For Michael The land is like poetry:

it is inexplicably coherent,

it is transcendent in its meaning,

and it has the power to elevate

a consideration of human life. BARRY LOPEZ

author of Arctic Dreams We must correct the global imbalances

caused by the great disconnections

that have grown between us. SHEILA WATT-CLOUTIER

Inuit climate change activist and

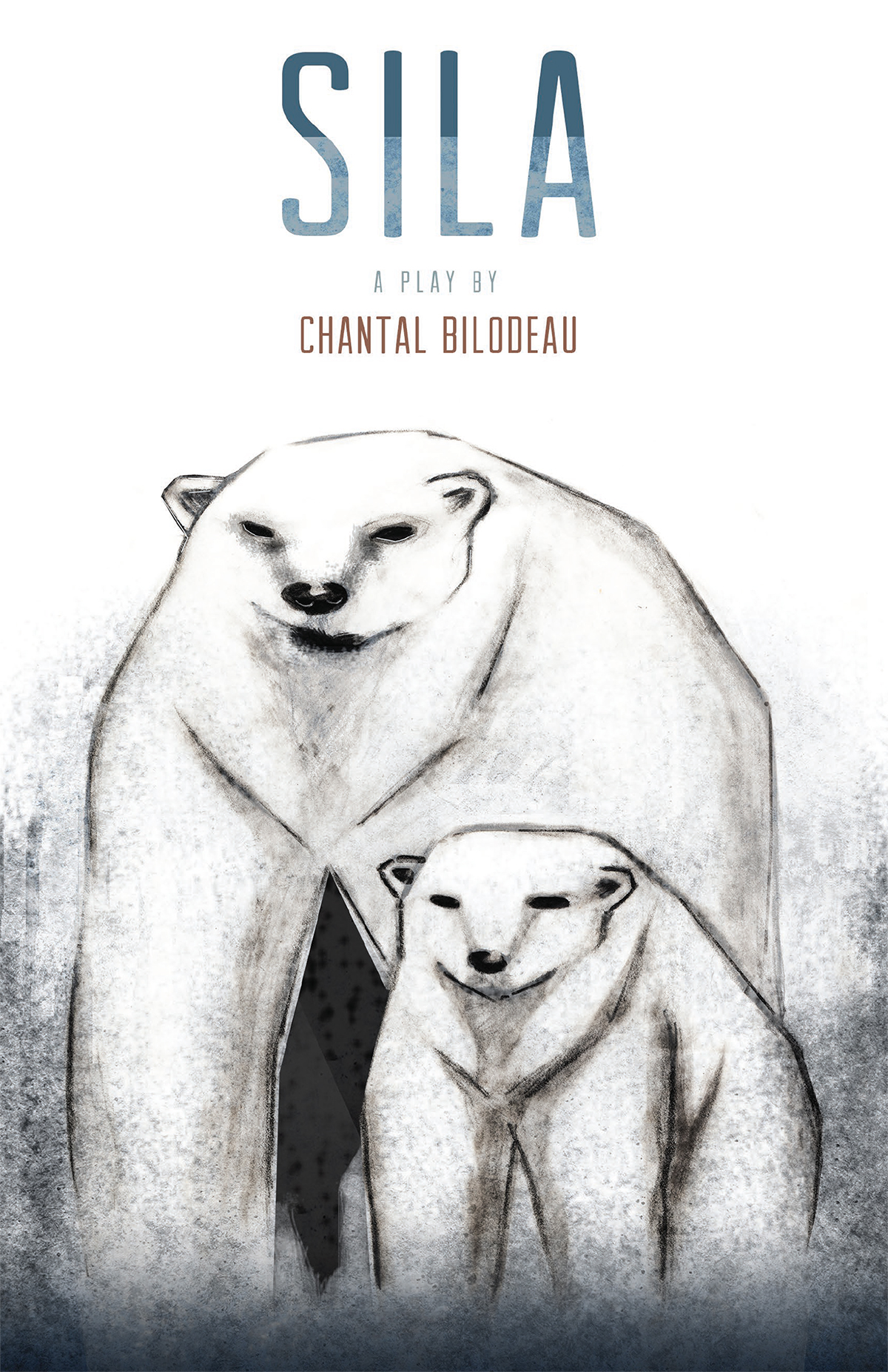

author of The Right to Be Cold The Arctic Cycle Sila is the first play of The Arctic Cycle a series of eight plays about the impact of climate change on the eight countries of the Arctic: Canada ( Sila ), Norway ( Forward ), Sweden, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, United States of America, and Russia. For more information: www.thearcticcycle.org.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION by Megan Sandberg-Zakian

I had the pleasure of directing the world premiere of Sila in 2014 at Underground Railway Theater, a resident company at Central Square Theater ( CST ) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In this ambitious and critically important play about our changing climate, the eight characters speak in three different languages, perform spoken-word poetry, travel silently across the arctic landscape, and explain the scientific and political realities of the region in rapid-fire short scenes cutting back and forth between indoor and outdoor locations in Iqaluit, a small city on remote Baffin Island.

