THE ENDS OF THE EARTH

An Anthology of the Finest Writing on the

Arctic and the Antarctic

THE ARCTIC

Edited by Elizabeth Kolbert

The Ends of the Earth: The Arctic, selection and introduction

copyright 2007 by Elizabeth Kolbert

The Ends of the Earth: The Antarctic, selection and introduction

copyright 2007 by Francis Spufford

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles

or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book,

but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers

would be glad to hear from them. For legal

purposes the acknowledgments on pages

207 (The Arctic) and 215 (The Antarctic) constitute extensions of the copyright page.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR

ISBN 978-1-59691-443-8 (hardcover)

First published by Bloomsbury USA in 2007

This e-book edition published in 2011

E-book ISBN: 978-1-60819-693-7

www.bloomsburyusa.com

CONTENTS

IN THE SPRING of 1888, the Norwegian doctor-cum-explorer Fridtjof Nansen set off for Iceland. He boarded a whaling ship in Isafjord and sailed to the east coast of Greenland. Once there, he strapped on a pair of skis and headed out across the ice sheet, a trip of some five hundred miles. Save for some problems with the pemmicanthe dried meat, which he had ordered from an outfitter in Copenhagen, was too lean, leading to a craving for fat which can scarcely be realized by anyone who has not experienced itthe journey went off without incident. Nevertheless, to get from Christianianow Osloto Godthabnow Nuukand back again took Nansen over a year.

In the spring of 2001, I set off for a research station known as the North Greenland Ice-core Project. I boarded a cargo plane in Schenectady, New York, and disembarked in Kangerlussuaq, on the islands west coast, six hours later. Another two-hour flightthis one on board an LC-130 equipped with skis and, for extra propulsion, little rocketstook me to North GRIP, at the very center of the ice sheet, at 75 06 N. In this way, I completed the first half of Nansens journey (albeit from the opposite direction) in less than a day. Perhaps if I had spent several weeks at the camp, I would have developed a craving for something; honestly, though, I cant imagine what. The afternoon I arrived, coffee and cake were served in the geodesic dome that doubled as the camps dining hall. In the evening, there was a cocktail party held in a chamber hollowed out of the ice. Dinner was lamb chops slathered in a tomato cream sauce, accompanied by red wine. As I recall, I skipped dessert that night; I was just too stuffed.

At least twenty scientists were living at North GRIP, and at no point did I wander far enough from the camp to lose sight of the tents. Yet if Arctic travel isnt quite what it used to be, now that the danger, hardship, and solitude have been sheared away, it is still an other-worldly experience. The white, the cold, the three A.M. sunthe scene was unlike anything I had ever encountered before. Of course, I came home and wrote about it.

This is a book of writings about the Arctic, which is not quite the same thing as a book about the Arctic. Almost all the selections are by outsiders to the regionexplorers, adventurers, anthropologists, novelists. The predominance of non-natives reflects the fact that Arctic people have, traditionally, transmitted their narratives orally, and also the fact that those who have been drawn to the area have, to an astonishing degree, felt compelled to record their impressions. Even today, the number of people who have traveled to the far north is tiny compared with the number who have traveled to Birmingham, say, or Philadelphia. Yet the literature of the Arctic is immense. Trying to choose the selections for this book, I sometimes felt as if everyone who had ever visited the Arctic had left behind an account of his or her (usually his) experience. In one of his many Klondike tales, An Odyssey of the North, Jack London compares the Arctic whiteness to a mighty sheet of foolscap and a dog team racing across the snow to a line drawn in black pencil. For a writer, the image is reversible, so that the blank pageand all its terrorscan also become a metaphor for the ice.

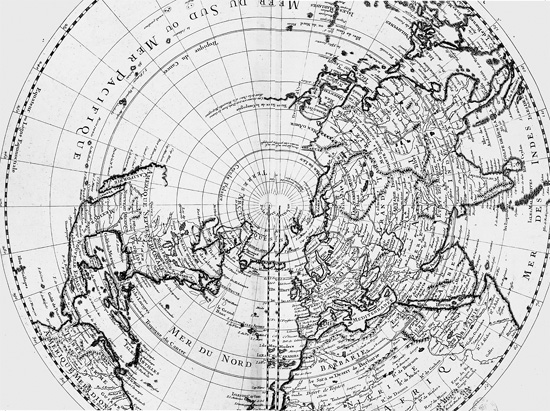

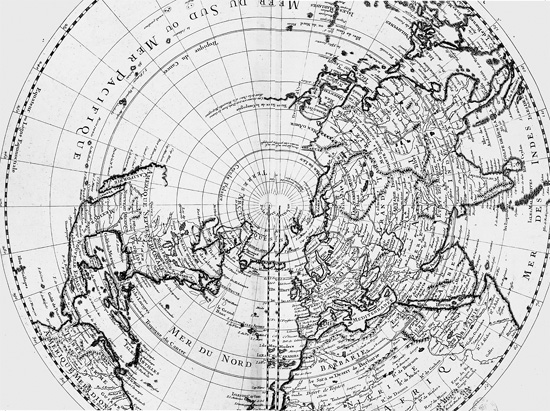

The Arctic is difficult to define. As Barry Lopez notes, There is no generally accepted definition for a southern limit to the region. To use the Arctic Circle as the boundary means including parts of Scandinavia so warmed by the Gulf Stream that they support frog life, while at the same time excluding regions around James Bay, in Canada, that are frequented by polar bears. (The Arctic Circle is designated as 66 33 N; however, owing to a slight wobble in the earths axial tilt, the real circle of polar night shifts by as much as fifty feet a year.) The works collected here touch on travels as far south as Iceland, which, except for the tiny tip of a tiny island, lies entirely below the Arctic Circle, and as far north as the pole itselfif, that is, you accept Robert Pearys claims to have made it there.

Though speculation about a mysterious, frozen island known as Thule dates all the way back to the Greek geographer Pytheas, this collection begins in the early nineteenth century. By that point, the search for the Northwest Passage was already well under way and had already claimed dozens of lives. It is sometimes suggested that this search was motivated by commerce and sometimes by nationalism. But neither force seems quite adequate; as the historian Glyn Williams has observed, the quest became almost mystical in nature, beyond reasonable explanation. I have chosen to focus on the most celebratedand most disastrousattempt to find a passage, that led by Sir John Franklin in 1845. Franklins disappearance prompted a string of rescue missions, many of which also ended badly, and one of which, organized by a Cincinnati businessman named Charles Francis Hall, may have culminated in murder. In the 1960s, Halls biographer, Chauncey Loomis, traveled to the shore of Thank God Harbor, in northern Greenland, where Hall had been buried, and had his body exhumed. It was in remarkably good shape, demonstrating the cold, hard truth that in the Arctic nothing is ever really lost.

The next generation of explorers was interested in only one direction: due north. I have included accounts of three efforts to reach the polethose led by Nansen, Peary, and Salomon August Andre. Nansens attempt involved spending a year in an icebound boatthe Fram, or Forwardand two more traversing the ice by dog sled. The farthest Nansen reached was as 86 14 N. This was 270 miles short of his goal, but at that point1895the highest latitude anyone had ever attained. Nansens Swedish rival, Andre, came up with the daring if impractical notion of besting him by balloon. With two companions, Andre set off for the pole from Spitsbergen on July 11, 1897. Three days later, after having drifted some 200 miles to the northeast, the balloonthe