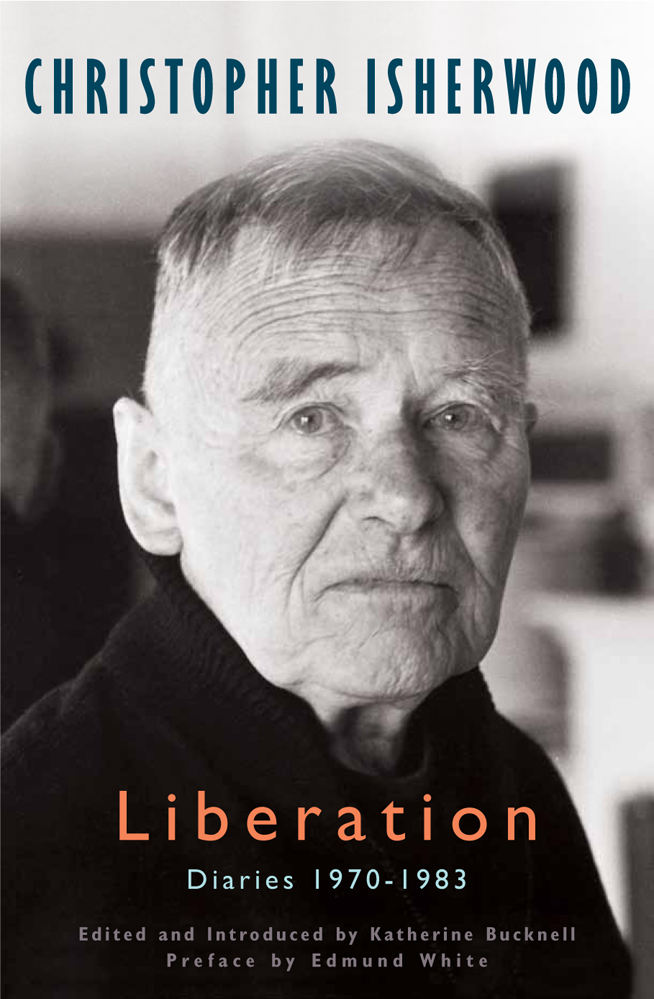

LIBERATION

DIARIES, VOLUME THREE:

19701983

CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD

Edited and Introduced by Katherine Bucknell

Preface by Edmund White

Contents

Readers of novels often fall into the bad habit of being overly exacting about the characters moral flaws. They apply to these fictional beings standards that no one they know in real life could possibly meetnor could they themselves. They condemn a heroine, say, for not facing and condemning her lovers ethical cowardice on some fine point of inner struggle; both her failure and his would scarcely be perceptible in real life. Sometimes it almost feels as if readers, in discussing a book, are showing off, are eager to display a refinement that no one would bother with in the heat of actual experience. In real life everyone is too busy, too submerged in the murk of getting and spending, too greedy to survive and even to prevail to be able to make much out of moral niceties. In any event, friends are always too willing to forgive lapses that they scarcely notice and if they register are sure to share and eager to pardon. Real life is so rough-and-tumble, so clamorous, a bit like an over-amplified rock band on drugs; only in the shaded purlieus of fiction do we catch the tinkling strains of moral elegance coming from another room.

I mention all this because reading the several thousand pages of Isherwoods complete journals is an instructive corrective to the prissiness of reading fiction. Isherwood, whom most of us would consider to be nearly saintly if we knew him personally, had faults that wed say were unforgivable in a novel (he was careful to distance himself from these very faults in his autobiographical fiction). He was seriously anti-Semitic and a year never goes by in his journals that he doesnt attribute an enemys or acquaintances bad behaviour to his Jewishness. I suppose some people would argue that the British gentry are or at least were like that, or that he grew up in another epoch and should not be held to the standards of today. I dont think that that defense quite works. After all, Isherwood lived in Berlin in the late 1920s and early 1930s and experienced first-hand the rise of Hitler to power and witnessed directly the appalling effect of the Nazis on the lives of his Jewish friends. Later he lived in Los Angeles for four decades and worked closely with many Jews; his milieu would never have accepted his anti-Semitism had it been declared. Moreover, he knew perfectly well that every word he wrote, even in these journals, would eventually be published, so one cant even argue that he was simply sounding off in notes not meant for anyone elses eyes.

Then he is a dreadful hypochondriac and in spite of all his much-vaunted spirituality terrified of the least ailment. He worries obsessively about his weight and berates himself when hes a pound or two up on the scale, though he seldom weighs more than 150. He worries constantly (with good reason) about his drinking (I do hate it so, he admits).

