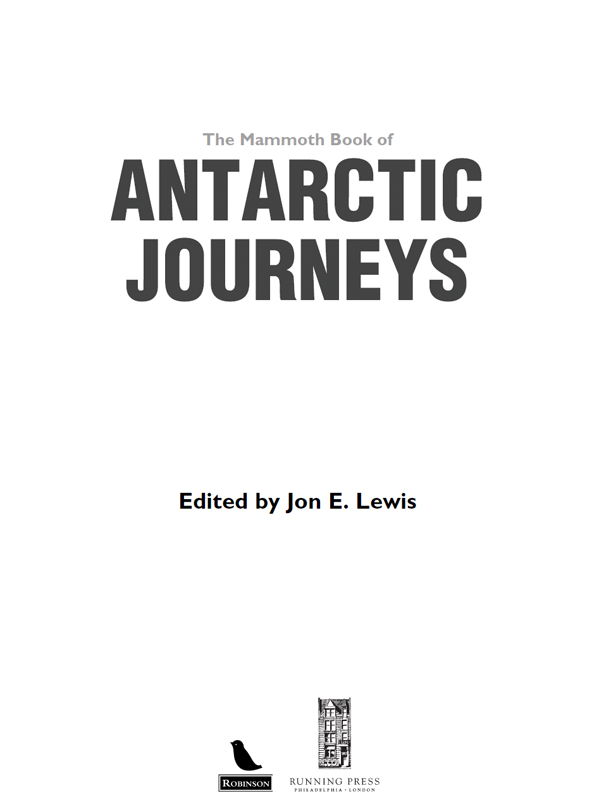

Jon E. Lewis is a historian and writer, whose books on history and military history are sold worldwide. He is also the editor of many The Mammoth Book of anthologies, including the bestselling On the Edge.

Recent Mammoth titles

The Mammoth Book of Chess

The Mammoth Book of Alternate Histories

The Mammoth Book of New IQ Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of Fun Brain-Training

The Mammoth Book of Dracula

The Mammoth Book of Best British Crime 8

The Mammoth Book of Tattoo Art

The Mammoth Book of Bob Dylan

The Mammoth Book of Mixed Martial Arts

The Mammoth Book of Codeword Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of New Sherlock Holmes Adventures

The Mammoth Book of Historical Crime Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Best New SF 24

The Mammoth Book of Really Silly Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 22

The Mammoth Book of Undercover Cops

The Mammoth Book of Weird News

The Mammoth Book of Lost Symbols

The Mammoth Book of Conspiracies

The Mammoth Book of Muhammad Ali

Constable & Robinson Ltd

5556 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2012

Copyright J. Lewis-Stempel, 2012 (unless stated otherwise)

The right of J. Lewis-Stempel to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication

Data is available from the British Library

UK ISBN 978-1-84901-722-0 (paperback)

UK ISBN 978-1-78033-134-8 (ebook)

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First published in the United States in 2012 by Running Press

Book Publishers, a member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved under the Pan-American and International Copyright Conventions

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher.

Books published by Running Press are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Digit on the right indicates the number of this printing

US Library of Congress Control number: 2010941556

US ISBN 978-0-7624-4275-1

Running Press Book Publishers

2300 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103-4371

Visit us on the web!

www.runningpress.com

Printed and bound in the UK

I am just going outside and may be some time.

Captain Laurence Titus Oates, c. 16 March 1912

Introduction: the South Pole

The South Pole, the southern end of the earths axis, lies within Antarctica, the worlds most hostile continent. This Geographical South Pole, distinct from the Magnetic South Pole (currently wandering Antarcticas Adlie Coast), is at an elevation of 9,300 feet, with 8,850 of those feet comprised of ice. James Cook, the English naval officer and explorer, was the first to cross the Antarctic Circle, a blasting berg-strewn experience which caused him to remark in his A Voyage Towards the South Pole (1777) that no man will ever venture further than I have done. Cook was wrong: A Voyage Towards the South Pole caught the European imagination and created a self-denying prophecy. Man upon man clamoured to sail South to see the sights described by Cook and to best his Southing record. There was money in it, too, for Cook had discovered seal- and whale-rich grounds around South Georgia. In 1820 Fabian Bellinghausen of Russia and Edward Bransfield of England, both sighted the Antarctic continent itself. James Rosss Royal Navy expedition of 1839 made the first Antarctic landfall, after which the British took a markedly proprietorial view of the white continent, just as they did of the Arctic. Thus the Norwegian Amundsens successful attempt on the South Pole in 1911, beating Scott of the Royal Navy, was a national tragedy, all the more so because Scott and his companions died in the doing. (There was also the British lament that Amundsens bid was not quite proper, for he had used dogs, rather than manhauling his sledges as the British did). Scotts journal of his last expedition assuredly one of the true masterpieces of travel-writing recorded an epic struggle against bad luck and Nature and preserved, to this day, the public opinion of the Antarctic as the fantasy ice palace of Heroes.

Which, of course, is not wide of the mark. Mawson, Shackleton, and Byrd to pick three post-Scott explorers at random all endured extraordinary struggles against the white death with a resoluteness of body and soul that can only inspire. But there is more to seek in Antarctica than the physical and mental limits of humankind. Scotts own expedition was (almost) as much about scientific research as it was polar conquest; to the very end Scott and his companions pulled along their weighty geological specimens. Today, the uninhabited continent is inhabited by some twenty scientific bases, prime among them the Amundsen-Scott base at 90 South, established to understand Antarcticas geology, ecosystem and weather. There is irony, even tragedy, in the scientific exploration of Antarctica: As David Helvarg finds in Melting Point, global warming is causing sections of the Antarctic ice-shelves to break off and glaciers to retreat: Where the Edwardian Antarctic explorers landed on a foreshore of ice, the modern visitor can step onto rocky beach. The immortal Antarctica of the heroes, in other words, is disappearing literally before our eyes.

Southing

Captain James Cook RN

In 1768 Captain James Cook, instructed by the Admiralty to find the Southern Continent speculated by geographers, made his first voyage towards the South Pole. Journeying due south from Tahiti to latitude 60 degrees, he disproved the existence of a temperate continent in the southern Pacific; for additional proof of the non-existence of such a continent he sailed south from the Cape of Good Hope in 1772, crossing the Antarctic circle without sighting land. The extracts below are from Cooks 1772 voyage.

Floating Rocks

Dangerous as it is to sail among these floating rocks (if I may be allowed to call them so) in a thick fog; this, however, is preferable to being entangled with immense fields of ice under the same circumstances. The great danger to be apprehended in this latter case, is the getting fast in the ice; a situation which would be exceedingly alarming. I had two men on board that had been in the Greenland trade; the one of them in a ship that lay nine weeks, and the other in one that lay six weeks, fast in this kind of ice; which they called packed ice. What they call field ice is thicker; and the whole field, be it ever so large, consists of one piece. Whereas this which

Next page