I would like to thank Lucinda McNeile, Sarah Hodgson and Tamsin Miller at HarperCollins; Philip Lewis, the designer, and my granddaughter, Lucia Ashmore, for their work on the book.

In a Surrey lane aged about three and a half having suffered a mishap.

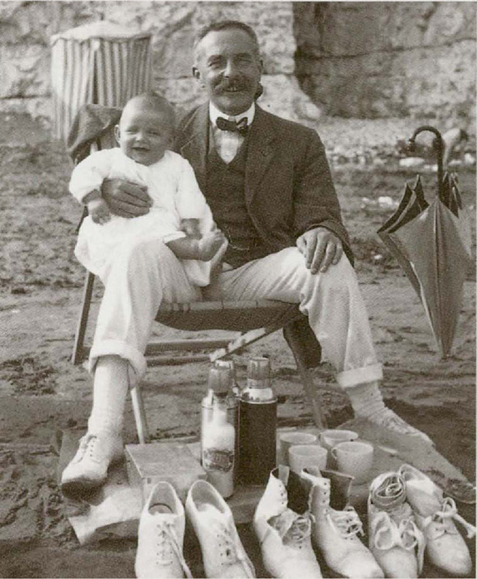

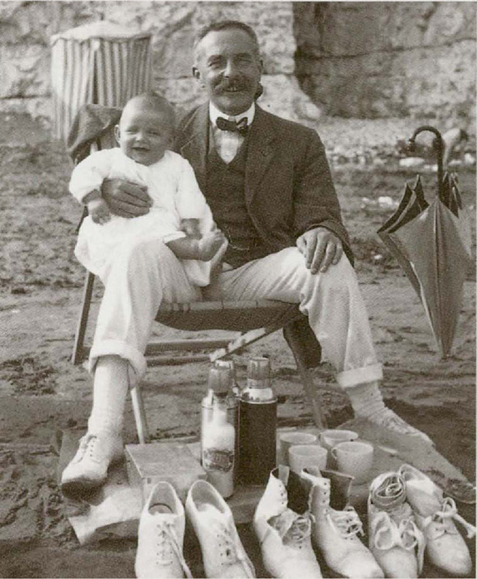

Myself and Father, somewhere on the South Coast, c. 1920

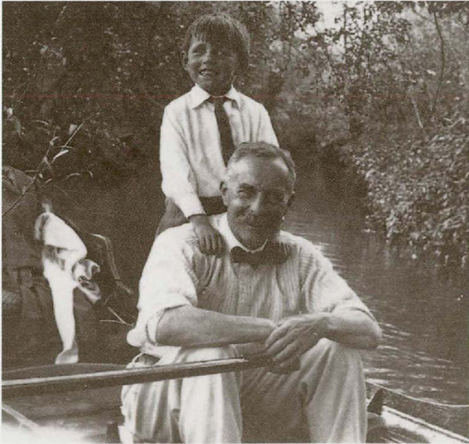

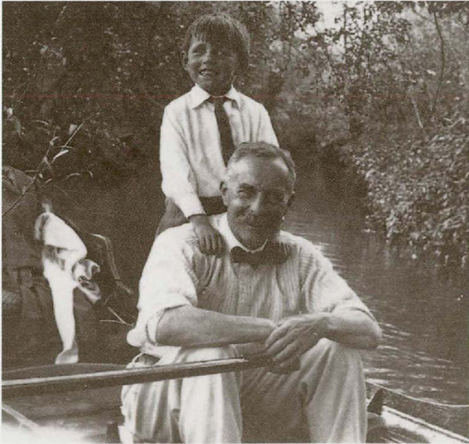

In a Thames backwater with my father, aged about seven.

