The publication of this book was supported, in part, with a generous grant from the Eugenie M. Anderson Women in Public Affairs Fund.

2015 by Cathy de Moll. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical

Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 551021906.

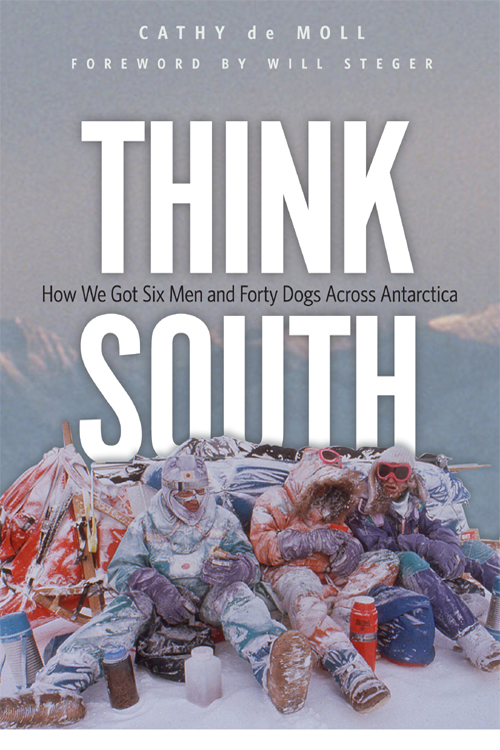

Cover photos and all expedition photos Will Steger

Additional photos and informational web links at

cathydemoll.com/thinksouth

www.mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Manufactured in Canada

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-0-87351-988-5 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-0-87351-989-2 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

To

JESSE, HANS, KINCAID, and LOUDEN,

my Buetow boys, with love and thanks

and to the continent of Antarctica

and all the hope it represents

The International Trans-Antarctica Expedition crosses Antarctica, 198990. Per Breiehagen

Foreword

Sir Ernest Shackleton wrote in his prospectus for the Endurance expedition, There now remains the largest and most striking of all journeysthe crossing of Antarctica. In 1914, he organized an expedition to traverse the continent by dog team on a seventeen-hundred-mile route from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Ice Shelf. Shackletons dream was crushed, however, along with his ship the Endurance , by the moving ice of the Weddell Sea, and what was planned to be the last great polar journey turned out to be the most famous rescue in exploration history.

I read the story in high school and, like many others, I was impressed by the explorers character and leadership. He was my hero of sorts, but I cant say I ever really understood this man until I read the behind-the-scenes account of Shackletons four polar expeditions in the book Shackleton , by Margery and James Fisher. It wasnt really the expeditions I related to, because they were from a different era. What resonated with me was the other half of Shackletons life: the organizational and fundraising efforts that launched these endeavors. Through the Fishers brilliant descriptions of his challenges off the ice, I felt a close kinship to Shackleton and gained a deeper understanding of the explorer. In truth, the logistical and financial challenges of launching a complicated expedition have not changed much. I have lived through similar experiences. But, unfortunately, that part of the story is rarely shared.

This book helps to change that. Think South is the detailed behind-the-scenes recounting of the 19891990 International Trans-Antarctica Expedition, written by its executive director, Cathy de Moll. I consider her to be the seventh member of our team, and this is the other half of our story. Her brilliance and talent made the expedition possible. Ever calm under fire, with dignity and a smiling humor, she somehow broke through the seemingly impossible barriers placed in our path. Using her political skills and financial savvy, she navigated the minefields of international politics and banking, donor relations, vendor problems, and personal relationships. In the pre-Internet era of the telex and the fax, her tight, sharp writing finessed the challenges of international communications, which sometimes seemed as daunting as the expedition itself. This masterful telling of the expeditions story reminds me how much I will always be deeply indebted to her.

Cathys work in running the expeditions business, like the work of the team members during the crossing itself, required finding ways for people from different countries to solve problems. The stories she tells here demonstrate, again and again, that people from vastly different cultures who share good will and a worthwhile goal can find ways to succeed. And thats both a reflection and a demonstration of the expeditions real legacy: our contribution to the protection of Antarctica and to the decision to renew the international Antarctic Treaty.

Destiny may be too strong a word to use, but I always felt that we were chosen for this mission. There was a magic at work from the very first day Trans-Antarctica was conceived in a chance meeting on the chaotic ice in the middle of the Arctic Ocean. I was co-leading a team of eight people and five dog teams in an attempt to achieve what the polar experts considered impossiblethe first unsupported expedition to the North Pole. At the same time, Dr. Jean-Louis Etienne, a French physician, was making a bid to be the first to haul a sled solo to the pole. Leaving from separate locations on the north coast of Canadas Elles-mere Island a month earlier, we both had encountered temperatures down to minus sixty degrees, moving ice, enormous pressure ridges, and open leads of water.

On April 9, 1986, I was leading out, pushing my sled through heavy ice, when suddenly my dogs veered to the right. I looked up and there was a man dressed in blue on top of a pressure ridge. I walked up to him and inquired, Jean-Louis? He responded in a French accent, Will? In the silence, we embraced. It felt like we were lost brothers meeting for the first time. Soon, the rest of my team surrounded us and we talked briefly in the bitter cold. Jean Louis was dressed lightly, so our conversation soon ended. We agreed to camp beside each other the next day.

The next evening, Jean-Louis entered my tent, where we could share a cup of tea (since we were unsupported, I was not able to accept his hospitality). We compared notes about our expeditions, but soon our conversation shifted to future plans. I had brought a map of Antarctica with me and laid it out on the sleeping bag. I traced my index finger along a red line that I had drawn across the continents longest axis. I told Jean-Louis I wanted to dogsled the longest possible route across Antarctica, a thirty-seven-hundred-mile, ocean-to-ocean traverse. He studied the map with interest and joked, This is a long expedition. You will need a doctor. I told him then and there that I would like to do this expedition with him. We both agreed that our North Pole journeys were personal bests and recognized that our success, if it happened, would open the door to projects that would otherwise be out of reach.

The upcoming international review and reaffirmation of the existing Antarctic Treaty gave us a chance to link an expedition with something that was important to us. In 195758, sixty-seven nations had participated in the unprecedented International Geophysical Year, during which scientists collaborated worldwide in eleven earth sciences, including precision mapping, meteorology, seismology, oceanography, and more. At the end of the experiment, the twelve nations that had been active in Antarctica formed a treaty to preserve it as a continent of science, belonging to no individual country. The treaty, signed in 1959 and entered into force in 1961, called for rule by consensus, no military weapons or activity, and the sharing of all research for at least thirty years. The treaty did not, however, protect the minerals that lay below the miles of ice or address the recently discovered ozone hole above it.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.