Christopher Isherwood - Where Joy Resides

Here you can read online Christopher Isherwood - Where Joy Resides full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Where Joy Resides

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Where Joy Resides: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Where Joy Resides" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Christopher Isherwood: author's other books

Who wrote Where Joy Resides? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Where Joy Resides — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Where Joy Resides" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

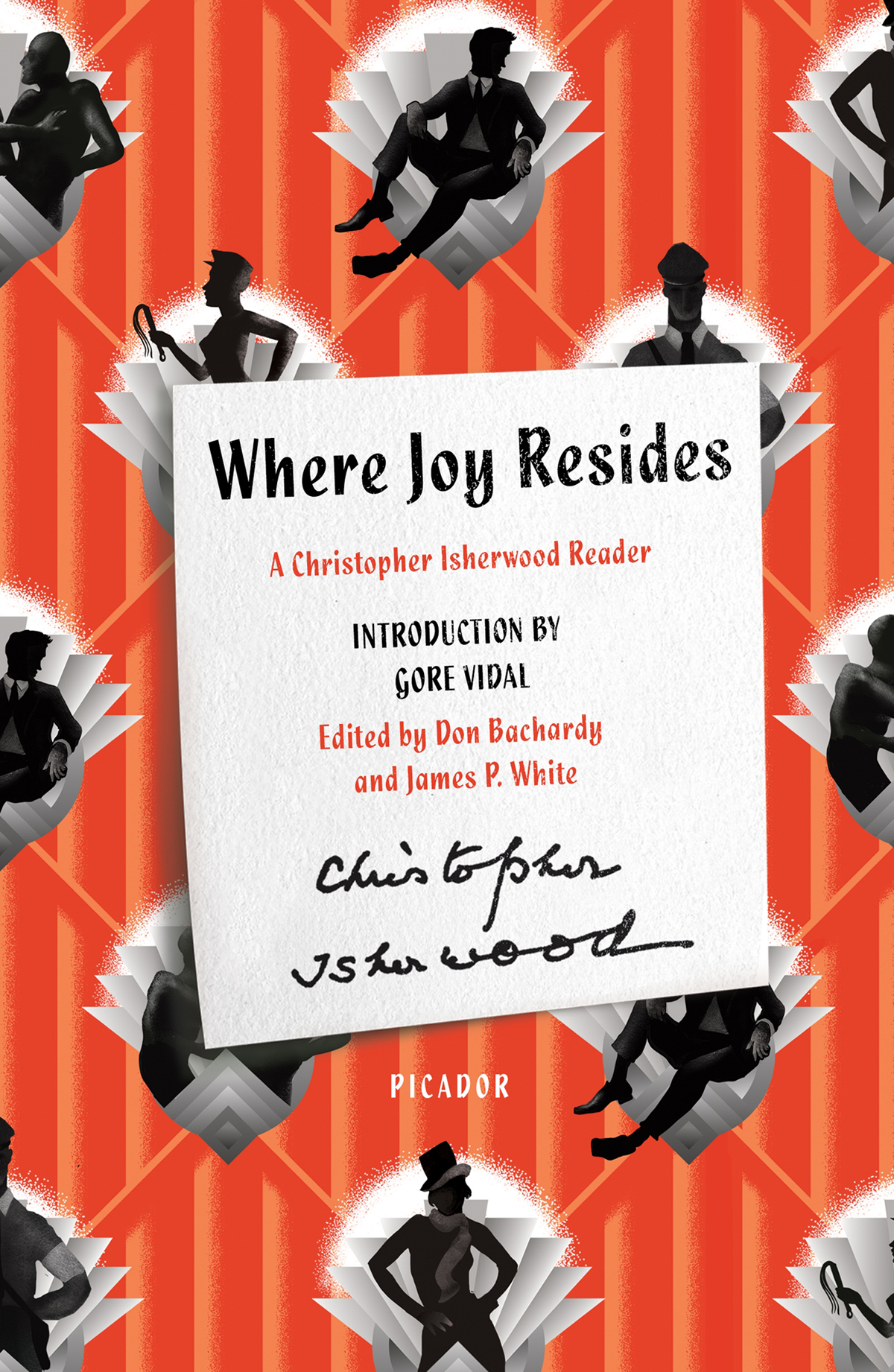

A Christopher Isherwood Reader edited by Don Bachardy and James P. White with an introduction by Gore Vidal

Picador

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

New York

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

And the true realism, always and everywhere, is that of the poets: to find out where joy resides, and give it a voice For to miss the joy is to miss all.

