Pagebreaks of the print version

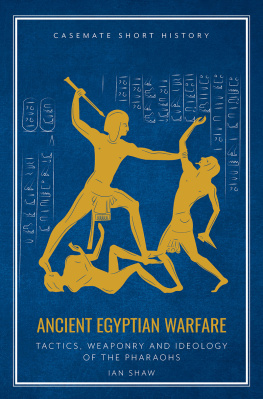

Casemate Short History

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN WARFARE

TACTICS, WEAPONS AND IDEOLOGY OF THE PHARAOHS

Ian Shaw

Oxford & Philadelphia

Published in Great Britain and

the United States of America in 2019 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

Casemate Publishers 2019

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-7250

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-7267

Kindle Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-7267

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All line drawings and photographs are Ian Shaws unless stated otherwise.

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

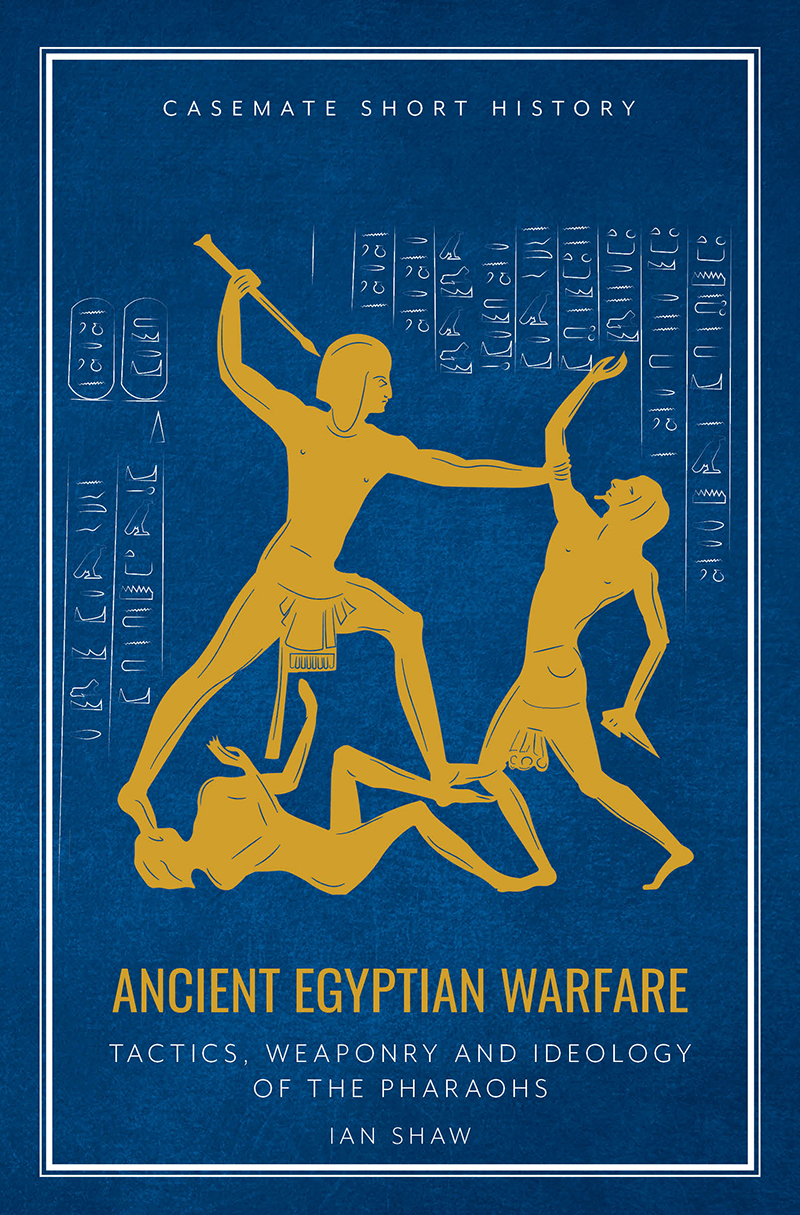

Part of a row of Asiatic captives, depicted in the Temple of Amun at Karnak, taking the form of foreign place-names inscribed inside cartouche-style citywall ideograms, each symbolizing a defeated Syro-Palestinian city state, 18th Dynasty, c.15501400 BC.

INTRODUCTION

A WIDE VARIETY OF APPROACHES HAVE been taken to the study of Egyptian warfare, ranging from the analysis of battle tactics to the cataloguing of types of physical injury. The excellent preservation of military equipment, such as bows, axes and chariots, has provided the basis for numerous detailed discussions of the changing nature of Egyptian military technology. However, most analyses of ancient Egyptian warfare have tended to focus on a variety of more abstract areas such as political history, military strategy, symbolism, and the topography and ethnography of the ancient world, often steering away from the practical questions of life, death and survival on the battlefield. This situation is exacerbated by the inclination of many of the ancient textual and artistic sources to present battles not as historical events but as aspects of the myth and symbolism of the king and the gods.

