William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2018

Text Richard Sale, 2018

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

Photographs Richard Sale and Per Michelsen, 2018 and photographers credited in the Picture Credits

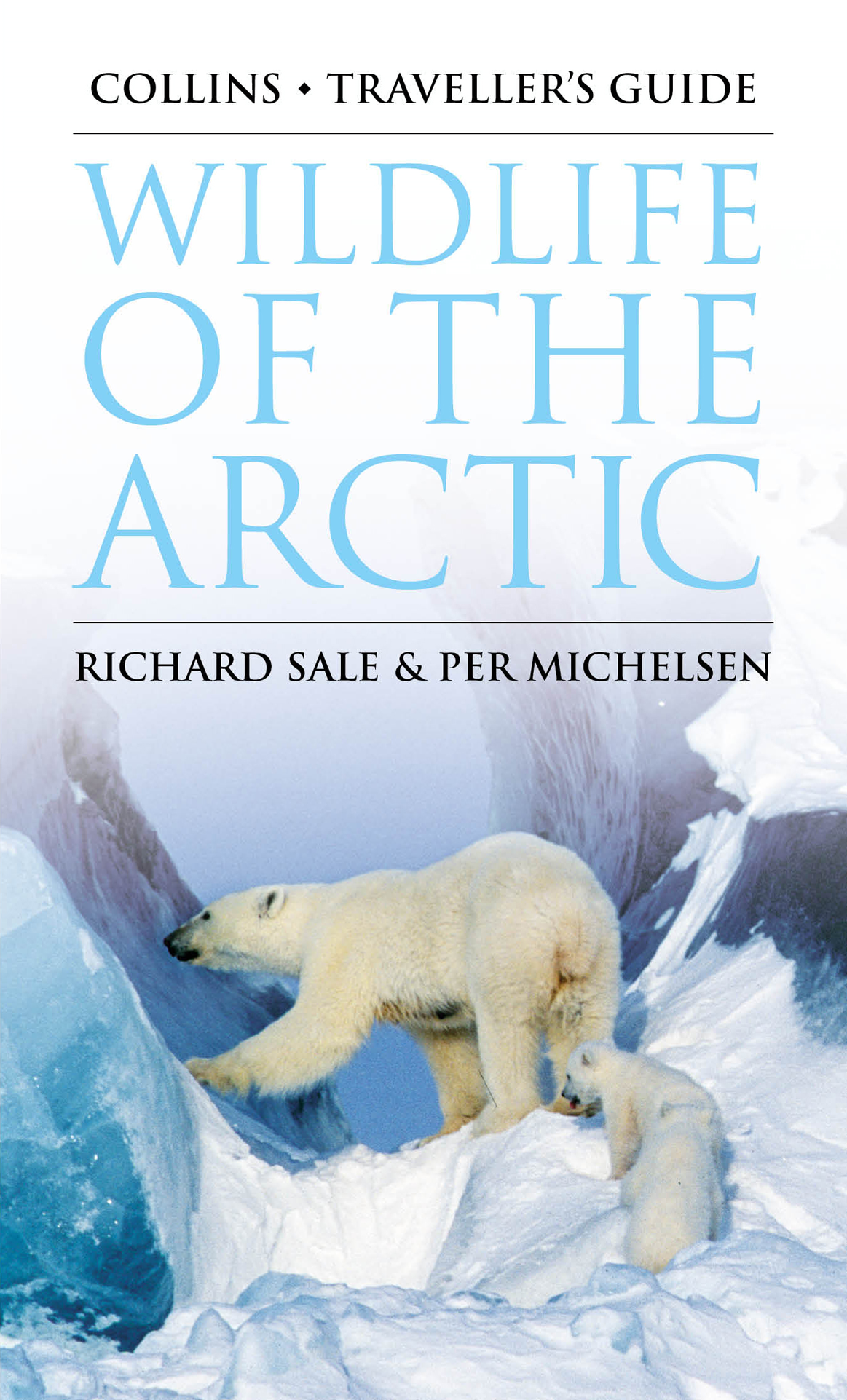

Front cover photograph Per Michelsen

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008205560

Ebook Edition February 2018 ISBN: 9780008205577

Version: 2018-03-05

To the continuing survival of the creatures of the North

CONTENTS

The listed page numbers and picture credits relate to the original paperback edition of this publication and should therefore be referenced in accordance with a copy of the physical book.

All photographs are by the authors with the exception of those listed below.

