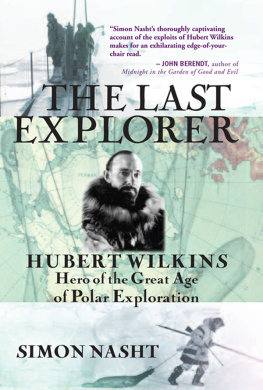

Copyright 2005, 2011 by Simon Nasht

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

First published in Australia and New Zealand in 2005 by Hodder Australia

All photographs courtesy of Ohio State University

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61608-717-3

In memory of Constance Perkin (1900-2000)

and all the unsung heroes of the century

Acknowledgments

I must principally thank two Norwegians, Trond Eliassen and KjellEriksen, who first introduced me to a forgotten explorer from my own country. Their enthusiasm for Wilkins was inspiring and their contribution to my research cannot be overstated. The fact checkers at National Geographic Television inadvertently sent me on a search to correct some long-standing myths, and this book is the result. Any errors however are mine.

The largest collection of Wilkins papers is, ironically enough, held in the institute named after his greatest rival. My sincere thanks to all at the Byrd Polar Research Center at the Ohio State University, primarily Polar Curator Laura J. Kissel, who has been exceptionally helpful with her time and assistance.

Professor Peter Wadhams, former director of the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, and his wife, the polar historian Dr. Maria Pia Casarini, were the first to alert me to the significance of Wilkins scientific achievements and generous in sharing their extensive knowledge.

Other collections concerning Wilkins are spread around the world and I am thankful to the many curators and archivists who assisted me, including J. J. Ahern at the American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia; Janet Baldwin, Curator of Collections, James B. Ford Library, The Explorers Club, New York; Sarah Hartwell, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College; and the archivists of the Natural History Museum, London.

The work of Stuart Jenness, son of Wilkins good friend from the Canadian Arctic Expedition, Diamond Jenness, has been invaluable. Stuart spent many years deciphering Wilkins impossible handwriting and I am eternally thankful that this difficult task was accomplished at the expense of someone elses eyesight. Vice Admiral James Calvert suffered without complaint through my obvious ignorance of submarining. His moving account of Wilkins funeral service at the North Pole is included almost verbatim.

Thomas Endrusick and former colleagues of Sir Hubert at the U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center, Natick, Massachusetts, were diligent in collecting useful information. Climatologist Dr. William Porter, a man after Wilkins own heart, is well into his eighties and still working there, and I appreciate sharing his memories of their pioneering days together.

In Australia Ross St. Clair gave valuable advice on his grandfather, aviation pioneer Garnsey Potts, and other early Australian aviators. Nick Klaasens research into the history of the Wilkins family helped me piece together the formative years as did Dr. Jeff Nicholas, president of the Pioneers Association of South Australia.

Antarctic veteran Dr. Phillip Law and Stephen Martin of the State Library of New South Wales have given invaluable guidance on polar history. Alasdair McGregor, biographer of Frank Hurley, shared his immense knowledge and gave generous advice. The Australian Antarctic Division was superb, and its choice of guide, Ian Godfrey of the Western Australian Museum, made my stay in Antarctica both safe and productive. My thanks to Don and Margie McIntyre and the crew of the Sir Hubert Wilkins for making my passage of the Southern Ocean an authentic adventure.

For their faith and patience, I am indebted to Matthew Kelly and Isobel Dixon. To my family, who endured endless retellings of Wilkins stories without loss of enthusiasm, I am forever grateful.

Contents

Introduction

Looking down from the well-trodden trails and peaks first climbed by others, we feel a mixture of awe and envy at the achievements of the past centurys great explorers, the last of the first. For they, unlike us, had the unknown ahead of them, challenges that tested the limits of human endurance and courage. Using only the simplest technologies and rudimentary chartsif they had any at allthese few removed the last corners of terra incognita from the maps and from our imaginations.

In the various polar and geographic institutes of Britain, Australia, Scandinavia and the United States, the same names appear again and again. We know them now as the giants of the brief, dramatic period of exploration called the heroic age: Amundsen, Peary, Scott and Shackleton, with Mawson, Nansen and Byrd just a step behind. One after another they and their kind conquered the poles, climbed the high mountains, crossed the remaining oceans and deserts, and mapped the last land. Many tried, a handful succeeded. But even those few who triumphed were often left so drained by the experience they could never savour victory. They crossed the void only to be left empty within.

Ultimately these were men of action, driven by a curious mix of ego, courage and duty, but mostly by the fear of being beaten to their prize. Though they manfully hauled back the rock samples and books full of weather data, each knew history would judge them by a simple test: did they win?

It was on a visit to the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge that I was first made aware of the true significance of a man few have heard of: Sir Hubert Wilkins. While I had been fascinated by his daring and often amusing adventures, somehow it seemed disrespectful to consider him in the same light as the great men of the heroic age. But the institutes former director, Professor Peter Wadhams, and his polar historian wife, Dr. Maria Pia Casarini, were pleased that someone had finally come to investigate further the life of a man they considered the first truly modern explorer and perhaps the finest of the twentieth century. They saw him as a visionary who realised the change that modern technology could bring to exploration and its often neglected sister, scientific research. Wilkins was the one who put to rest the notion that all that mattered was to be there a day before anyone else, and who finally reversed the heroic equation of glory before knowledge.