Contents

Guide

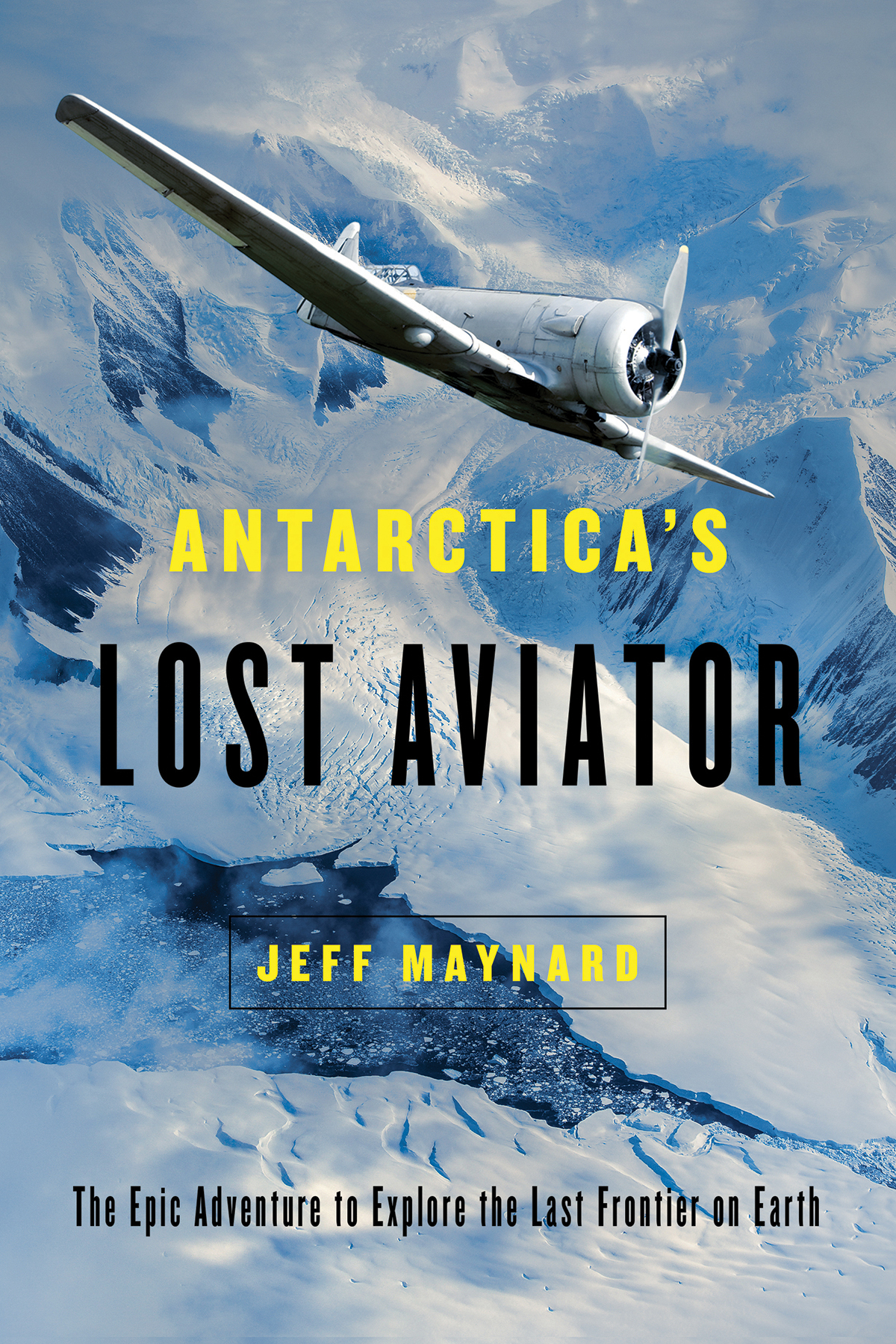

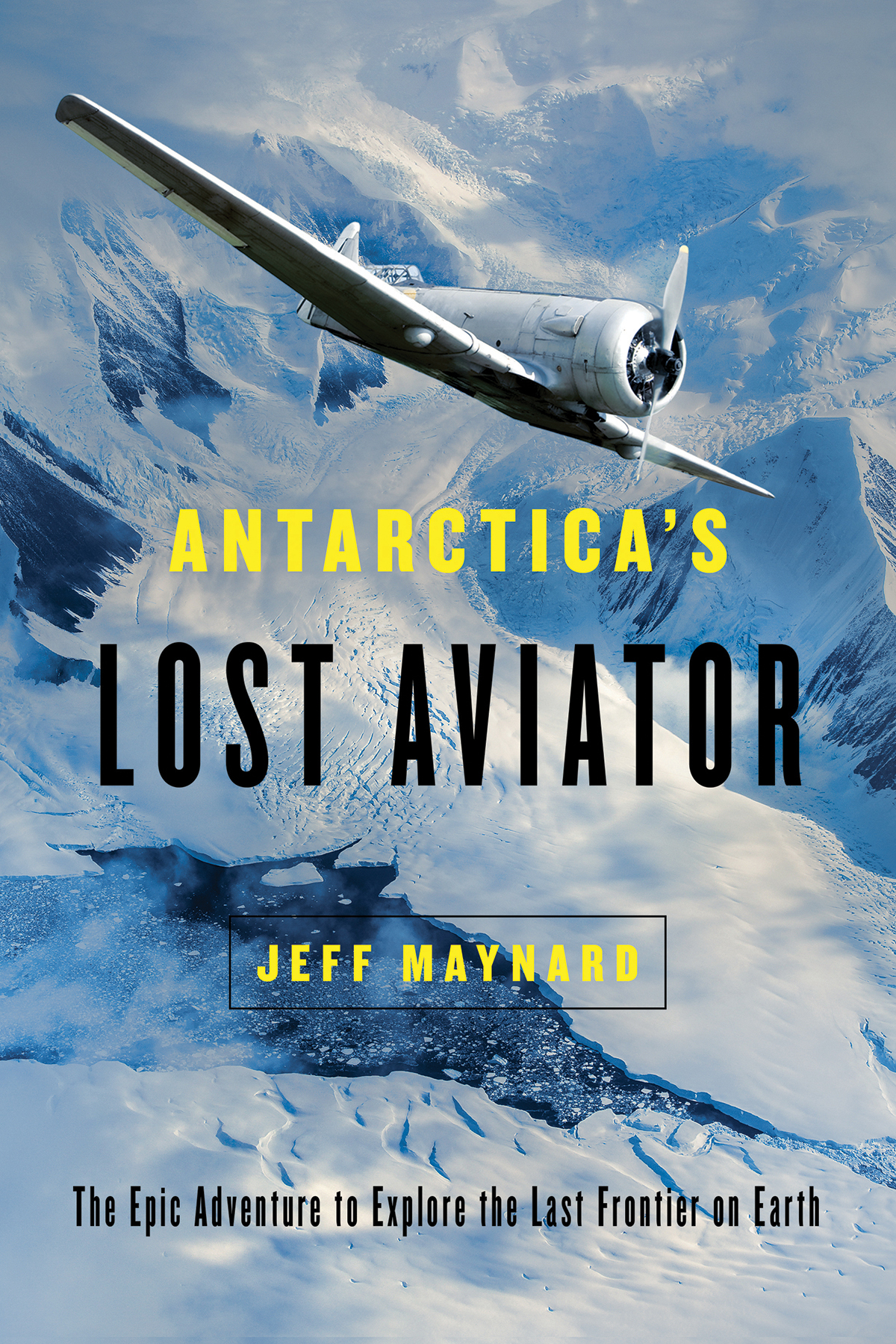

ANTARCTICAS LOST AVIATOR

The Epic Adventure to Explore the Last Frontier on Earth

JEFF MAYNARD

ANTARTICAS LOST AVIATOR

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W. 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Jeff Maynard

First Pegasus Books cloth edition February 2019

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: is available.

ISBN: 978-1-64313-012-5

ISBN: 978-1-64313-096-5 (ebk.)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

For Annabelle, Bethany, Baxter, and Wes.

May they soar over new frontiers.

CONTENTS

B y the end of World War I, about five percent of the Antarctic landmass had been explored. A small wedge from the Ross Ice Shelf to the South Pole was the only area of the vast interior impressed by a human footprint, and less than one third of the coastline had been sighted. During the 1920s and 1930s, as new areas were added to maps, inaccurate names were sometimes assigned to them. For example, in 1928, when Sir Hubert Wilkins flew along what we now call the Antarctic Peninsula, he incorrectly reported it to be a series of islands. As a result, maps of the period showed it as the Antarctic Archipelago. (The northern section was known as Graham Land and the southern section as Palmer Land.) In other cases, names were assigned, then altered as areas underwent more definitive mapping, or mapmakers chose to be more concise. Hearst Land moved and became Hearst Island. James W. Ellsworth Land was, for a period, Ellsworth Highland and is now simply Ellsworth Land. For consistency with quoted passages and maps, I generally adopt the names the explorers used, only offering an explanation when necessary to avoid confusion. I have also included maps, showing the known areas of Antarctica at the commencement of the Ellsworth expeditions, along with Wilkinss map of the Antarctic Archipelago drawn in 1930.