Researchers have only rarely focused on the practical experiences of the individual Egyptian soldiers on the battlefield. addresses this issue, discussing firstly the official Egyptian view of battle and then the much more difficult topic of the roles, attitudes and physical and mental experiences of individual Egyptian soldiers. Since much of the analysis is based on pictorial and textual evidence, the discussion inevitably deals as much with the aims and purpose of the documents and images themselves as with the elusive underlying reality of Egyptian battle.

Typically, many aspects of daily life that were portrayed on the walls of Egyptian tombs such as agriculture or craftwork have survived to some extent in the archaeological record at the sites of ancient towns and villages. Battle scenes are very occasionally portrayed in tombs, and quite frequently portrayed on the walls ), but relatively few corresponding archaeological traces have survived. The battlefield is among the most transient and ephemeral of man-made features, and even the most famous battles of medieval and post-medieval Europe have often proved difficult to locate and explore precisely through archaeology. In Egypt, although the arid climate has helped to preserve both battle-scarred human remains and weaponry, the actual landscapes in which conflicts took place have proved much more difficult to identify.

The earliest anthropological evidence for battle in Egypt takes the form of a Palaeolithic mass-grave of hunter-gatherers (mostly killed by flint-tipped arrows) at the site of Jebel Sahaba, in modern Sudan. Nine thousand years later, at the end of the 3rd millennium BC, at least sixty Middle Kingdom soldiers were buried in a mass-grave near the tomb of the 11th-Dynasty ruler Nebhepetra Mentuhotep II ( c .20552004 BC) in western Thebes, many having died from severe head wounds probably incurred in the course of siege warfare. Physical evidence of this type is an invaluable means of verifying and complementing the details of the surviving textual and pictorial descriptions of Egyptian battle. These anthropological and medical data are discussed in .

In the late Predynastic and the early pharaonic period ( c. 3200 2900 BC), the main sources for Egyptian warfare take the form of images and ideogrammatic proto-texts that are mostly carved on ceremonial and votive artefacts, such as knife-handles, cosmetic palettes, mace-heads and bone and ivory labels (see ). The reliefs on these artefacts are characterized by constantly repeated motifs: the king smiting foreigners, the siege and capture of fortified settlements, the binding and execution of prisoners, and the offering of the spoils of war to the gods. These have been interpreted in a variety of ways by scholars, but the general consensus is that they may often refer to generic aspects of warfare and hostility rather than to actual battles that took place at specific times and places.

Later visual and textual sources include tomb paintings and massive temple reliefs depicting campaigns and battles, as well as victory stelae and the funerary biographies of such key military personalities as the 11th-Dynasty general Intef ( c .2030 BC) and the early New Kingdom admiral Ahmose, son of Ibana ( c .15501500 BC). All of these were relatively public displays of the Egyptian view of battle; just as the works of Classical historians and biographers were written with particular aims and readers in mind, so the pharaonic descriptions of war and battle had their own agenda, and any study must be sensitive not only to content but also to the nuances of literary and artistic forms. If the paintings and reliefs depicting Egyptian battles are to be understood properly, their physical and cultural contexts must also be taken into account. There are clearly two major sources of information: a number of private tombs, at Deshasha, Saqqara, Beni Hasan and Thebes, dating to the late Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom ( c .23451782 BC) and the temple reliefs of the Ramesside period ( c .12931070 BC) at Thebes and numerous sites in Nubia, of which the most important group are those devoted to the battle of Qadesh (see Chapter 3). This battle took place in the fifth year of the reign of Ramesses II ( c .1274 BC). Tremendous publicity was given to the Qadesh conflict, which was depicted on no fewer than five of Ramesses IIs most important temples (Luxor, Karnak, Abu Simbel, Abydos and the Ramesseum), while the literary account has also been preserved on three papyri. Although the scale of the commemoration implies that it was intended to be regarded as a high point in Ramesses reign, it seems likely that it was at best a case of stalemate, and at worst a severe setback to Ramesses empire-building.

The reliefs and inscriptions relating to New Kingdom warfare were mostly parts of the decoration of tombs or cult and mortuary temples; they were therefore inextricably linked with the funerary and religious cults themselves. The common placement of battle reliefs in full view on the exterior walls of temples seems to make it clear that at least one of the aims of these monuments was to express ideology relating to power and violence, particularly in relation to the elite culture surrounding the Egyptian king. Indeed, it is worth noting that, whereas in modern times warfare and battle are primarily regarded as destructive and abhorrent aspects of life and society, in ancient Egypt such violence was regarded not only as an essential element of kingship but also as a positive and stabilizing aspect of the role played by the king in ensuring the presence and maintenance of maat (a very specific Egyptian concept relating to truth and harmony) in society. The ideological purpose of the pharaoh was to maintain the stability of the universe; he was thus obliged to fight battles on behalf of the gods and then to bring back prisoners and booty as votive offerings for their temples.