Contents

Guide

OUR MAN DOWN IN HAVANA

The Story Behind Graham Greenes Cold War Spy Novel

CHRISTOPHER HULL

O UR M AN D OWN IN H AVANA

Pegasus Books Ltd

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Christopher Hull

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition March 2019

Interior design by Sabrina Plomitallo-Gonzlez, Pegasus Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-018-7

ISBN: 978-1-64313-101-6 (ebk.)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

In remembrance of:

My father Oswald Hull (19192007): geographer, historian

My student Emma Galton (19942018): bright sunflower

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

G raham Greene later confessed that a sense of mischief and irresponsibility had stirred in him. Maybe a U.S. immigration official roused his renowned anti-Americanism with the question Ever been a member of the Communist Party? While he could not have anticipated that a student prank at twenty years old would provoke immigration problems three decades later, the well-traveled British writer surely knew a candid answer would cause trouble. His four-week membership of the party at Oxford in 1925 had unintended consequences, as would this encounter with overzealous officialdom at San Juan Airport in 1954.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Joseph McCarthys anticommunist paranoia stoked hot the temperature of the Cold War. The Republican senator was engaged in a high-profile witch hunt to drag out alleged reds from under many beds in the United States. For example, the House of Representatives Un-American Activities Committee summoned scores of writers, film directors, and actors from the U.S. entertainment industry to appear and face an Are you now or have you ever... ? line of questioning.

Following Greenes affirmative reply to U.S. Immigration in Puerto Rico, they deported him to Haiti and onward to Cuba, an unplanned visit just ten days after an uneventful one-night stay. His eye-opening return to Havana inspired him to resurrect a decade-old outline for an espionage story, originally set in Estonia before the Second World War. In fact, an unintended consequence of his 1954 deportation was one of his most iconic novels, set in the Caribbean fleshpot where every vice was permissible and every trade possible.

