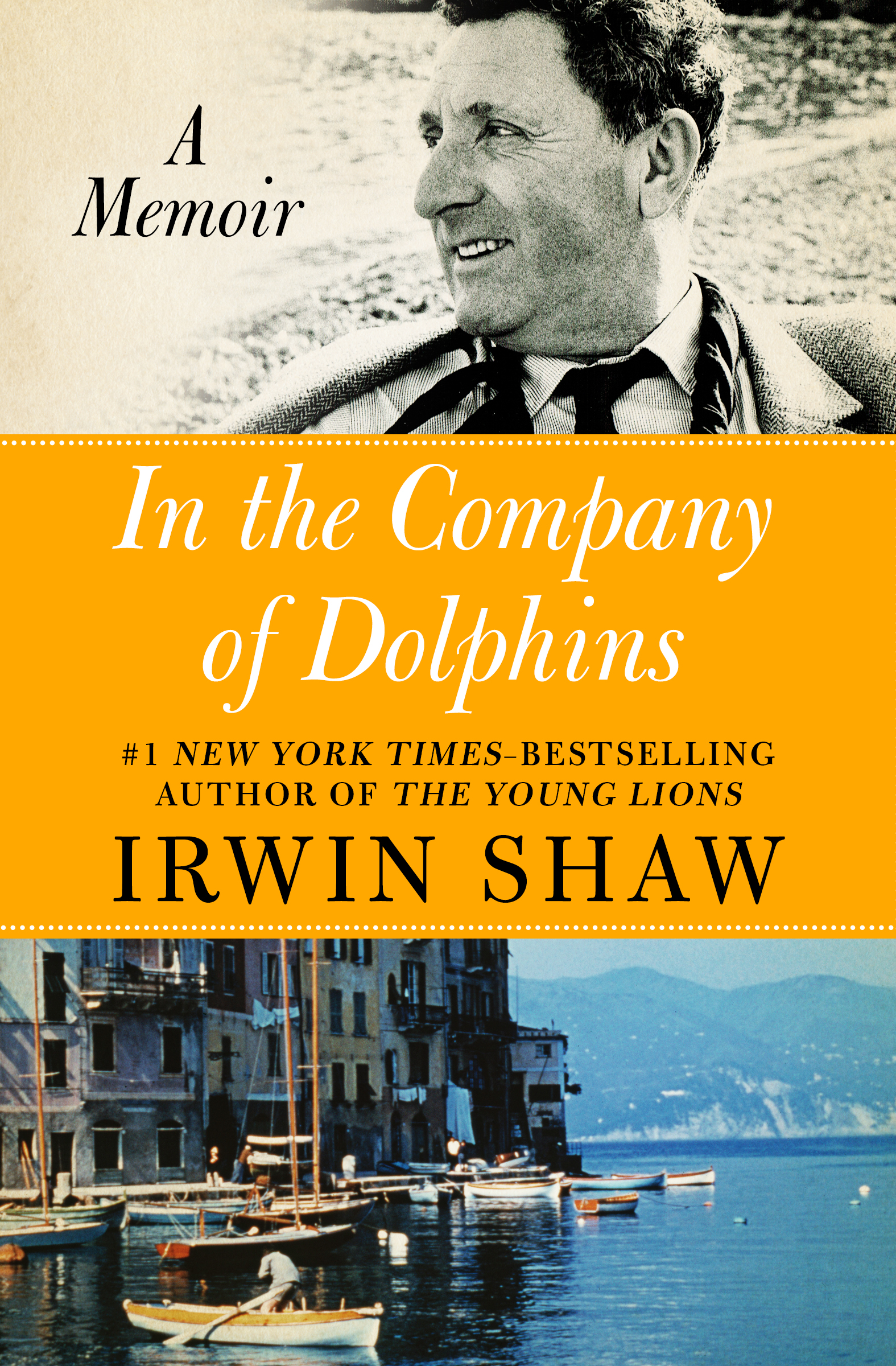

In the Company of Dolpins

A Memoir

Irwin Shaw

To the memory of Ted Patrick

PORTS OF CALL

I

SHEEPSHEAD BAY

When I was a boy I lived near Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn. At that time, there were a good many private boats moored in the secure, narrow harbor. There was also a training stable for the horses of the New York City mounted police nearby, and my childhood dream was twofoldto own my own horse and to cruise the seas on my own yacht. The horse was to be a thoroughbred, more or less on the lines of Man OWar, the yacht was to be long, trim, nautically palatial. Decades later, when I lived for awhile on the edge of the Pacific in California, I owned a horse for eight months or so. He was wind-broken and after fifty yards his breath sounded like an express train in a tunnel; he shied at flying bits of paper and stumbled on even ground and trampled my feet when I put the bridle on him, but he was a horse and he was my own and I experienced a childish delight galloping him along the hard sand on the waters edge. He cost me fifty dollars, but he was worth every cent of it. Recently, with Sheepshead Bay many years behind me, I cruised four seas on a yacht that, for six weeks at least, was more or less my own. It was no palace, and it was rented, or chartered, as they say in yachting circles, and it cost a good deal more than fifty dollars, but the pleasure I had in it at certain moments lived up to the dreams of the boy wandering along the wooden docks of distant Brooklyn.

