Contents

Guide

The remembrance of these experiences makes one almost fear to encourage good and brave men to penetrate these forbidding regions. But it is not all gloom and depression beyond the Polar circles. Sunshine and lively hope soon return.

Dr John Murray

Naturalist on the Challenger Expedition (187276)

The Renewal of Antarctic Exploration

Geographical Journal, January 1894

Thus, as knowledge grows, the power of the explorer increases, and the old-time hardships that we read of seem curious fantasies or epics of heroic men battling blindly with ignorance.

Dr Robert Rudmose-Brown

Naturalist on the Scotia Expedition (190204)

Some Problems of Polar Geography

Scottish Geographical Magazine, 1927

The great mystery of the South ever challenges to one fight more, and here death, dressed in storm, darkness, and cold, bandages no mans eyes.

Admiral Richard E. Byrd

Our Navy Explores Antarctica

National Geographic, October 1947

For the brothers Haddelsey,

Richard and Martin

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Stephen Haddelsey, 2018

The right of Stephen Haddelsey to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8880 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In examining the circumstances of so many fatalities it has, of course, been impossible not to form judgements regarding certain decisions made in the field. In doing so, I have been acutely aware of the potential criticisms that might ensue. After all, I was not there and I do not claim first-hand familiarity with the challenges of operating in Antarctic conditions. For this reason, as well as basing my accounts very closely upon contemporary diaries, letters, reports, inquests and interview transcripts, I have repeatedly sought the opinion of those who were there, and who have experienced the conditions for themselves. I am, therefore, particularly grateful to the following Antarctic veterans for sharing their recollections and views, and, in some cases, for reading portions of the manuscript: Ray Berry (FIDS), Ken Blaiklock OBE (FIDS & Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition), Dr John Dudeney OBE (BAS), Peter Gibbs (FIDS), Professor Rainer Goldsmith (Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition), John Hall MBE (BAS), Dr Graham Hurst (BAS), Dr Des Lugg (Australian Antarctic Division), Dr David Pratt CBE, FIMechE (Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition), Roderick Rhys Jones (BAS & British Antarctic Monument Trust), Pete Salino (BAS), the late Professor William Sladen MBE (FIDS), and Dr Yoshio Yoshida (Fourth Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition). Any opinions expressed, and mistakes committed, remain the sole responsibility of the author.

In addition, I have benefited enormously from the assistance of Billy-Ace Baker (American Polar Society), James Brooks (Head of Court and Tribunals Service, the Falkland Islands Government), Brian Dorsett-Bailey (brother of Jeremy Bailey), Mrs Irene Gillies (sister of Alistair Jock Forbes), Dr Henry Guly (BAS Medical Unit), Derek Gunn (son of Bernie Gunn), Professor Matthew Hall (Professor of Law & Criminal Justice, University of Lincoln), David Harrowfield, Dr David Keatley (School of Psychology, University of Lincoln), the Coroners Office of the Falkland Islands Government, Dr Peter Marquis (BAS), Mayumi Miyashita (National Institute of Polar Research, Japan), Richard McElrea (New Zealand Coroner), Gary Pierson (South-pole.com), Mrs Jocelyn Sladen (wife of Professor William Sladen), Robert B. Stephenson of the Antarctic Circle website (www.antarctic-circle.org) and Ivar Stokkeland (Norwegian Polar Institute).

In particular, I should like to express my gratitude to Ieaun Hopkins, Jo Rae and Beverley Ager of the British Antarctic Surveys Archives Department, whose expertise and generosity with their time have made researching this book infinitely easier than it might otherwise have been.

Finally, I should like to thank my wife, Caroline, and my son, George, for all their love and support and for heroically resisting the temptation to roll their eyes when I began to regale them with yet more anecdotes relating to the exploration of Antarctica.

Stephen Haddelsey

Halam, Nottinghamshire

September 2017

AUTHORS NOTE

In writing this book my intention has not been to provide a comprehensive list of every fatality suffered during the exploration of Antarctica, for such a list I refer the reader to John Stewarts excellent Antarctica: An Encyclopedia (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 1990). Instead, I have sought to identify a range of accidents which, arranged thematically, should serve to highlight some of the more common hazards faced by those who, over the course of the last century or so, have been actively engaged in pushing back the boundaries of our geographic and scientific knowledge of the continent.

For a number of reasons, which include language, accessibility and the comprehensiveness of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) Archives, many of the examples cited are from the United Kingdom; however, so far as has been practicable, I have included representative stories from as many nations as possible, including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Finally, I have chosen, quite deliberately, to restrict myself to deaths that have occurred during expeditions dedicated to the exploration and scientific investigation of the continental landmass, the vast majority of these being government sponsored. Excluded, therefore (with only two exceptions), are casualties sustained at sea, during tourism, and in privately organised small-scale ventures where tests of human endurance are the aim rather than a consequence of the exercise.

INTRODUCTION

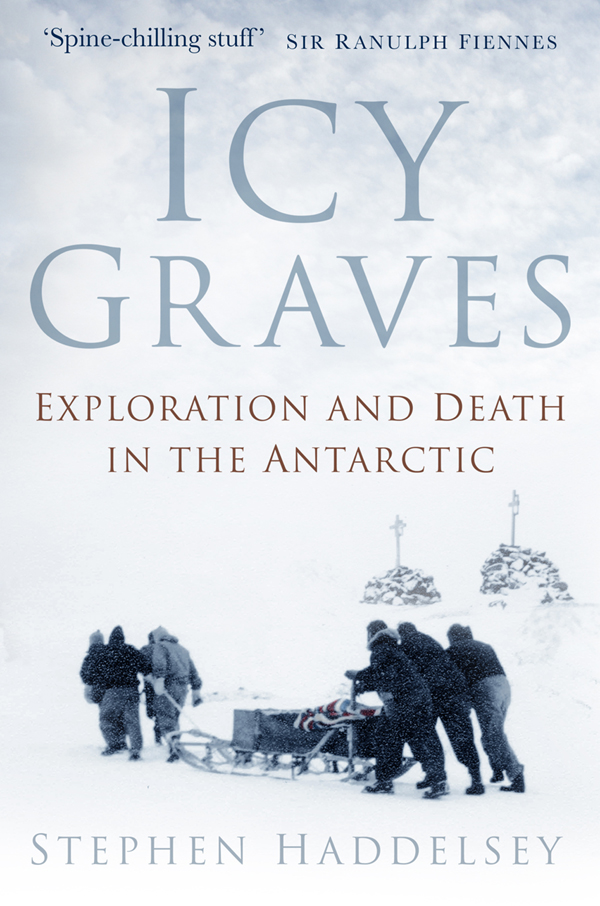

On the morning of 22 January 1913, a party of eight men struggled to the summit of Observation Hill on the south-west tip of Ross Island, Antarctica. Between them they carried a 3.5m-long cross of Australian mahogany gum tree, or Eucalyptus marginata, a densely grained hardwood known to the Aborigines as jarrah. It was a heavy job, wrote the amateur zoologist Apsley Cherry-Garrard that evening, and the ice was looking very bad all around, and I for one was glad when we had got it up by 5 oclock or so.

Once slotted into a hole dug the previous day, the white-painted cross stood 2.5m tall, commanding McMurdo Sound on one side and the barren white wasteland of the Ross Ice Shelf, or the Great Barrier as it was then known, on the other. It is really magnificent, Cherry-Garrard enthused, and will be a permanent memorial which could be seen from the ship nine miles [14.5km] off with a naked eye I do not believe it will ever move.