authors note

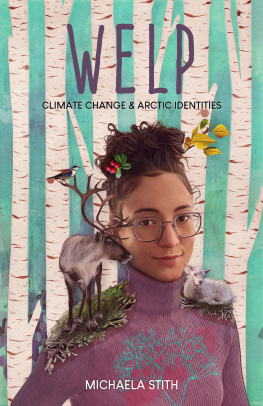

Ive been given a few nicknames in my life: Alaska, Mother Nature, even Mocha Mix. From birth, my mixed-race family took me fishing, hiking, and camping in Alaska. I adored sitting around the fire with my family eating freshly grilled Russian River salmon, picking wild northern blueberries from the hills around Anchorage, and waking up at four in the morning to ride my dads huge 4x4 to the boat dock. I remember his strong arms hoisting me to his chest while he clapped and sang, Im Black and Im proud!

My life drastically changed when my dad passed away. At his funeral, the two hundred people in attendance said his smile could light up a room. He was brilliant and kind, but he struggled with addiction and depression. When I was on spring break during sixth grade, my dad took his life while surrounded by law enforcement. Alaska has some of the highest per-capita rates of suicide, substance abuse, police brutality, gun deaths, and violent crimes in the country, anddamn it alltoo many of those trends impacted my own family.

When I talk about my dads death, people seem to think its shameful. Do you really want to talk about that here? they ask. Sure, it is excruciating for me to talk about it with people who dont understand systemic oppression. But I dont think his personal struggle is shameful; for me, too many people experience my dads same hurt to believe its all their fault. Even from a young age, I knew something was wrong with our government if it not only allowed but sponsored so many peoples suffering.

As a seventh grader in Mrs. Inglands geography class, I was assigned to write a travel brochure for any country in the world. I chose to write about Iceland: Iceland had had no murders in the last decades, few people in jail, and more examples of equality. Icelands snow-capped volcanoes and lichen-laid landscapes reminded me of home. If equity could be achieved in other parts of the Arctic, why not at home? My education had always challenged me to reimagine what our world could look like.

Since before my dad passed away, schools funneled me from one gifted program to another. Anchorage is a statewide hub, built on Denaina homelands, and the most diverse city in the country with over one hundred different languages spoken in our school district. Isolated in nearly all-white classes, I lived a life of relative privilege. I learned how to talk and fit into hide my vulnerabilities from othersbut I was always the butt of jokes about race and class. My teachers told us we would be the leaders of the next generation, but these students did not and could not represent Alaskans across the state. At some point in school, I decided I would have to be part of breaking down and making better systems of governance, from the inside out.

In college, I took advantage of all the opportunities Duke University had to offer: I lived in Iceland, visited Greenland, had amazing internships, protested racism on campus, and made friends from all over the world. I intentionally traveled back to Alaska every summer to wash showers and hand out clothes in a soup kitchen, canvass for environmental NGOs, help build resume-writing and job skills programs, and take notes at tribal meetings. This was on the universitys dime because (guess what!) these adventures are affordable for almost no one.

As a young adult, memories with my dad on the land were one reason why I chose to study environmental science and policy. I learned that the Arctic is warming at double the global rate, and human activities had created a new phase in Earths history: the Anthropocene. It became clear to me that racism and environmental change were both wrapped up in colonialism and white supremacy. I remained focused on the ultimate goal of making Alaska a better place and, when I graduated, that passion landed me funding to work abroad in Norway through Dukes Hart Leadership Fellows program.

I worked in international policy administration six hundred sixty miles above the Arctic Circle in Troms, Norway/Romssa, Spmi, following the direction of Indigenous Peoples organizations from across the North. I rode four-wheelers with reindeer herds in Guovdageaidnu, Spmi, climbed tundra-clad mountains on Senja Island, and volunteered as a security guard at music festivals. I sat around the table with foreign ministers and secretaries of state from the eight Arctic countries, occupied the same conference building as President Vladimir Putin in Moscow, and proofread the Sixth Arctic Leaders Summit Declaration, which highlighted Indigenous peoples visions for the future.

Some people have called me a very important person, to which I responded, No, I work for very important people. Ultimately, I wanted to be useful to Indigenous leaders in their political work. It was Indigenous leaders who got the Alaska Equal Rights Act passed back in 1945, which benefited all of us in Alaska. And they continue to drive justice movements in the state and the larger Arctic.

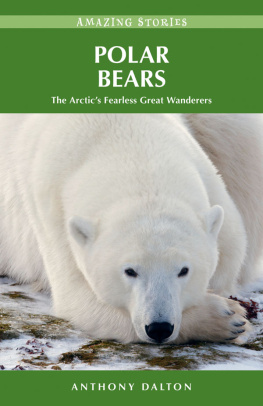

People like mewho only live in cities, fly country to country, organize meetings and administrate out of officesdont understand the environment in the intimate way people who live in one place and steward it do. While Indigenous people make up only 5 percent of the worlds population, they protect 80 percent of its biodiversity. That kind of stewardship doesnt look like national parks supported by scientists and nation-states; it looks like hunting, herding, fishing, and trapping with place-based knowledge and traditions passed through generations and over millennia.

Many people believe technical solutions and political reforms can potentially solve our biggest problems: climate change, institutionalized racism, and economic injustice. The problem is, consumption and economic growth are core tenets of the American culture and mindset. Decision-makers often need a college education and a masters degree to work in places like the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and only 13 percent of Americans have those qualifications. The people who make our countrys policies dont live traditional ways of life and certainly dont hold that Indigenous knowledge about how to care for the environment. Those who want to curb climate change propose large, new renewable energy projects like wind and solar farms. Generally, they are relatively wealthy people who perpetuate cultural norms about consumption. Many environmental policies end up hurting, rather than helping, people who live intimately with the environment.