Copyright 1991 by Will Steger and Jon Bowermaster

First trade paperback edition 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Menasha Ridge Press

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

ISBN: 978-0-89732-896-8

Cover and text design by Fiona Stewart

Cover photograph by Damion Morrissott

Back cover photograph by Will Steger

Author photograph of Will Steger by Roger Rich

Author photograph of Jon Bowermaster by Fiona Stewart

M ENASHA R IDGE P RESS

P.O. BOX 43673

Birmingham, Alabama 35243

www.menasharidge.com

Dedicated to the preservation and protection of Earths most paradoxical continent.

What castles one builds, now hopefully that the Pole is ours!

Robert Falcon Scott, January 5, 1912

The Pole. Great God! This is an awful place.

Robert Falcon Scott, January 17, 1912

20 YEARS LATER NEW INTRODUCTION

On July 26, 1989, I saw Antarctica for the first time. Along with my expedition partner, French doctor and explorer Jean-Louis Etienne, and our teammatesVictor Boyarsky (Russia), Geoff Somers (UK), Keizo Funatsu (Japan) and Qin Dahe (China)Id been training and dreaming of this moment for several years.

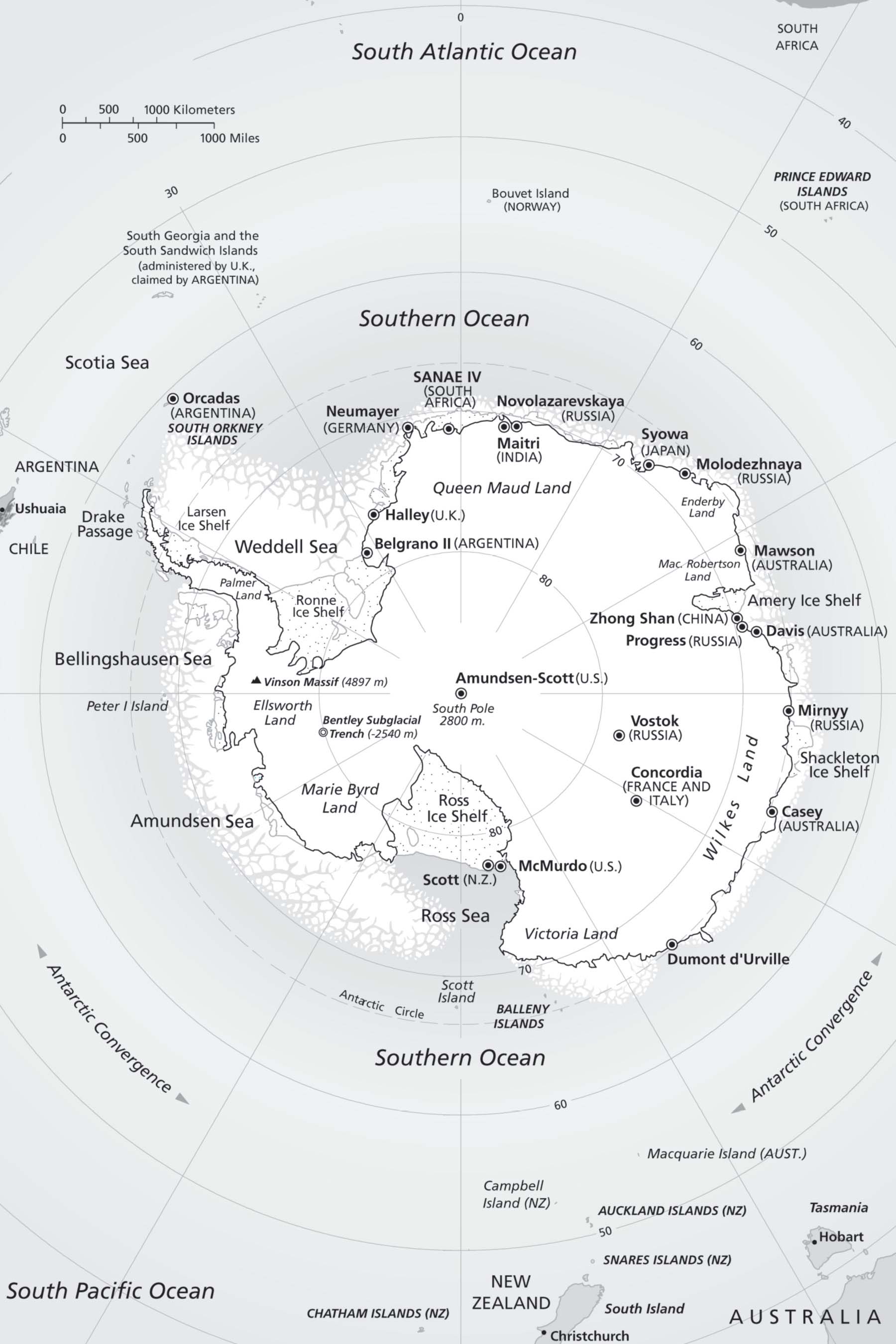

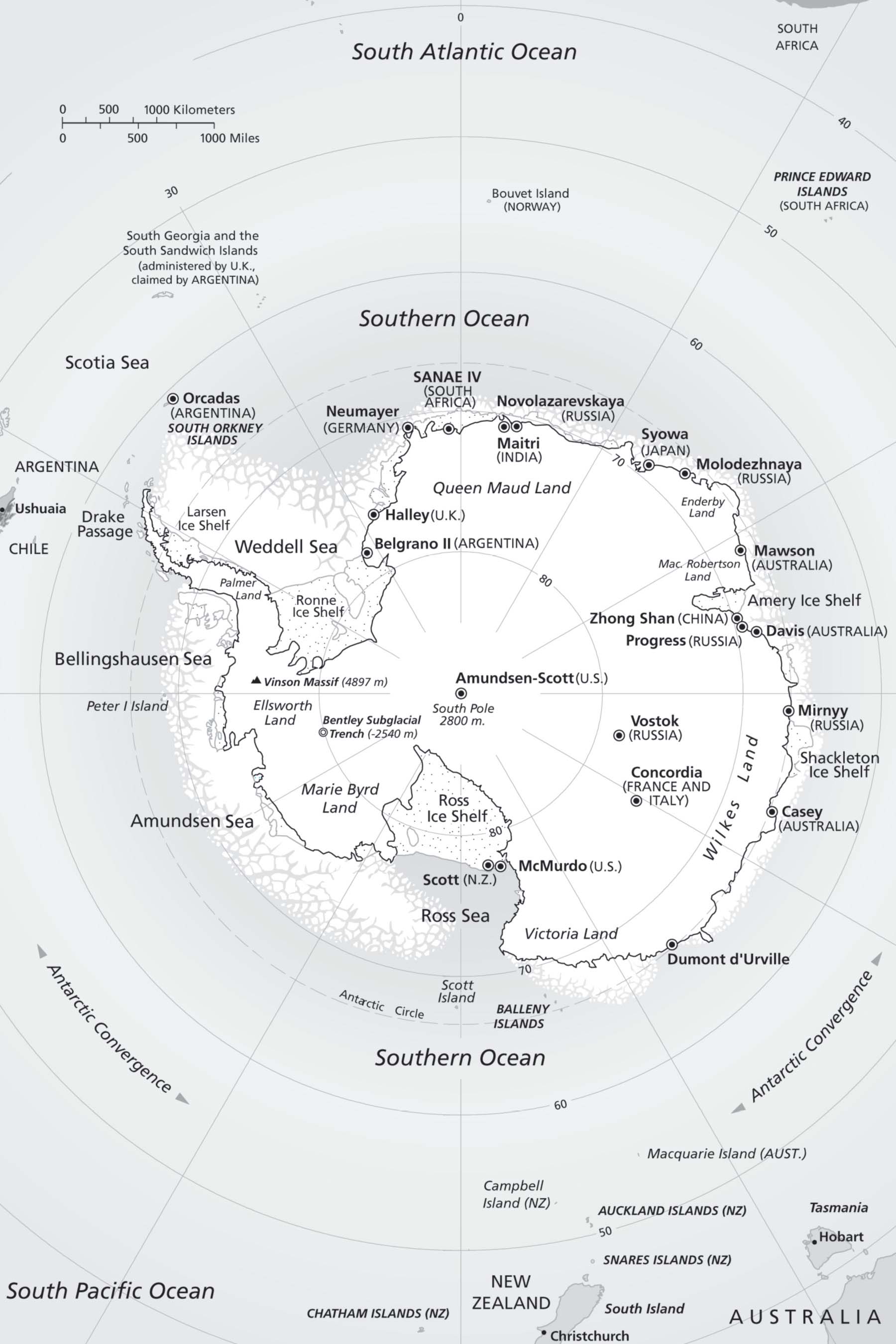

The expedition was assembled on King George Island, one hundred miles off the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. From there we shuttled man, gear, and thirty-six sled dogs south on six Twin Otter flights, to our starting point on the Larsen A Ice Shelf. I was on the second flight with Jean-Louis and my team of ten dogs.

