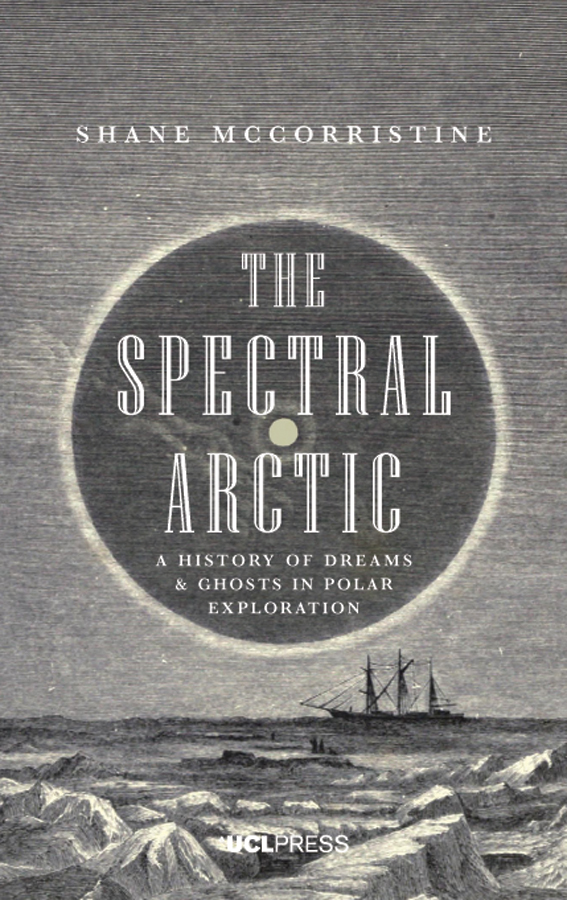

The Spectral Arctic

The Spectral Arctic

A History of Dreams and Ghosts in Polar Exploration

Shane McCorristine

First published in 2018 by

UCL Press

University College London

Gower Street

London WC1E 6BT

Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ucl-press

Text Shane McCorristine, 2018

Images Copyright holders named in captions, 2018

Shane McCorristine has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library.

This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information:

McCorristine, S. 2018. The Spectral Arctic: A History of Dreams and Ghosts in Polar Exploration. London: UCL Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787352452

Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/

ISBN: 9781787352476 (Hbk.)

ISBN: 9781787352469 (Pbk.)

ISBN: 9781787352452 (PDF)

ISBN: 9781787352483 (epub)

ISBN: 9781787352490 (mobi)

ISBN: 9781787352506 (html)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787352452

Epigraphs

There can be no question that in the frozen wastes and snowy wildernesses lurks a powerful fascination, which proves almost irresistible to the adventurous spirit. He who has once entered the Arctic World, however great his sufferings, is restless until he returns to it. Whether the spell lies in the weird magnificence of the scenery, in the splendours of the heavens, in the mystery which still hovers over those far-off seas of ice and remote bays, or in the excitement of a continual struggle with the forces of Nature, or whether all these influences are at work, we cannot stop to inquire. But it seems to us certain that the Arctic World has a romance and an attraction about it, which are far more powerful over the minds of men than the rich glowing lands of the Tropics (Adams, 1876, iii).

NOT HERE! THE WHITE NORTH HAS THY BONES; AND THOU

HEROIC SAILOR-SOUL

ART PASSING ON THINE HAPPIER VOYAGE NOW

TOWARD NO EARTHLY POLE

(Tennysons epitaph to Franklin, Westminster Abbey)

They were walking inland, walking the mainland the nunamariq the real land. They were a raggedy bunch and their clothing was not well made. Their skins were black and the meat above their teeth was gone; their eyes were gaunt. Were they tuurngait spirits or what? (Towtongie qtd. in Eber 2008, xi).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Michael Bravo for his guidance, input and friendship throughout this project; to Chris Morash for his support in Ireland; to Heather Lane, Naomi Boneham, Lucy Martin, Naomi Chapman, Kate Gilbert, Rosie Amos, Julian Dowdeswell, Bryan Lintott and the entire staff of the Scott Polar Research Institute for providing a supportive and scholarly home in Cambridge for many years; to Claire Warrior at the National Maritime Museum for her kind assistance; to Janice Cavell, Russell Potter and my anonymous reviewers for sharing their knowledge and expertise with me; to Chris Penfold at UCL Press, who was a pleasure to work with; and to my wife and family.