It is one of the quirks of our age to believe that when desires like these are fulfilled, they finish by leaving a taste of ashes in the mouth. That is, the young man who has his heart set on having a movie star as his mistress is supposed after awhile to discover that it was not worth the trouble, that he is stuck with an annoying and unpleasant female who makes his life miserable. The man who slaves to accumulate a great fortune and high political power is supposed to be left disgusted and unhappy as he contemplates the evidence of wealth and potency he has accumulated. The young writer or scientist who dreams of gaining the Nobel Prize, in this view of things, is cynically disdainful of it when he gets it. The truth very often, I have found, is simpler than that. The young man is enchanted with his movie star. The rich man revels in his wealth and uses his power with ever-renewed delight. I am not on good terms with many winners of the Nobel Prize, but from what I have seen, they would rather have won it than not.

So with my dreams of fair boats, warm waters and foreign coasts. The envy I nursed in my heart for the salt water plutocrats of Sheepshead Bay proved, after four decades, to have been justified, and the pleasures I imagined them enjoying on their graceful craft turned out to be real. In this age of massed holidays, congested roads, transistor-noise, jet-speed, fumes and telephones, one feels a timeless exaltation on the deck of a boat chugging through blue water at eight knots, swept by the tonic wind, the small white ship splendid and solitary in the clean shining circle of the Mediterranean horizon.

Looking at maps is one of the most satisfactory of occupations. Some of the purest joys of the voyage came months before I set foot on board the ship, when, on winter evenings, I studied a large map of Italy which generously included the coast of France from Toulon east and threw in the entire coast of Yugoslavia for good measure. The trip was to take us from St. Tropez to Venice, a voyage calculated to satisfy, for one summer, at least, the pent-up passion for distant harbors of even the most ardent of Sheepshead Bay mariners. It was to last six weeks, and I meant it to be a long, rejuvenating escape from private cares and public insanities. The schedule of arrivals and departures was so crowded that I felt I was assured of being places just long enough to enjoy their beauties without having the time to be oppressed by their problems.

While I was unpracticed in the art of cruising, I was not completely uninformed about the dangers that might arise. I had many friends who had sailed and steamed for pleasure and from their experiences I had been warned about certain hazards. The chief hazard, it appeared, was The Other Couple, or The Other Couples. Wind and tide had done in comparatively few of my friends, but Other Couples had brought disaster almost every time. The Other Couple might be composed of your lifelong buddy and his best wife, or the most amusing woman in Europe and her charming husbandbut, somehow, after two or three weeks of visiting some of the gayest and prettiest places in the world, in the most perfect summer weather, I was assured that the ship would put into port with its passengers brimming with mutual hatred, or, even worse, congealed in polite but awful boredom.

The reason for inviting The Other Couple or The Two Other Couples on board is usually a simple oneMoney. Chartering a boat is expensive, and unless you are ready to go without tobacco and other luxuries for the rest of the year, dividing the cost seems like the most sensible plan to follow. But a vacation that ends in gloom and recrimination is expensive at any price, and I resolved to keep the passenger list down to myself, my wife, and my son, since, in an approximate way, we have proved over the years that we could live with each other under a great variety of circumstances, and we agreed that we most probably could survive a further six weeks in each others company. Holiday Magazine obligingly offered to play, at least financially, the role of The Other Couple, without actually having any of its officers filling any of the cabins or trying to tell the Captain what port to put into next.

Still, it is not as easy as one might think to stick to a resolution to stay alone, with ones family, on a yacht. Once it is known that you have rented a boat, there is a general feeling among your friends that you will invite them to share your joy for long periods at a time. In the circles in which we move, at least, it is almost inconceivable that any family would choose, out of its own free will, to remain locked almost exclusively in each others company for six weeks at a time. Not wanting to appear hopelessly eccentric in the eyes of my friends, I invited quite a few of them to join us for different legs of the voyage, but cunningly asked them to meet us at times when I knew they would not be free and at places which I knew they could not reach. The only exception was a lady whom we have known so long and so well that we could treat her, without offense, as badly as any other member of the family, and who, besides, plays excellent tennis and could be depended upon to hold her end up staunchly in any game we managed to rustle up in our travels. And even she was not to meet us until Dubrovnik, two weeks before the end of the voyage.

GARE DE LYON

We started from the Gare de Lyon in Paris. This was several years ago and Paris was still rumbling with the uneasy repercussions of the unsuccessful putsch of the Generals, but the platform of Le Train Bleu, against all the dictates of geography, somehow was removed from all that. As you passed the gate you had a foot already in the blissful South and had entered a season in which people did not think of uprisings or wars. Startlingly shaped girls in slacks and sandals boarded the train with self-satisfied looking gentlemen who were obviously not their husbands, young men hurried past carrying water masks and flippers and spearguns, tennis rackets were tossed through windows, and many of the passengers were already bronzed, as though they had prepared conscientiously for the sun of the Midi which was to greet them in the morning.