aegean at around the same time, similar oared vessels appear on vase fragments and as votive models, and by the 8th century BC depictions of far more powerful Assyrian vessels appear biremes, powered by two banks of oars. By the 6th century BC biremes are frequently depicted in Greek art, but by the end of the century they begin to be replaced by even larger triremes, with three overlapped oar banks. These evolved into the classic Greek trireme the warships that triumphed over the Persians at the Battle of Salamis (480 BC) and which fought in the Peloponnesian War. By the 4th century BC four- and five-banked quadriremes and quinquiremes appear, and these became the primary warships in use during the First Punic War, fought between Carthage and Republican Rome. Roman naval supremacy in the Mediterranean basin rendered these great lumbering warships unnecessary, which led to a return to lighter but faster biremes, ideal for hunting down pirates. These remained in use until after the fall of the Roman Empire.

Egyptian War Galley

Ship details

This warship is based on the relief of Ramses III at Medinet Habu c.1175 BC. These ships were probably the pride of the Egyptian Navy and at the cutting edge of current technology. Though they bear similarities with earlier Egyptian vessels, the rigging, loose-footed sail, transverse beams strengthening the hull and simplified bow and stern decorations make them similar to those of other Mediterranean cultures.

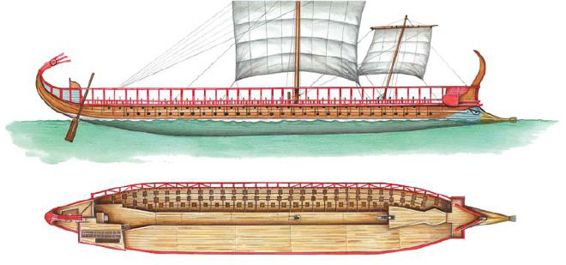

Athenian Trireme

Ship details

This artwork depicts an Athenian trireme. The fundamental innovation of a 5th century BC trireme was that the oarsmen were not arranged in straight lines, but in three staggered banks. This arrangement meant that the rowers didnt hamper each other, and there was no need for a high freeboard or an exceptionally long vessel.

SPECIFICATIONS: ATHENIAN TRIREME

Length: 36.80m (120ft)

Beam (hull): 3.65m (12ft)

Beam (outriggers): 5.45m (18ft)

Draught: 1.20m (4ft)

Displacement: 41.3 tons

Crew total: 200

Oarsmen: 170

62 upper oarsmen

54 middle oarsmen

54 lower oarsmen

Armed men: 14

10 citizen marines

4 mercenary archers

Specialist seamen: 16

1 sea captain

1 helmsman

1 bosun

1 bow officer

1 shipwright

1 double-pipe player

10 deck hands

THE NORSE LONGSHIP

T he earliest representation of Scandinavian ships date from the late Stone Age, around 2000 BC, while the first surviving vessel is the Hjortspring boat, built around 200 BC. This was a simple wooden dugout with built-up plank sides, which has been seen as the forerunner of the more developed Nydam and Kvalsund boats, whose remains date to the 4th and 7th centuries respectively. The style of the two is similar, but the latter vessel was designed to carry a mast and sail.