From The Lantern-Bearers by Robert Louis Stevenson, as quoted by Christopher Isherwood in his commonplace book

IN 1954 I HAD LUNCH with Christopher Isherwood at MGM. He told me that he had just written a film for Lana Turner. The subject? Diane de Poitiers. When I laughed, he shook his head. Lana can do it, he said grimly. Later, as we walked about the lot and I told him that I hoped to get a job as a writer at the studio since I could no longer live on my royalties as a novelist (and would not teach), Christopher gave me as melancholy a look as those brighteven harshblue eyes could affect. Dont, he said with great intensity, posing against the train beneath whose wheels Greta Garbo as Anna Karenina made her last dive, become a hack like me. But we both knew that this was play-acting. Like his friend Aldous Huxley (like William Faulkner and many others), he had been able to write to order for movies while never ceasing to do his own work in his own way. Those whom Hollywood destroyed were never worth saving. Not only had Isherwood written successfully for the camera, he had been, notoriously, in his true art, the camera.

I am a camera. With those four words at the beginning of the novel Goodbye to Berlin (1939), Christopher Isherwood became famous. Because of those four words he has been written of (and sometimes written off) as a naturalistic writer, a recorder of surfaces, a film director manqu. Although it is true that, up to a point, Isherwood often appears to be recording perhaps too impartially the lights, the shadows, the lions that come within the area of his vision, he is never without surprises; in the course of what looks to be an undemanding narrative, the author will suddenly produce a Polaroid shot of the reader reading, an alarming effect achieved by the sly use of the second person pronoun. You never know quite where you stand in relation to an Isherwood work.

During the half century that Christopher Isherwood was more or less at the center of Anglo-American literature, he has been much scrutinized by friends, acquaintances, purveyors of book-chat. As memoirs and biographies now accumulate, Isherwood keeps cropping up as a principal figure, and if he does not always seem in character, it is because he is not an easy character to fix upon the page. Also, he has so beautifully invented himself in the Berlin stories, Lions and Shadows, Down There on a Visit, and Christopher and His Kind, that anyone who wants to re-reveal him has his work cut out for him. After all, nothing is harder to reflect than a mirror.

To date, the best-developed portrait of Isherwood occurs in Stephen Spenders autobiography, World Within World (1951). Like Isherwood, Spender was a part of that upper-middle-class generation which came of age just after World War I. For the lucky few able to go to the right schools and universities, postwar England was still a small and self-contained society where everyone knew everyone else: an extension of school. But something disagreeable had happened at school just before the Isherwoods and Spenders came on stage. World War I had killed off the better part of a generation of graduates, and among the graduated dead was Isherwoods father. There was a long shadow over the young of dead fathers, brothers; also of dead or dying attitudes. Rebellion was in the air. New things were promised.

In every generation there are certain figures who are who they are at an early age: stars in ovo. People want to know them; imitate them; destroy them. Isherwood was such a creature and Stephen Spender fell under his spell even before they met.

At nineteen Spender was an undergraduate at Oxford; another undergraduate was the twenty-one-year-old W. H. Auden. Isherwood himself (three years Audens senior) was already out in the world; he had got himself sent down from Cambridge by sending up a written examination. He had deliberately broken out of the safe, cozy university world, and the brilliant but cautious Auden revered him. Spender writes how, according to Auden, [Isherwood] held no opinions whatever about anything. He was wholly and simply interested in people. He did not like or dislike them, judge them favorably or unfavorably. He simply regarded them as material for his Work. At the same time, he was the Critic in whom Auden had absolute trust. If Isherwood disliked a poem, Auden destroyed it without demur.

Auden was not above torturing the young Spender: Auden withheld the privilege of meeting Isherwood from me. Writing twenty years later, Spender cannot resist adding, Isherwood was not famous at this time. He had published one novel, All the Conspirators, for which he had received an advance of 30 from his publishers, and which had been not very favorably reviewed. But Isherwood was already a legend, as Spender concedes, and worldly success has nothing to do with legends. Eventually Auden brought them together. Spender was not disappointed:

He simplified all the problems which entangled me, merely by describing his own life and his own attitudes towards these things. Isherwood had a peculiarity of being attractively disgusted and amiably bitter. But there was a positive as well as negative side to his beliefs. He spoke of being Cured and Saved with as much intensity as any Salvationist.

In The Whispering Gallery, the publisher and critic John Lehmann describes his first meeting with Spender in 1930 and how he talked a great deal about Auden, who shared (and indeed had inspired) so many of his views, and also about a certain young novelist called Christopher Isherwood, who, he told me, had settled in Berlin in stark poverty and was an even greater rebel against the England we lived in than he was. When Lehmann went to work for Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press, he got them to publish Isherwoods second novel, The Memorial.

Lehmann noted that the generations Novelist was

much shorter than myself, he nevertheless had a power of dominating which small people of outstanding intellectual or imaginative equipment often possess. One of my favourite private fancies has always been that the most ruthless war that underlies our civilized existence is the war between the tall and the short.

Even so, It was impossible not to be drawn to him. And yet for some months after our first meeting our relations remained rather formal: perhaps it was the sense of alarm that seemed to hang in the air when his smile was switched off, a suspicion he seemed to radiate that one might after all be in league with the enemy, a phrase which covered everything he had, with a pure hatred, cut himself off from in English life.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Where Joy Resides»

Look at similar books to Where Joy Resides. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Where Joy Resides and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.