This research was undertaken while I was a scholar at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society (LMU Munich), Maynooth University and the Scott Polar Research Institute. This book was made possible by an Irish Research Council CARA Marie Curie Fellowship, for which I am immensely grateful.

Sections of ); and Searching for Franklin: A Contemporary Canadian Ghost Story, in British Journal of Canadian Studies, 26:1 (2013) (reprinted with the permission of the Licensor through PLSclear).

Contents

List of illustrations

Introduction

Arctic dreams

In 1893, while frozen in the Arctic ice aboard his expedition ship the Fram, the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen reflected on the environment around him:

Nothing more wonderfully beautiful can exist than the Arctic night. It is dreamland painted in the imaginations most delicate tints; it is colour etherealised. One shade melts into the other, so that you cannot tell where one shade ends and the other begins, and yet they are all there. No forms it is all faint, dreamy colour music, a far-away, long-drawn-out melody on muted strings (Nansen, 1897).

In popular myth Nansen is the archetypal Scandinavian polar explorer a manly, no-nonsense hero with little time for the sentimentality or plodding amateurism of his British contemporaries. However, Nansens account of this expedition, Farthest North (1897), reveals someone with a deeply romantic outlook whose musings on the Arctic dreamland have much in common with the thoughts and ruminations of other nineteenth-century polar explorers. Nansens was a book, moreover, that did not just appeal to other explorers, for it was massively popular too, selling some 40,000 copies shortly after its publication in English (Huntford, 1997, 442).

Some years later in a busy household in Vienna, the psychiatrist Sigmund Freud read the German translation of Farthest North after noting that his family were hero-worshipping Nansen: Martha [Freuds wife] because the Scandinavians obviously fulfil a youthful ideal of hers, which she has not realized in life, and Mathilde [Freuds daughter] because she is transferring her allegiance from the Greek heroes she has hitherto been so full of to the Vikings. Freud was in the midst of writing The Interpretation of Dreams when he read Nansen, and had recently begun an intense period of self-analysis. It was in this context that he thought he could make use of the practically transparent polar dreams that Nansen wrote down (qtd. in Lehmann, 1966, 388).

Although they never met, Freud and Nansen shared more than an appreciation for dreams. Like Freud, Nansen was an early investigator in neuroanatomy and in his doctoral dissertation on the central nervous system defended in 1888 Nansen cited and challenged some of Freuds ideas. While Nansen soon after launched a successful expedition to cross Greenland on skis, Freud was forced to shelve his neuroscientific research and earn a living as a specialist in private practice. As a psychologist he was fascinated by the motivations of polar explorers and was impressed by their heroic feats; but in the case of Nansen a rival neuroanatomist who became internationally famous only a few months after graduating his feelings were notably ambivalent (Anthi, 2016).

After reading Farthest North Freud described Nansens mental state as typical of someone who is trying to do something new which makes calls on his confidence and probably discovers something new by a false route and finds that it is not so big as he expected (qtd. in Lehmann, 1966, 388). On a conscious level Freud identified with the polar explorer as a fellow pioneer and intellectual adventurer someone whose theories about reaching the North Pole by drifting with the Arctic ice had been originally dismissed by incredulous scientific authorities in Britain. On an unconscious level, however, Freud conflated his own doubts about discovering something new with Nansens daring voyage into the unknown. In a materialisation of these feelings, Freud himself dreamt of being in a field of ice with Nansen and giving the gallant explorer galvanic treatment for an attack of sciatica from which he was suffering. During this self-analysis Freud realised he had recovered a childhood memory of confusing