Alexander Andreev 47e, 177 b, c and d, 179f, 231g; Alexander Ladyguin 251c and d; Alpsdake 213a; Anatoly Kochnev 235c; Anne Markill, US Fish and Wildlife Service 235d; Ansgar Walk 289b; B Coster/FLPA 267d; Barney Moss 293c; Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, USA 213h, 241a; Bill Bouton 315e; Biosphoto/FLPA 277b; Cara Stanley, US Fish and Wildlife Service 47d; D Faulder 283e; D Hosking/FLPA 161d, 177a; Dave Soons 41c, 43e; David Castor 259g; Dick Daniels 37e, 67h, 71d, e and f, 79g, 125f, 131c, 149d, 151f, 179g, 187d; Donald Kramer 297f; Elaine R and Alan D Wilson 37f, 39c and e, 41d and e, 43f, 55c and d, 85c, d, e and f, 87e and f, 95a, 117c, 129a, 133a, 143b, 145b, 181c, 191b and c, 193e, 201a and b, 203f and g, 209g, 231c; Erik Christensen 293e; Erling Svensen 295g, 297a, d and h; Eugene Potapov 69d, 69e, 107g, 109b, 117d and 117e, 119c, d, e and f, 185e, 199e and f, 233f, 301b; F Nicklin/Minden/FLPA 287f, 289d and e, 291c; Francesco Veronesi 215d; Frank Vassen 123a; Greg Busker 293b; Igor Dorogoy 55e, 111d, 123c and d, 125c and d, 127c, 135d and e, 137c, 151d, 175d, 193b, 203a, 225a and d, 227e, 233e, 235e, 237c and e, 241d, 281e and g; Igor Shpilenok 117h; Irina Menushina 183a; Jacob W Frank, Denali National Park Service, USA 241e and f; Jens Bocher 299a and f, 301d and e, 303a; Jim Dau 229a; John Harrison 221f; Jon Nelson 103d; Jos Eugenio Gmez Rodriquez 285b; Kristine Sowl 149c; M Nishimura 223e; Marine World, Fukuoka, Japan 293d; Matt Witt 47c; Michelle L St. Sauveur 221e; Mike Baird 49e and f, 51c; Moira Brown/New England Aquarium USA 287b and c; Murray B Henson 207c; Nick Dunlop 111c; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, USA 271a, 283a, b, c and d, 285c; Pavel Tomkovich 39d, 137a, d, and g, 193f; Peter Myers 121a; Peter Pearsall, US Fish and Wildlife Service 151c; Phil Myers 37c, 55h, 67g, 71b, 117b, 207f, 209d, 217d, 223g, 225b and c, 237b and d, 255d, 269g, 303f, g, h, i and j; Photo Researchers/FLPA 179e; R Royse/Minden/FLPA 215b; Rick Simpson 129c; Robert Harding/Danny Frank 293a; Seabamirum 47f; Sindri Sklason 51d, 181a; Steve Hinshaw 143c and d; Teddy Llovet 189a;Terry Hall, US Fish and Wildlife Service 151e; Teteria Sonnna 237f; Thomas Kline 297b and c; Tim Bowman, US Fish and Wildlife Service 151a; Tuomo Jaakkonen 281f; US Fish and Wildlife Service 129b, 137b, 209e; Vladimir Burkanov 273f; Victor Golovnyuk 79f, 133b and c, 139a and b, 159e, f, g and h, 211b, c, d and e, 219g and h, 235b; Virginia State Park, USA 275a; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, USA 295f; Yuri Artukhin 223f, 273h.

Magdalenafjord, Spitsbergen, Svalbard.

In 1829 John Ross sailed to the Arctic. It was not his first trip north. On that first trip, an early British Royal Navy expedition to find a NorthWest Passage, he had retreated when apparently confronted with a range of mountains blocking the way east: he had probably seen a mirage of the type that was to deceive later explorers, but others on the trip urged him to continue. Back home his failure to do so led to vilification for a lack of gumption and Ross was ignored as a commander on later expeditions. The 1829 trip was privately financed, which explains his command, but the new trip went no better than the first. Ross was forced to overwinter in the ice, something he had avoided on his first trip. On that trip Ross had met Greenlandic Inuit, famously wearing full dress uniform to greet the skin-clad locals. On meeting the Inuit again, Ross wrote that it was for philosophers to interest themselves in speculating on a horde so small, and so secluded, occupying so apparently hopeless a country, so barren, so wild, and so repulsive; and yet enjoying the most perfect vigour, the most well-fed health, and all else that here constitutes, not merely wealth, but the opulence of luxury; since they were as amply furnished with provisions, as with every other thing that could be necessary to their wants. In that one sentence Ross encapsulated the lure of the Arctic for travellers from temperate regions to the south. The country was, as Ross contended, wild, but its wildness was also its beauty. Later travellers discovered a land that could not only be harsh and unforgiving, but a land of crystal, of silent cold, at times filled by the ghostly pale, trembling light of the aurora. Where the summer light was of breathtaking purity, but illuminated monochromatic scenery, white geese and swans on a black tundra, white ice on a dark sea, colour being rare and confined to summer. A land where the Sun, when it appeared after the Arctic night, could be cold and red and dishevelled, not the sun they knew. A land that seemed empty, with the people and animals being thinly spread so the loneliness could be awesome. Early travellers brought back tales of amazing creatures and of the endurance required of visitors, the Arctic becoming a land of inspiration and imagination. When Mary Shelley wrote her tale of Dr Frankenstein and the creature he created, she ends with the creature heading towards the North Pole.

The Arctic still inspires. Adventurers test themselves against it. Its wildlife still amazes when film and television show Earths natural wonders it is always the polar regions that draw the biggest audiences. But today the Arctic is in retreat. Humanitys relentless exploitation of the Earths resources in the pursuit of progress has altered the climate and threatens the ice and ice-living organisms. It is a clich that the loss of a species diminishes us, but it is true nonetheless. Even to people who have never seen a Polar Bear its loss will be immeasurable as the bear is iconic, both defining and reflecting the Arctic.

This book celebrates the Arctic, exploring the natural history that has so inspired generations.