T o have reached the age of eighty years more or less unscathed is by no means une affaire mince, an insignificant matter, which is how a French friend of more or less the same age described it. How I contrived to reach sixty and then seventy without noticing it is still a mystery to me. When I was young, sixty-five was the age when bank managers (a species now becoming extinct) used to retire. They were good, clean living chaps who, in the not too distant past had played cricket and rugger on Saturdays against teams from other banks. This was the moment when, having arrived at the age of sixty-five, they were given gold watches, and in the nicest possible way told to make themselves scarce (otherwise given the chop). It was said, and widely believed, that within a year of receiving their awards and marching orders many of them would be dead. But being eighty-eight plus is a different matter (mince) altogether. This is the time when sprightly septuagenarians start giving up their seats to us eighty-year-olds on public transport and those who bid us mind how you go! really mean it.

What was I doing when I passed through a number of valleys of death unscathed? I am still trying to remember what I was up to all those years, when I could have been the recipient of a gold watch, if I had been a bank manager. Some of the time I must have been managing something myself something I have never been conspicuously good at.

Only recently have I begun to appreciate the fascination my father must have felt when he himself was well over eighty and met a gentleman who had presented him with a visiting card on which were embossed the words Mr Thos. W. Bowler, followed by an address in Walton-on-Thames which conjured up visions of a rather fine riverside house. To which my father had added the following codicil in neat pencil: Met on train. The originator of the Bowler Hat? Like a man of the Renaissance my father was constantly being overcome by the wonders of the world in which he lived. Walking down a street he would suddenly glimpse some odd cloud formation, or a man with a goitrous protuberance, and without warning would stop in his tracks in order to enjoy the sight more closely.

As a result the simplest excursion made by our family resembled an extended streetfighting patrol in hostile territory, its members taking up entire streets.

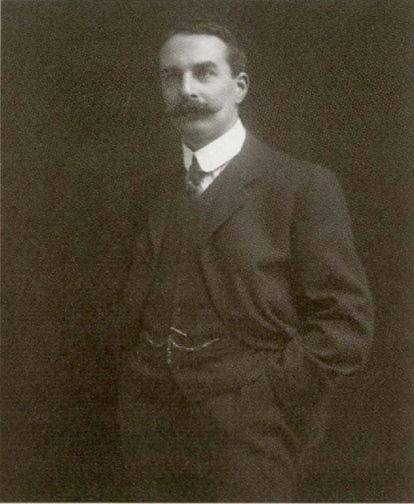

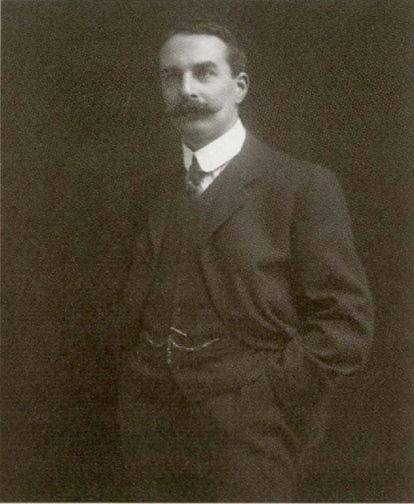

My father, unknown date

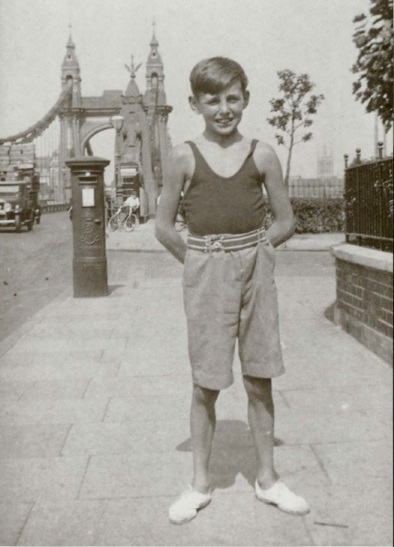

Castelnau Mansions, Barnes, SW13. The flats in which I was born by Hammersmith Bridge.

