Sources

Institutions visited to obtain source material included the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, the Royal Geographical Society, London, United Kingdom, the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand, the James Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, United Kingdom, the Melbourne Museum, Melbourne, Australia, and the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

The primary sources used were Richards interview with L. Bickel in 1976, Richards interview with P Lathlean in 1976, Richards interview on the Australian Broadcasting Commission Verbatim program broadcast in 2002, Richards interview with P. Law in December 1980, and the field diaries of Victor George Hayward, Ernest Edward Mills Joyce, Aeneas Lionel Acton Mackintosh, Richard Walter Richards, Arnold Patrick Spencer-Smith, Harry Ernest Wild and Irvine Gaze.

Secondary Sources included: Shackletons Heroes by the author, Antarctic Diaries of D. Mawson, Antarctic Historic Huts. New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust booklet, Antarctic Padre,A.J.T.Fraser, unpublished, Bio of Frank Wild, Thompson, unpublished, Hayward, radio telegram to Ethel Bridson, Hayward, Peter John, Grand-nephew of Victor Hayward, private papers, Joyce letters, Mackintosh letters, Medical Report of the Ross Sea Base ITAE, January 1917. J.L. Cope, Naval Service Record of Ernest Edward Mills Joyce, No: 160823, Naval Service Record of Harry Ernest Wild, No: 181904, Old Woodbridgian school magazine, Woodbridge School, Suffolk, UK, Anne Phillips, Anne, granddaughter of Aeneas Mackintosh. Private papers, and interview, Report of Proceedings of the Aurora Relief Expedition 1916-1917, Richards Agreement with Shackleton, written December 1914, at Sydney, Australia, Richards Agreement with Shackleton, written January 18th, 1916 in Antarctica, Richards letters and lettergrams to Mackintosh, Richards, various letters to historians, A.J.T. Fraser and L.B. Quartermain, Richards papers at the Art & Historical Collection, Federation University (formerly University of Ballarat), Scotts last Expedition, The Journals. Shackletons letters to Mackintosh, Shackleton letter to his wife Emily, August 17, 1914, Shackletons lieutenant: The Nimrod diary of A.L.A. Mackintosh, South by E.H. Ernest Shackleton. Spencer-Smith letters, The Dial, Queens College Magazine, Queens College, Cambridge, UK, 1907, The Eagle, Bedford Modern School (BMS Archives). Journal of 1917, The Heart of the Antarctic Vol 1 by E.H. Shackleton, The Ross Sea Shore Party by R.W. Richards, The South Polar Trail The Log of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition by Ernest Joyce, Voyage of the Discovery by R.F. Scott, To the South Pole by Roald Amundsen, Willesden Chronicle newspaper, Willesden Green, UK and With the Aurora in the Antarctic by J.K. Davis.

CONTENTS

|

|

|

| Chapter 1 |

|

| Chapter 2 |

|

| Chapter 3 |

|

| Chapter 4 |

|

| Chapter 5 |

|

| Chapter 6 |

|

| Chapter 7 |

|

| Chapter 8 |

|

| Chapter 9 |

|

| Chapter 10 |

|

| Chapter 11 |

|

| Chapter 12 |

|

| Chapter 13 |

|

| Chapter 14 |

|

| Chapter 15 |

|

| Chapter 16 |

|

| Chapter 17 |

|

| Chapter 18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

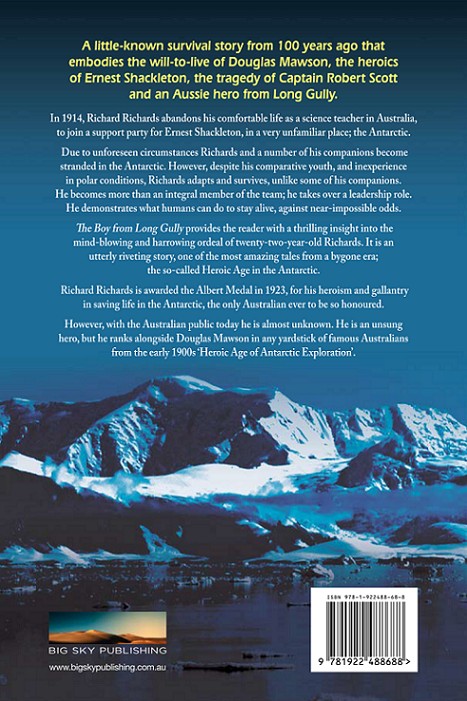

Copyright Wilson McOrist

First published 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission.