Navigation held special difficulties for polar aviators during the 1930s. Their instruments and methods were evolving from those used by mariners, who took sextant readings at sea level. So in addition to the difficulties associated with traveling at a much higher speed, navigators cramped in a cockpit also had to estimate their altitude, which was problematic over unexplored land, where the heights of mountains were unknown. Also, mariners sailed in lower latitudes, where meridians of longitude are farther apart and magnetic compass variation is less acute. Because I didnt want to slow the narrative with lengthy explanations, an overview of the methods employed by Lincoln Ellsworth to cross Antarctica is included as an appendix, along with the instructions, estimated positions, and compass variations for the flight, as compiled by Sir Hubert Wilkins.

For period authenticity, I have usually retained the terms and expressions that were used by the explorers. Hence, distances are in miles, length in feet and inches, and weights are generally quoted using imperial measures. The only exception to the use of imperial measures are gallons, which are U.S. I include the metric equivalent to weights, capacity, and distance where I feel it may assist understanding. Unless otherwise stated, miles are statute rather than nautical.

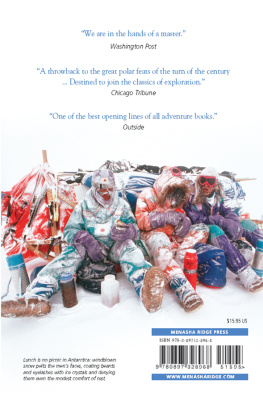

T he surviving black-and-white film shows two men preparing for a flight beside a sleek metal airplane. Behind the plane, flat compacted snow stretches, like a theater backdrop, to a distant horizon of gently sloping hills. Scattered about the snow in front of the plane are drums of fuel, bags of supplies, and a lightweight wooden sled.

Both actors in the unfolding drama are tall men. Lincoln Ellsworth is the slimmer of the two. His youthful face and thick head of hair make him appear younger than his fifty-five years. Ellsworth is pulling a thick fur parka over his upper body and adjusting the hood. He smiles and briefly spreads his arms wide to present the accomplishment to the camera, then looks around the snow for something to load aboard the plane.

The other man is Herbert Hollick-Kenyon. He is wearing trousers, boots, a check woollen shirt, and aviator sunglasses, which hide his eyes. His solid build and receding hairline make him look older than his thirty-eight years. He ignores the camera as he suits up, deftly clamping the stem of a lighted pipe in his teeth, then transferring it to his hand. The dexterity is impressive and performed without a hint of self-consciousness.

Near the plane, the flags of the institutions with which Ellsworth has an association are held on bamboo poles, a horizontal strut ensuring each is clearly visible in the still air. The camera pans across the flags of the National Geographic Society, Yale University, the New York Athletic Club, the Hill School, Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and, towering over them all, the flag of the United States of America with forty-eight stars. (In 1935, Alaska and Hawaii are not yet states.) Ellsworth smiles proudly at the camera again and, on the soundless film, goes through the carefully choreographed motion of pointing to each flag in turn.

The film jumps to the same scene a few minutes later. The flags have been packed away. Hollick-Kenyon is sitting casually on the snow, his pipe still in his mouth, strapping gaiters over his boots. He too is now wearing a fur parka.

Ellsworth is pacing anxiously in front of the plane. In his right hand he carries a leather cartridge belt, devoid of bullets. The wealthy Ellsworth who owns, among other things, mansions in New York and Chicago, a villa in Italy, a castle in Switzerland, and great works of art, considers this old cartridge belt his most precious possession. It is the good luck charm he will carry on the flight he hopes will write his name in the history books. The belt would have no value and no meaning were it not for the fact it was once owned by Ellsworths hero, the western lawman Wyatt Earp. The belt has made a long journey from one frontier to another.

The film jumps again and bit players have walk-on roles in the performance. A mechanic checks the engine, more for the camera than mechanical necessity. Everything has already been checked and rechecked. Another man steps on the low wing and wipes the cockpit windscreen with a cloth. And it goes on until Hollick-Kenyon and Ellsworth are ready to climb aboard.

Hollick-Kenyon climbs in first, sliding the canopy to the rear and maneuvering his bulky frame into the narrow cockpit. He reaches up and pulls the canopy forward, over his head, so Ellsworth can climb into the seat behind him. Settled, Ellsworth grins at the camera and, reacting to some unheard direction, leans awkwardly forward, thrusting his head partway out of the cockpit, so his face is not in shadow.

A man closes the side hatches on the fuselage before walking out of frame. The streamlined silver metal plane is beautiful, even by modern standards. The large block letters along the side are clearly visible: ELLSWORTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC FLIGHT .