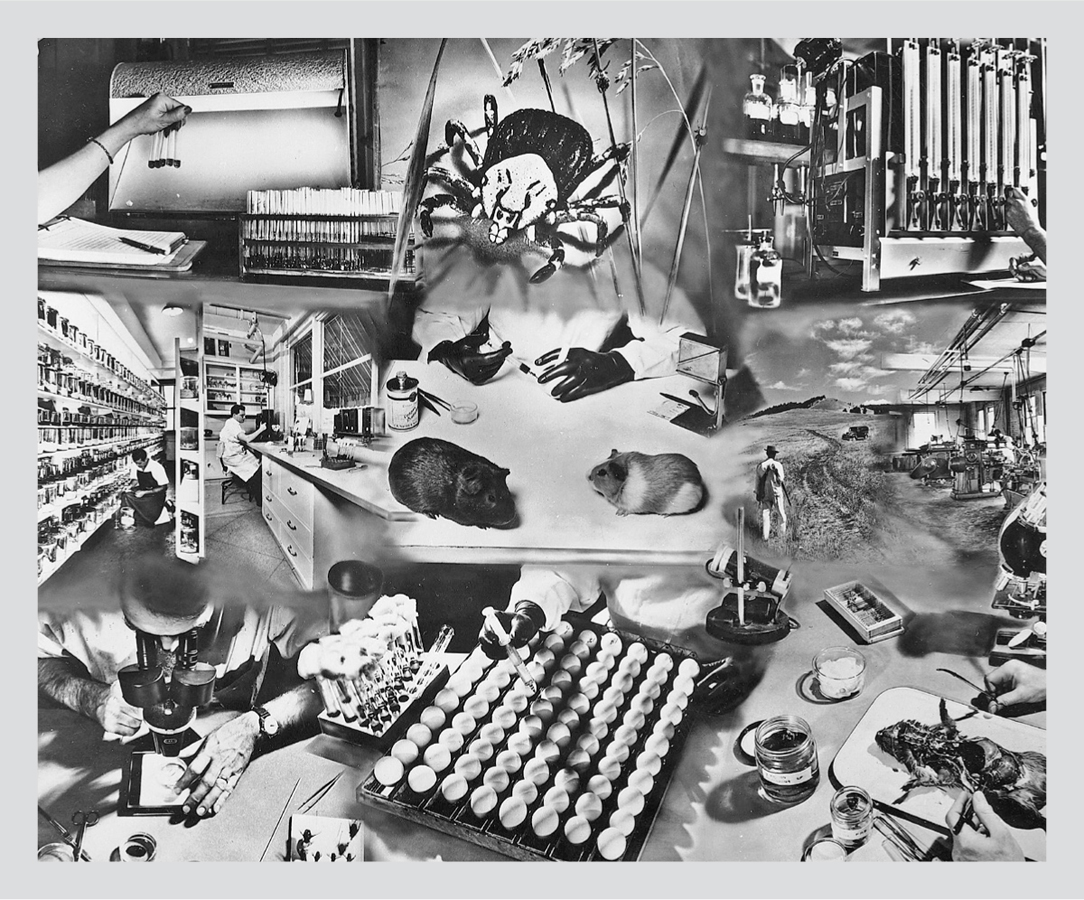

Courtesy of Gary Hettrick, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH)