Once we lifted off and cleared the mountains of KGI, the yellow light of midwinter filtered through the windows and shimmered on the dogs hair. The vibrations of the twin engines calmed the dogs excitement and put most of them to sleep. Out the foggy window I caught my first sight of Antarctica; in the far distance I could just make out the ice-capped mountains of the Antarctic Peninsula rising out of the ocean.

But the massive continent seemed somehow out of place. I had expected to see the Antarctica surrounded by sea ice. Instead, rather than being a sea filled with ice, the ocean was wide open, filled with blue waves, void of even the smallest iceberg. We approached the Peninsula from the west, over the Bellinghausen Sea, and then made a crossing over the sheer-faced mountains that make up the narrow backbone of the Peninsula.

Clouds hugged the high peaks, and below them I could see green ice and massive crevasse fields. At nine thousand feet we topped the final mountain range, and in the distance I saw a blue metallic color between the high mountain peaks. To my surprise, the Weddell Sea was also open! Just seventy-five years earlier, the dense pack ice of this sea was strong enough to crush Shackletons ship, Endurance . The area I could see was a mixture of tabular icebergs and open water. When I had researched our route across the Larsen Ice shelf, the scientists had told me about the unusually warm summers on the Peninsula and that they thought these might be the first signs of global warming. I had studied climate all of my life and was well read on the topic. Global warmingan issue with severe implications for our planet and dangerous impacts for our way of lifewas something scientists thought was going to happen generations from now, but it was an instant reality to me when I got my first glimpse of the continent and then the Weddell Sea.

We flew out over the Weddell, which was studded with flat-top tabular icebergs stretching in long lines towards horizon. I was struck by the Larsen Ice Shelfs massiveness. I had never seen anything of such large proportion. Icebergs that had broken off it looked as big as the glaciers lining the continent, ice walls rising a hundred feet above the water. The shelf was enormous and seemed to go on forever southwards.

Looking out the window of the small, vibrating plane, down onto the seemingly infinite ice of the Larsen, I recorded the following in a small cassette player: July 26th, 1989: It is Antarctica, which I am seeing for the first time today, that is going to be the main player in the destiny of the human race. It is this snow and ice. If the atmosphere continues to warm, this ice right in this area is going to break off into the ocean.

At the time it didnt seem possible that an ice mass this large could actually break up; it seemed the Larsen was as permanent as the Antarctic continent itself. But thirteen years later, on March 2, 2002, I was thumbing through the Minneapolis Star Tribune , and on page nine in bold print was a headline that shocked me: Larsen B Ice Shelf Disintegrates. At first I thought it couldnt be true: it seemed like science fiction, and it would take days before I could grasp the extent of this global environmental catastrophe.

There is no way to comprehend the massiveness of the disintegration of the Larsen Ice Shelf unless you have skied and walked across it. In that early winter of 1989, it would take us thirty-one days, from July 27 to August 26, to cross its full length. Every day, camp after camp, through storm, whiteouts and clear weather, we skied and pushed our sleds becoming intimately familiar with the ice shelf that treated us for the most part with safe surface conditions.

After we crossed the Larsen we gained altitude, and for the next six months and 3,400 miles we experienced the coldest conditions imaginable on the planet. Our introduction was two months (sixty consecutive days) of winter storms along the Peninsula. It was only through teamwork and the combined efforts of strength and spirit that we survived. Finally we distanced ourselves from the storms as we rose up to 10,000 feet on the Antarctic Plateau. There the weather was milder, with temperatures moderating to about 20F during the twenty-four-hour light of summer. We reached the South Pole on December 13th, 1989, and then crossed the Area of Inaccessibility on the eastern side of the plateau. On our descent, we again met severe storms as the sobering darkness of our second Antarctic winter returned. We learned not to trust Antarctica, and only sixteen miles from our final destination a polar storm came in from the high plateau. That storm nearly cost us the life of our teammate Keizo Funatsu, who became lost when he went out to feed his dogs, was caught in a huge white-out as the storm intensified, and ended up spending the night alone in the storm, curled up in a ball, blowing snow his only protection.

Next page