And then he can be quite nasty about women friends and their writing. When he travels down to Essex to see Dodie Beesley he reads her novel and says, It is exactly what I feared: one of those patty-paws romances, a little kiss here, a little wistful regret there, one affair is broken off, another starts up. Magazine writing. Whats wrong with it, actually? Its so pleased with itself, so fucking smug, so snugly cunty, the art of women who are delighted with themselves, who indulge themselves and who patronize their men. They know that there is nothing, there can be nothing outside of the furry rim of their cunts and their kitchens, their children and their clubs. Then, in a reversal typical of Isherwood, he writes,... I am indulging in the luxury of being brutal about it because I know I will have to be polite about it to Dodie tomorrowI also know that I shall want to be polite, because I do respect her and she is indeed so much wiser and subtler and better than this silly book.

Oh, yes, hes full of faults and yet I think any fair-minded reader who applies to Isherwood the very approximate demands of life and not the overly exacting standards of fiction will have to admit that he or she has seldom spent so much time with someone so generally admirable. To say so in no way mitigates the obnoxiousness of his real faults. But we should forgive him with the same liberality we apply to ourselves and our friends.

He loves his partner Don Bachardy with a constant devotion that is almost unparalleled in my experience. In the preceding volume, which covered the 1960s, Bachardy was endlessly quarrelsome and difficult. But in this volume, the last, which covers the final decade of Isherwoods life, Bachardy has achieved a measure of worldly success as an artist and has escaped the confines of domesticity enough to enjoy plenty of sexual adventuresenough to catch up with all the sex Isherwood himself had enjoyed in his youth in England, Germany and America. In total contrast to the anger and spite of the 1960s, in this volume Don is endlessly playful and affectionate and kind, and Isherwood (who was thirty years older) is deliriously happy. His main regret about dying is that he must leave Don, though as a Hindu he must have imagined hed join Don in a future life.

After he has lunch with a friend called Bob Regester who is having problems with his lover, Isherwood writes: So of course I handed out lots of admirable advice, which I would do well to follow, myself. Dont try to make the relationship exclusive. Try to make your part of it so special that nobody can interfere with it even if he has an affair with your lover. Remember that physical tenderness is actually more important than the sex act itself. We learn that Chris and Don no longer have sex but that they consider their relationship to be very physical; they sleep together and they are constantly touching each other. At a certain point Chris writes, Im glad people have had crushes on me, glad I used to be cute; it is a very sustaining feeling. I remember the ancient Virgil Thomson once telling me in Key West that he, too, had had a lot of sexual allure and success in his day.

We seldom count a happy marriage as a real accomplishment and yet it so clearly isit is virtually an aesthetic achievement. It requires the same sense of proportion, creativity, empathy, patience, perseverance, equanimity and generosity of spirit as does the making of a novel or play. Isherwoods happy marriage with a tempestuous young man is, unlike the writing of a novel, a collaborative act (in that way its more like preparing a playand not incidentally Chris and Don were constantly working on film and theater scripts together). Anyone who has ever had a happy marriage knows that it is never stable, never finished; it changes every day and is always being created or at least celebrated anew. I suppose in that sense it is like cooking, something that requires a skill that can be acquired over time but that needs to be done every day from scratch. Isherwood understands the vagaries of love better than anyone and he feels (partly to Bachardy but largely to the gods) gratitude , the most appropriate of all the amorous emotions.

Another thing we admire about Isherwood is his seriousness and his curiosity. His reading lists reveal how far-flung his interests are and how deep they go. He is constantly reading demanding books that inform him about every aspect of the world past and present. At one moment, by no means atypical, he is reading Solzhenitsyns The First Circle , Trollopes The Eustace Diamonds and The Autobiography of Malcolm X. His curiosity about the people around him is equally far-reaching. He wants to know what everyone is up to. His old friendsespecially David Hockney, Hockneys erstwhile lover Peter Schlesinger, W.H. Auden, Tony Richardson, his neighbor Jo Masselink, and of course the whole Vedanta crew starting with Swamimake nearly monthly, sometimes weekly or even daily appearances. When Isherwood travels to New York he sees the composer Virgil Thomson and when he goes to England he sees E.M. Forster and the beautiful ballet dancer Wayne Sleep (portrayed in a wonderful canvas by Hockney) and travels north to visit his strange, alcoholic brother Richard.

Next page