Because Sila was produced through Catalyst Collaborative@ MIT , a partnership between CST and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology dedicated to increasing public understanding of science through theatre, we were charged with crafting a production that made visible not just the metaphor but the scientific reality of climate change. A series of world-class scientific advisers told us the most important things for the public to understand were: () We cant get back what weve lost. Its gone. () We must adapt to the unavoidable results of climate change. I knew our production needed to create a space that was simple and pristine enough for the technical information to be communicated effectively, and also beautiful and poetic enough for the impact of loss to be deeply felt on a large scale. The scripts inherent themes of interconnectedness and isolation were key, so from the beginning I envisioned a fluid white space that could merge or consume our locations of tundra, living room, Coast Guard office, and ocean.

Because I wanted to fill the entire room with shadow and reflective puppetry to achieve underwater and celestial locations, the set essentially had to be one giant projection screen. Scenic designer Szu-Feng Chen gave some structure to sheets of poly-satin by hanging walls of plastic bottles behind them which when lit from behind created eerie, architectural images reminiscent of ice formations. And then there were the polar bears the heart and soul of this play. Audiences have to fall in love with them, but not in a Disneyfied way. They need to be terrifying and heartbreaking. I worked with a wonderful puppet design and creation team, David Fichter and Will Cabell, along with a dramaturg, Downing Cless, who provided a wealth of practical information about the behaviour and biomechanics of polar bears.

We considered an array of different options, from more abstracted War Horse -like puppets, to simpler mask-like elements worn or manipulated by the actors, before arriving at a final design. Based on Inuit soapstone carvings, the puppets were about four fifths the size of actual polar bears, capturing the scale and muscularity, as well as the expressiveness and tenderness, of these impressive animals. I was surprised by how much rehearsal time these massive puppets consumed, but watching audiences wipe away tears at each performance, it was clear to me that the bears were a portal through which we humans are able to access the grief of our changing climate in surprising, profound ways. Underground Railway Theater is known for its use of puppets, so this approach made sense for us. However, we also did a series of public readings of the play without costumes or props and I dont think that the story of the polar bear characters was any less impactful without the physical puppets. Studying polar bear behaviour gives you a sense of the grace and intensity of these creatures and the intimacy of their relationships with each other and the land.

Actors that are able to capture those elements in their performances can be extremely effective with or without any bear-like elements. Speaking of actors: like any other play, the success of this production was 90 percent casting. I know it looks daunting! After all, the character breakdown has three Inuit characters, two French-speaking Canadian characters, one English-speaking Canadian character, two polar bears, and an Inuit sea goddess. In the Boston area, Id never met an Inuit person, let alone an Inuit actor, and we did not initially have the budget to bring in actors from out of town so it was clear that we would not be casting actors who were actually from all (or any) of those cultural backgrounds. Dangerous? Yes. There are so many instances where casting has failed to adequately make the case for a discrepancy between the racial makeup of the actor and the character such as contemporary productions that employ red face, casting actors without Native ancestry who are made up to look the part.

But there are also cases in which a more imaginative strategy for how to represent racial or ethnic differences onstage feels appropriate and respectful. After exploratory conversations with several colleagues of colour, I felt confident that Sila fell into the later category. I decided early on that it was important to cast non-white actors in the Inuit roles, both because of the endemic lack of opportunity for non-white actors in the American theatre, and also because of the very real racial and cultural differences between the Inuit and non-Inuit characters in the play. Since much of the story of the play rests on the relationship between traditional ways of life and the encroaching demands of modern technology and economics, a good local parallel seemed to be found in our own Native community. We did a fair amount of regional outreach as we sought to cast three different readings of the play prior to production. The diversity of our final casting pool was really exciting, including actors with mixed Native backgrounds as well as Philippino, Cambodian, Vietnamese, African American, French, Hispanic, and others.

It is not permissible to ask actors about their ethnicity during an audition process, and for good reason our business has a history of limiting, not expanding, opportunities for performers based on their race. Knowing this, and also knowing that fostering a culture of open communication around identity was crucial for this production, in which not a single actor in the play would share his or her characters cultural background, I looked for ways to open up a dialogue around race, culture, and representation that would allow performers to volunteer whatever information they felt comfortable sharing about their own background and their connection to the play. The beginning of our casting call stated, in bold type, Actors with Native American or First Nations backgrounds are especially encouraged to submit, prompting many interesting stories along with headshot submissions. In the audition, I made a point of asking, What did you think of the play? How do you personally relate to the character? Ill never forget one performer of Cambodian descent saying that the loss of culture and way of life of the Inuit people felt tragically close to what her own family had experienced. After casting was completed, I made sure each performer knew why I believed he or she was the best person for the role and that each understood the serious responsibility of embodying those who are not in the room to speak for themselves. My job was to challenge my diverse cast to fully access both our significant dramaturgical resources and their own personal experiences in order to vividly and respectfully bring these characters to life.