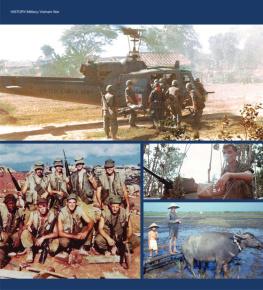

Few, like Jim Parker, saw the second Indochina War from start to finish. And few are qualified to conclude that even though we lost, we did the right thing by coming here to fight. For those who did, thats the wars lasting legacy.

C OL . H ARRY G. S UMMERS J R .

Editor, Vietnam magazine

An enlightening story Few others shared Parkers perspective on the war, and none has reported it quite the same way.

James E. Parker Jr. has written a thoroughly honest and compelling memoir. Last Man Out is his unpretentious account of an American everymans extraordinary service to his country throughout the Vietnam War, a tale told with humility and humor and packed with history and heroism. Refreshingly free of cynicism, self-pity, and self-aggrandizement, Parkers candid account of the human dimension of combat belongs on your bookshelf next to Moore and Galloways We Were Soldiers Once and Young.

C OL . J OSEPH T. C OX

Author of The Written Wars: Americas War Prose Through the Civil War

Parker is no run-of-the-mill war memoirist but a skilled storyteller with a knack for weaving quick tales with revealing punch lines. He introduces a memorable cast of supporting characters.

A Ballantine Book

Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group

Copyright 1996 by James E. Parker Jr.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by The Ballantine Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in a slightly different form by John Culler & Sons in 1996.

Ballantine and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

www.randomhouse.com/BB/

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00-190008

eISBN: 978-0-307-48697-4

v3.1

We all went to Gettysburg, the summer of 63:

Some of us came back from there

And thats all,

Except the details.

Capt. Praxiteles Swan, Confederate Army,

Complete Account of the Battle of Gettysburg

Contents

ONE

Army Recruit

Cottonpicker didnt think it was a big deal. This was Christmas 1963, and I was home from college. We were sitting on his back porch drinking beer.

You dont die if you quit college, he said. We aint talking about the future of the world here.

Donald Lawrence, dubbed Cottonpicker by my father several years before, was my best friend while I was growing up. A big, brawny redhead, he was a paratrooper sergeant in the 82d Airborne Division at Fort Bragg Army Base near my hometown of Southern Pines, North Carolina, and lived with his wife and children in an apartment behind my house. During my early teen years, we had spent many late afternoon hours tinkering with his old car under a nearby magnolia tree. On weekends, we had hunted and fished deep in the woods of the Fort Bragg reservation. He taught me how to stalk deer and gig frogs and light a cigarette in the wind and cuss like a soldier. He had always done most of the talking when we were together. Im da Chief and you da Indian, was his way of putting it. I was used to taking his advice, so I listened carefully.

Youre what now, twenty-one? If you want to quit college and raise hell, well thats all right, I reckon. Its your life. Just dont go feeling guilty about it. Tell people, I aint getting nothing out of college and what I want to do is get out there and holler, so get outa my way. He paused. But, you know, you might want to have some plans, Jimmy. I just want to raise hell dont feed the dog.

He looked at me and smiled in that lopsided fashion of his.

The Army aint bad. Been good by me.

My father had suggested that I stay in college while I was making up my mind about my future because it was a better environment for decision makingmore educated counselors, better choices. I had already dropped out once for a semester.

If you drop out again, he reasoned, youll never go back. You are the family namesake. You have an obligation here.

When I returned to the University of North Carolina (UNC) after Christmas, I tried to study, but I just wasnt interested. And I felt alone. My friends had dropped out. That left me, along with maybe twenty thousand strangers at Chapel Hill, reading The Organization Man and in danger of becoming one.

I would sit at my desk in the dorm, a book open in front of me, and stare out the window, bored. I had always been more restless than my friends. As a kid, Id stop and watch a train go byor even a Greyhound buswanting to be on it, getting on down the road. The journey had seemed as important as the destination.

My home was on the western edge of Fort Bragg. From a big tree in my front yard, I used to watch U.S. Air Force planes in the distance and daydream about flying those planes or jumping out of them. Cottonpicker had taught me the eight jump commands. Standing on a lower limb of the tree, I would recite, Get ready. Stand up. Hook up. Check equipment. Check buddys equipment. Sound off for equipment check. Stand in the door. Go! I would jump to the ground and do the parachute landing fall (PLF), just as Cottonpicker had taught me. Id climb back up the tree and fantasize about life as a soldier or a world traveler.

Those thoughts might have passed in time and I might have had a more normal adolescence and a less troubling college experience if I hadnt taken a trip during the summer of 1957, between my freshman and sophomore years of high school, that forever changed my life. My parents had sent me to Mars Hill College, my fathers alma mater, to take college-level summer courses in hopes of jump-starting my interest in academics. Instead, I made friends there with a rowdy group of college sophomores. Two were from Cuba, one from Lake Wales, Florida, and one from Wilson, North Carolina. At the end of summer school, we developed an elaborate ruse to excuse my absence from home for a few days. My friend from Wilson and I then thumbed to Florida and went to Havana, Cuba. Three days and two nights there in the tenderloin area near the harborneon lights flickering off a Cuban bar at three oclock in the morning, rumba music coursing the air, cigar smoke, fights, whores, rum were exactly what I had dreamed about in that tree in my front yard. I hated to leave, but we ran out of money. With a revolution going on in the hills, there were restrictions on just hanging around.

My parents were happy to see me when I arrived home, but in short order they sent me to a military school. That was a radical decision for them. They had grown up on farms in North Carolina and thought that only uncontrollably spoiled kids in California went to private military schools. They found it hard to believe that their son, raised in the rural heartland of the South, required special education, but they saw that unusual glint in my eye, the Cottonpicker influence, my total lack of interest in their goals, my trip to Cuba. I needed an attitude adjustment.

ONE

ONE