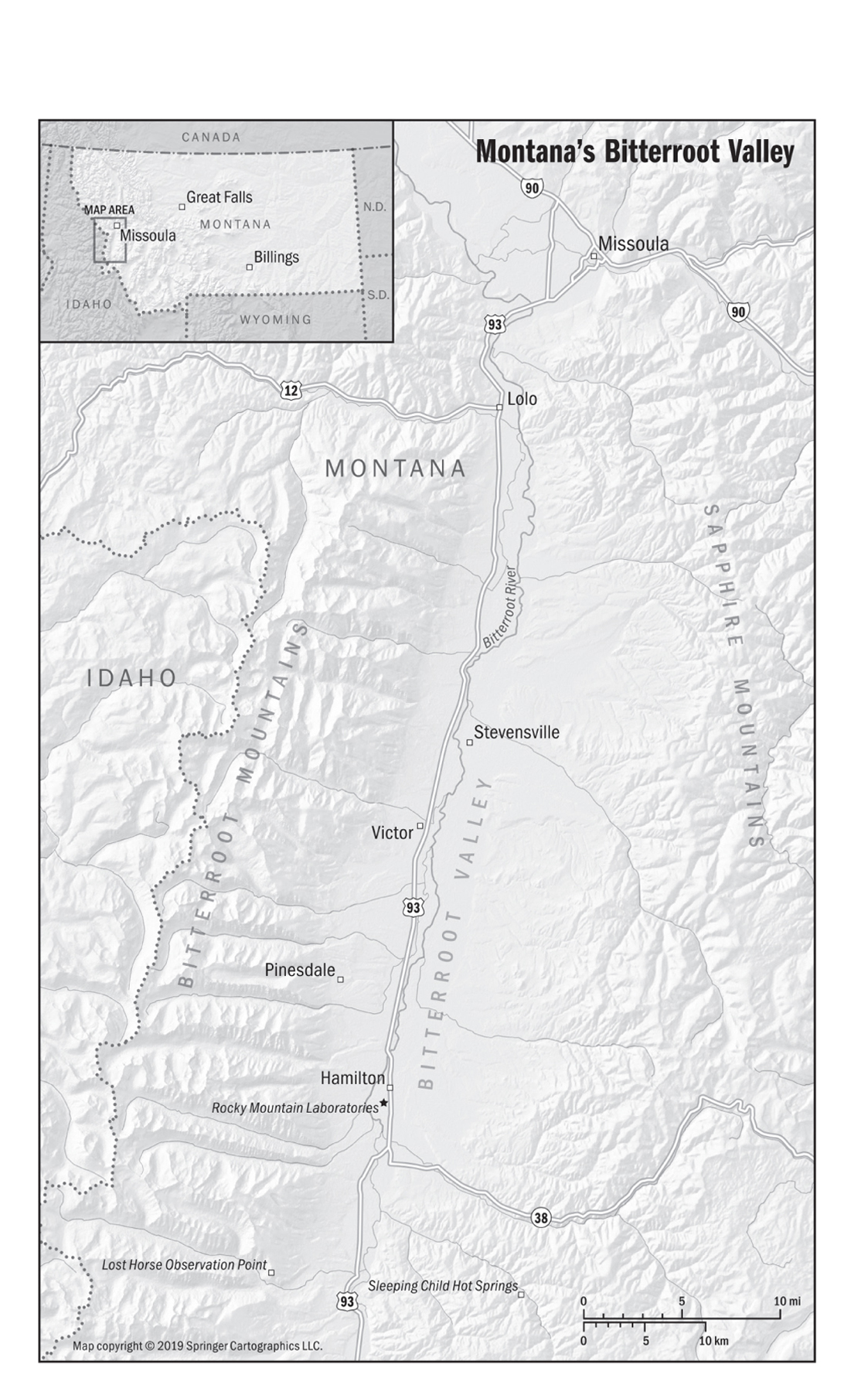

I n 1968 there was a sudden outbreak of three unusual tick-borne diseases that sickened people living around Long Island Sound, an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean off the shores of New York and Connecticut. One of these diseases was Lyme arthritis, first documented near the township of Lyme, Connecticut. The other two were Rocky Mountain spotted fever, a bacterial disease, and babesiosis, a disease caused by a malaria-like parasite.

The investigations into these outbreaks were fragmented among multiple state health departments, universities, and government labs. Its not clear if any officials were looking at the big picture, asking why these strange diseases had appeared seemingly out of nowhere in the same place and at the same time.

Thirteen years later, in 1981, a Swiss American tick expert named Willy Burgdorfer was the first to identify the corkscrew-shaped bacterium that caused the condition that we now call Lyme disease. The discovery made headlines around the world and earned Burgdorfer a place in the medical history books. As researchers the world over rushed back to their laboratories to learn as much as they could about this new organism, the two other disease outbreaks were all but forgotten.

Thirty-eight years later, the conventional medical establishment would like us to believe that it has a solid understanding of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease. It says that the tests to detect Lyme are reliable and that the disease can be cured with a few weeks of antibiotics.

The statistics show a different reality.

Reported cases of Lyme disease have quadrupled in the United States since the 1990s. On average, this means there are about 1,000 new Lyme cases in the United States per day.

While most Lyme disease patients who are diagnosed and treated early can fully recover, 10 to 20 percent suffer from persistent symptoms, some seriously disabling. Patients with lingering symptoms are often dismissed by the medical establishment, a situation that forces them to seek unproven treatments that arent covered by medical insurance. Many are unable to work or go to school. Some go bankrupt. Families break up. Theres a high rate of suicide among Lyme disease patients, reflected in a common saying among the afflicted: Lyme doesnt kill you; it only makes you wish you were dead.