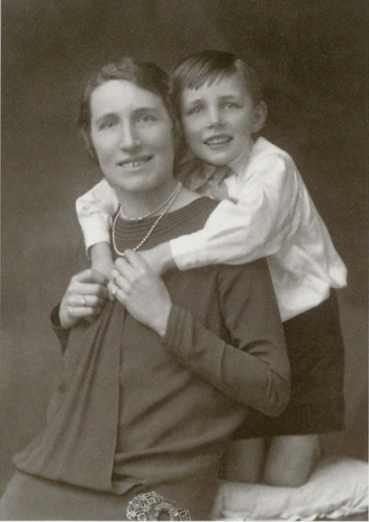

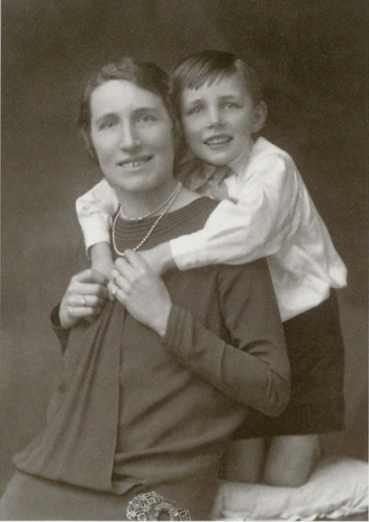

With my mother, aged eight

My upbringing was Victorian. My father, when he was at home, strict. If I didnt eat my greens (and I really hated them) at lunchtime on Sundays, they would appear again, cold for tea. I grew up with a strong constitution my father saw that as an aid to victory my bowels were kept open and my nasal passages unclogged. I was forced to sniff salt water up my nose, and to take plenty of cold baths as an aid against filthy thoughts it doesnt work.

His ambition was that I should win the Diamond Sculls at Henley. I didnt. But I did learn to scull stylishly, as did my mother, in our sumptuous double-sculling skiff which was big enough to sleep three people. My mother was very much younger than my father. She had been a model girl in my fathers fashion business, and still accompanied him when he travelled, which was often.

It was also inculcated in me that work was important and that it was slightly wrong to enjoy oneself, although it didnt inhibit my father, mother and me from doing so.

It was not my father who dinned into me The Importance of Success in Business, but my odious uncle my fathers brother. He was the managing director of a large department store. His Christmas present to me, when I was about ten, was a book Lessons of a Selfmade Merchant to his Son (exhortations on how to do down the opposition and short change the customers). I told him what I had done when I put it in a wastepaper basket.

With a school friend going camping in Surrey, 1934

With my parents and an uncle and aunt on a South Coast beach

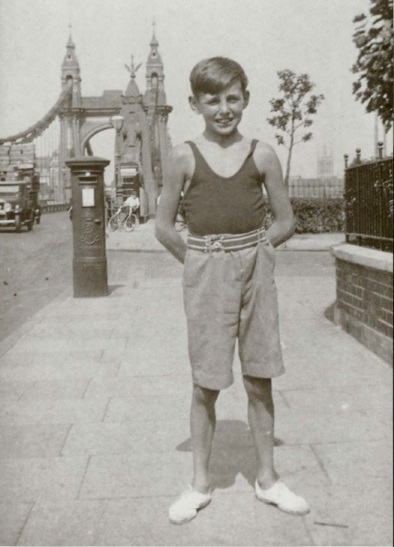

By Hammersmith Bridge, outside our flat

At this time I experienced a great feeling of inferiority at my inability to cope with problems of a mathematical nature which had to be solved algebraically. At that time (in the 1930s) a pass in Mathematics was obligatory. In spite of being good in History and English, I failed Mathematics. I was sixteen so my father took me away from St Pauls and put me into a fashionable advertising agency in W1. Two years later I left it to go to sea.

It is the sea that has influenced me most, although I am no great sailor, an oarsman more than a mariner. Introduce me to a sailing ship sailor who hasnt been influenced by it. There is nothing more unpredictable than a sailing ship, engineless, at the mercy of the winds and currents. And there were times when the ship would show her different faces: when she was running with 63,000 sacks of grain under the hatches, or utterly becalmed in an oily sea with turtles sunbathing around her. Then there was the sound of the storm in the rigging, nothing more awesome in all the world, and going aloft in it and working the winches and grinding away at the capstans; and hearing but not seeing whales surfacing around the ship in dense fog. And St Elmos fire (the corposants) running along the steelyards until they seemed to be ablaze.