All inquiries should be made to the publishers.

Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 303, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia

Phone: 1300 364 611

Fax: (61 2) 9918 2396

Email:

Web: www.bigskypublishing.com.au

Cover design and typesetting: Think Productions

Foreword

There was a critical time in my crossing of South Georgia in 2013, where I was imprisoned in a tent with two companions. Sixty to eighty knot winds raged outside, and hypothermia and frostbite stalked us all. Thirty-six hours into our incarceration I recall the words I wrote in my book Shackletons EPIC, describing our decision to press on: We surveyed the scene outside. It was still a maelstrom, but the wind gusts had diminished in their severity and the sleet had stopped. Its now or never, said one of my companions. Lets make it now.

My experiences give some insight into what young Australian Richard Richards faced in 1916, during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Richards, with five (English) companions, was just 10 miles from a food depot on the Great Ice Barrier when a fierce blizzard halted their progress. The blizzard raged without let-up for days and the six men ran out of food, and fuel to even melt snow for a drink. They knew they were ominously close to where Scott, Wilson and Bowers had died on the Great Ice Barrier a few years earlier, but Richards and two men refused to stay in their tent and die. They decided to brave the blizzard. We are in a very weak state, but we cannot give in. However, we get underway!

Then, Richards wrote that it was a desperate time that forced he and his two companions out into the blizzard to reach a food depot and return to rescue the three others. In 2007, for me, as I recreated the 1913 survival feat of Douglas Mawson, I searched for a word that described the hardship of surviving on my own in the dreadful conditions he faced. The word that immediately came to mind was desperate.

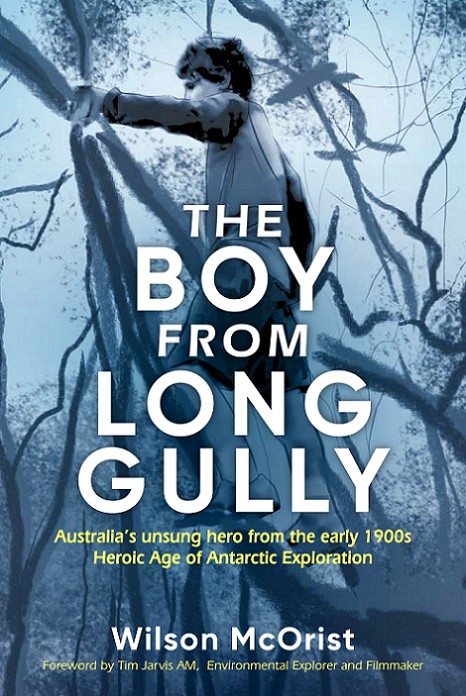

The story of Richard Richards heroics in the Antarctic, as a member of a support party for Shackleton, are brought to life in Wilson McOrists book, The Boy from Long Gully. In 1914, Richards joined a support party for Ernest Shackleton, and he became embroiled in one of the greatest stories of endurance in the history of polar exploration. Shackleton was planning to cross the Antarctic continent but needed several food depots to be put down by a support party. Despite many difficulties, Richards and his five English companions completed their given task, all the depots were put in place, but then they had to return to safety, over 360 miles across the Great Ice Barrier. Wilsons book brings to life their little-known survival story, from 100 years ago. It is an unrelenting tale that embodies the will-to-live of Douglas Mawson, the heroics of Ernest Shackleton and the tragedy of Captain Robert Scott.

There are many aspects of Richards life in the Antarctic that I can relate to.

When we left Elephant Island in our replica James Caird the Alexandra Shackleton, it was our Primus stove that brought some relief to our conditions. Baz had got the Primus going, its glow making those of us on deck feel warmer than the -5C should have allowed us to. One of Richards companions wrote of similar feelings: I write this sitting up in my bag, while the primus is going as an extra luxury, and another: How cheery the Primus sounds, it seems like coming out of a thick London fog into a drawing room.