To Wanda, the only item of essential equipment apart from a Rolex watch (boiled in a stew by Afghans to test its waterproof qualities) not lost, stolen or simply worn out in the course of some thirty years of travel together.

From the reviews of On the Shores of the Mediterranean:

A new book by Eric Newby is something of an event. A superb reporter, Mr Newby paints marvellously detailed portraits. He has an unrivalled eye for the ridiculous and, although this is essentially a serious book, it is frequently very, very funny. He is an extremely elegant writer, beautifully paced and rhythmic For Newby admirers, this particular event is a memorable one, and it should also recruit a lot of new admirers to his ranks

Daily Telegraph

Keeping up with Eric Newby, every breathless puff and pant of it, is worth it all the way. It is a mark of Newbys magnetism that you are so willingly carried along, at such tremendous pace. He takes a deep breath and delivers a massive lungful of history, geography, opinion, experience and sheer fun [He] leaves you gasping in gratitude and wonder

Observer

A splendid book With its generosity, quirkiness, encyclopaedic love of facts, wisdom, humour, sense of history and change, this is a lot more than even the very best of travel books. Its author is a Ulysses, the book an Odyssey

Guardian

Over the years Mr Newby has quite rightly established himself as one of the sharpest, funniest and most boisterously entertaining of all travel writers We find Newby at his incomparable best

Sunday Telegraph

PART ONE

ITALY

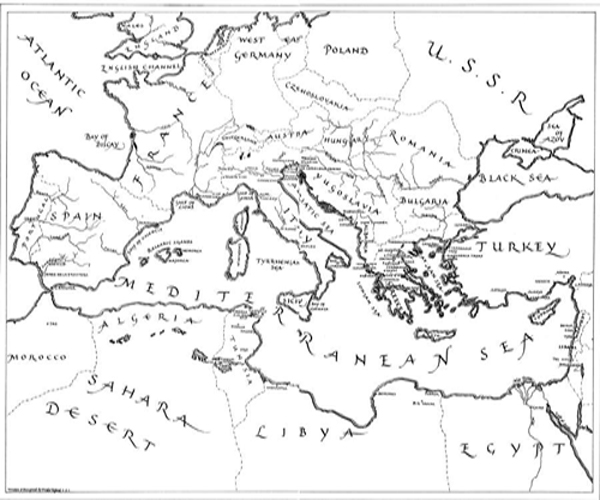

When people in England and America ask about our house in Italy and we tell them that it is in northern Tuscany, their eyes light up, because Tuscany is one of the parts of Italy that the British and the Americans know about, or think they do. For most of them who have visited it, Tuscany conjures up that rather open-cast country permanently suffused in golden light that forms the background of so many fourteenth-century paintings, country in which Chianti is made. In their minds eye they even think they know what sort of house it is we live in, though we stress the fact that it is very small and very ungrand. They immediately begin to think of the sort of house that appears with its name against it on a map, or in an architectural guide to Tuscany as a Villa, followed by the name of its past owner, often a hyphenated one, and that of its present owner, preceded by the word ora, meaning now; for example, to invent one, Villa Grnberg-Tiffany, ora Newby, a place with a spacious terrace and lots of statuary, the sort of place at which Sitwells used to, and Harold Acton still might, drop in uninvited to tea.

In fact our house is in a part of Tuscany so far to the north of Florence, Pisa and Lucca that it ceases to conjure up the idea of Tuscany at all, either in its countryside or in the quality of its light. It is quite near Carrara, a place famous for its marble, where Michelangelo had enormous blocks of the stuff quarried, as did later Henry Moore and Noguchi; marble that is still used to make the sort of tombstones that are popular with the Mafia and the Camorra, the other criminal secret society. Carrara, probably because of the abundance of blasting material conveniently to hand, is also the headquarters of the Italian Anarchists and the place where they hold, or used to until recently nothing is for ever their annual convention. The house certainly cannot be called a villa, or even a weekend villetta, let alone a Villa-whatever-it-was, ora Newby. Looking down on it from the upper part of our vineyard it resembles a dun, a prehistoric Irish fort, more than a dwelling, or else one of those enormous heaps of stone that people in limestone countries used to pile up in the process of making a field, before the coming of the bulldozer, which is what a lot of old peasant houses do look like in the Mediterranean lands. It does in fact appear as a small black blip on a sheet of the Italian 1:25,000 military maps, which look as if they had been drawn by a lot of centipedes with ink on their feet.

One of the reasons we had bought it was because it was exactly like almost any one of the various houses in which Italian peasants had hidden me high up in the Apennines in the winter of 19434 when I had been an escaped prisoner-of-war. It was in autumn 1943 that, emerging from my prison camp in the valley of the River Po, I had first met my wife, who lived in the nearby village and who had arranged for me, because I had a broken ankle, to be hidden in the maternity ward of the local hospital. Later, I had been recaptured and sent to Germany, but when I was finally released in 1945 I had gone back to Italy, and Wanda and I had subsequently married. And we still are married.

The house is in a little dell, and although it is hidden from almost every other point by the chestnuts, i castagni, from which it takes its name, and by olive trees and vineyards, it has a magnificent view over the valley in which the Magra, one of Italys polluted rivers, flows into the Ligurian Sea, one of the numerous more or less polluted seas into which the Mediterranean is sub-divided.

We found the keys, all five of them, where our neighbours had hidden them in case we arrived late at night, as like many of the older country people, they went to bed as soon as it was dark and they had eaten their evening meal, which was what most country people did before the arrival of television. Three of the keys are very big, all of them are very old and shiny. On the first day the house became ours some twenty years ago I lost one of the big ones, a key that had been made when the house was built more than a hundred years before, and I never found it again. Luckily there was a spare key, but that was the only one. The doors of the house are made of slabs of chestnut cut by hand, and they are so full of cracks and holes that from the inside you can see the light of day shining through them in dozens of places. When I lose the rest of the keys, or if the huge locks give up, it will mean new doors, and the house will never look the same again.

With the doors open I switched on the current and turned the water on at the tap outside the bathroom; the water comes from a spring higher up the hill called la Contessa and is very good. The bathroom is in what had been the stalla, the byre in which the animals were kept, on the ground floor below the hay loft, and this means that when we want to visit it in the night from our bedroom, which is upstairs, we have to go down the staircase which leads to it. The staircase is in the open air, which is why visitors are provided with chamber pots in which they occasionally put their feet when getting out of bed in the darkness, with spectacular results.

Apart from some dust and fallen plaster and a few dead mice, there was nothing much wrong. Here, the mice are almost as big as rats. This time they had eaten the poison laid down for them the previous winter instead of our bedding, as they often do, gnawing their way through the backs of old chests-of-drawers to get at it, although one or two of them had taken some chunks out of a red shirt of mine from L. L. Bean, Freeport, Maine, to make what we subsequently found when we discovered one of their nests, to be blankets for their children.