The chasm between what researchers say they know about Lyme disease and what the chronically ill patients say they are experiencing has remained an open wound for decades. This book begins with the premise that both sides are mostly right, and that the main issue is that were viewing this public health crisis too narrowly, through Lyme-colored glasses.

Before I started this book, I thought I had a solid understanding of the Lyme disease problem. As a former Lyme sufferer, I had firsthand experience with the disease, and how the medical system fails patients. As a researcher for the Lyme documentary Under Our Skin, I had investigated the politics, money, and human impact of the disease. And as a writer at a medical school working in a group that teaches scientists how to conduct unbiased research, I was familiar with the fault lines in our current medical system that can compromise scientific objectivity.

It took the late, great Willy Burgdorfer to teach me how to view the problem through a wider lens, through a secret history of the Cold War, when Willy and others turned ticks into weapons of war.

Off Marthas Vineyard, Massachusetts, 2002

Ticks may be a disease-carrying menace for hikers and pets, but theyre also masters of survival: The parasites were sucking the blood of dinosaurs 99 million years ago, according to a set of amber fossils from Myanmar.

Science magazine, December 12, 2017

A tiny eight-legged creature slowly crept up a blade of beach grass. It was about the size of a poppy seed, armored with a hard, shiny shell. When it reached the blades tip, the rear legs clamped down and the creature raised its forelegs high and wide toward the sky. It was blind, and it experienced the world through these forelegs. could detect temperature changes, humidity, ammonia in sweat, and carbon dioxide in breath. The tick was sniffing the air for these signals, waiting for a warm-blooded animal to pass by. It could wait hours, days, or even months, swaying with the sea breeze.

* * *

I climbed out of a cobalt-blue sailboat and onto a misty beach on Nashawena Island, located across the channel from Marthas Vineyard, followed by my husband, Paul, and our two sons, ten and twelve years old. The boys ran off to play in the surf, while Paul and I walked down a sandy path to look around the small island of thirteen square miles, population ten. We saw an old military gun mount and a cowherds cottage, where two rust-colored Scottish Highland cows, dull-eyed and mangy, stood at the edge of a soupy, algae-filled pond.

We walked back to the beach to eat a picnic lunch with the boys, and I looked over at Paul, slim and fit, with big brown eyes and a few strands of silver woven throughout his dark hair. He was as relaxed as Id seen him in a long time. The Silicon Valley start-up where he worked had recently gone public, and we had enough stock options to finally feel some financial relief. We wouldnt have to sweat the monthly cash flow, and probably had enough put aside to cover the boys college tuition. After this vacation, I was going to ramp down my consulting business and try my hand as a full-time writer. Id just won two national writing contests, and the kids were doing well; both were bright, creative, and happy. This would be my shot at doing what I loved most: writing.

* * *

When the carbon dioxide from my breath wafted by, the tick sprang to attention. It began waving its foreleg claws and snagged the skin of the passing mammal. In an instant, the glands below its claws began oozing a fatty, sticky substance that helped it hold on to my leg. Then it started crawling upward, its senses tuned to find a protected, blood-infused patch of skin.

The tick found the perfect spot at the nape of my neck, hidden under my hair. The back legs elevated the ticks mouthparts at the perfect striking angle, and its three-part jaw telescoped down toward my skin. First, its top two cutting mouthparts gently scraped the surface while releasing a numbing agent. Then, by rocking its body back and forth, the tick began digging through my tough outer layer of skin. Its bottom jaw, shaped like a shovel and backed with harpoon barbs, slid into the hole to anchor the drilling operation.

Once a feeding hole was established, the ticks salivary glands secreted chemicals into the wound site. A cement-like substance, coated with a protein that made it invisible to my immune system, hardened into a funnel and anchored the jaws to the hole.

As blood pooled at the bottom of the hole, the ticks throat muscles began a pumping action: saliva flowed out, my blood flowed in. Chemicals in the saliva included a clot-dissolving fluid that kept the wound from scabbing over and others that suppressed my many immune system defenses.

While the tick fed, it released into my bloodstream the microbial hitchhikers floating inside its body. Its salivary chemicals would blunt my immune defenses for a week or more, allowing these foreign invaders to multiply with little resistance.