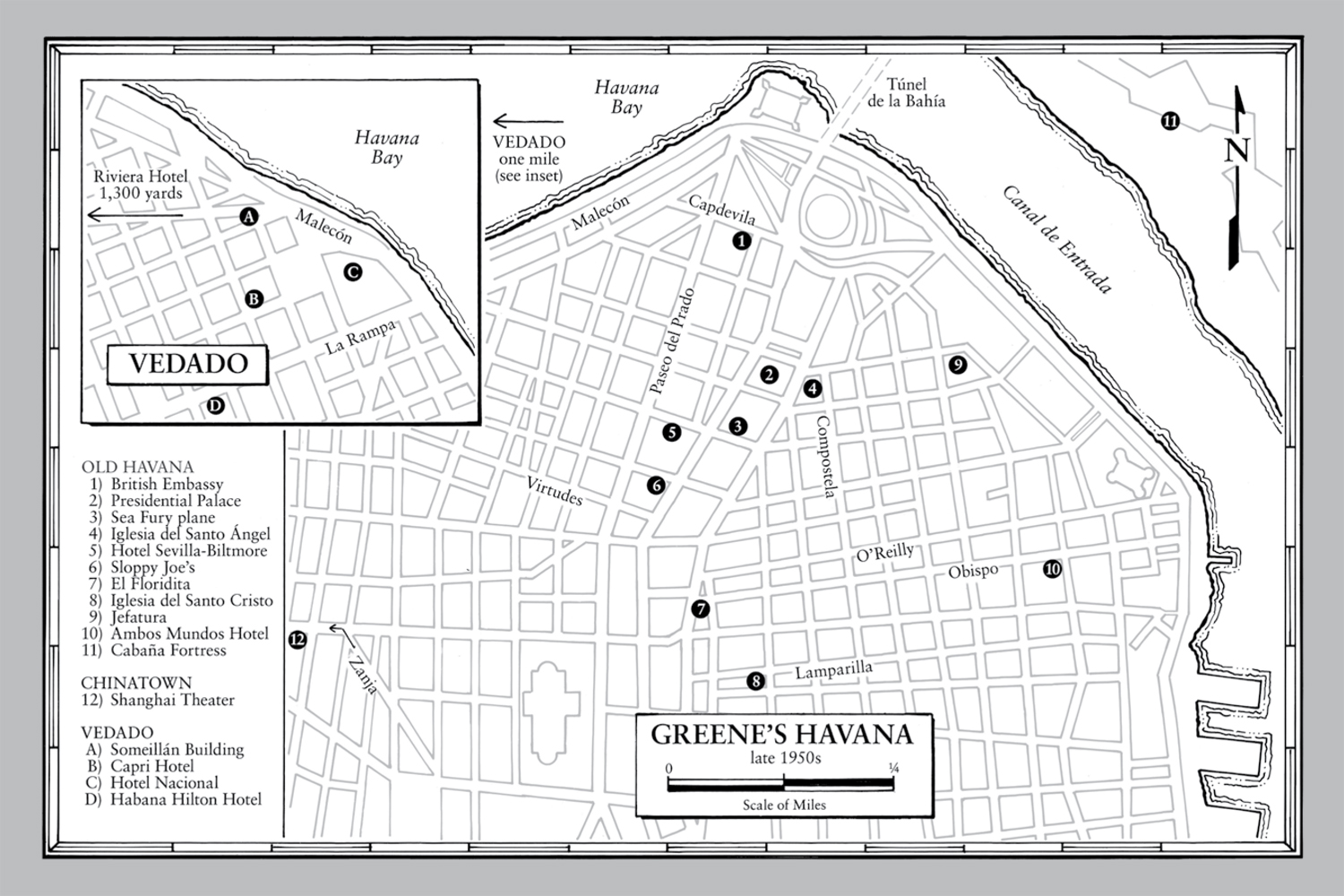

The spy fiction satire Our Man in Havana hit bookshops in early October 1958, just twelve weeks before Fidel Castro led his bearded rebels to victory in the Cuban Revolution on January 1, 1959. The our man of the novel is James Wormold, an expatriate vacuum cleaner salesman living in Havana, recruited by the British Secret Service for their Caribbean network. He invents subagents and intelligence in order to increase his remuneration and fund his spoiled daughters extravagant tastes. One bogus subagent flies over the snow-covered mountains of Cuba in an attempt to obtain photographic evidence of strange constructions. His Secret Service superiors in London swallow his phony reports of military installations, and the sense of farce increases.

Greenes fictional account of invented intelligence not only encapsulated the periods tension and East-West paranoia but also accomplished something far more fascinating. It managed to presage in an almost psychic manner the Cold Wars most perilous event: the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Much like his writing contemporary Ian Fleming, Greene knew the political and espionage worlds he portrayed extremely well. Both Greene and Fleming had worked for British intelligence during the Second World War. In the 1950s, they both introduced MI6 (the Secret Intelligence Service, or SIS) agents as main protagonists in new novels at the height of the Cold War. The two authors both named their fictional spies James and gave each a Double 0 code name. Ian Flemings agent was the suave James Bond, 007, who led a glamorous lifestyle and enjoyed multiple sexual liaisons with attractive women, many of them fellow spies. Beginning with his first appearance in 1953s Casino Royale , which kicked off a long series of novels, Bond drove a Bentley (among other classic British cars) and drank shaken not stirred martinis.

Graham Greenes fictional protagonist, on the other hand, is the austere James Wormold, agent 59200/5. British intelligence services employ him as their man in Havana, where he has lived alone with his teenage daughter, Milly, since his American wife abandoned them. He has a limp, drives an ancient Hillman, and his only extravagance is the frozen daiquiri he drinks at a street bar every morning with his German friend Dr. Hasselbacher. Meanwhile, the local police captain, a sadistic torturer on the payroll of the islands ruthless dictator, is trying to seduce Wormolds sixteen-year-old convent-school daughter. Plain James Wormold was the antithesis of debonair James Bond.

Wormolds spy persona owed something to Greenes own Second World War experience in the Secret Intelligence Service, first in the forlorn outpost of Freetown in Sierra Leone, and later at a Mayfair desk working under notorious Soviet mole Kim Philby. Greene later drew on episodes from his SIS work and the impending Cold War in his espionage fiction.

The odd-sounding name Wormold mimicked the name of one of his romantic rivals, Brian Wormald. The former Anglican priest competed with him for the attentions of Catherine Walston, Greenes American-born goddaughter and his mistress between 1946 and the late 1950s. The name itself conveys the decay and disorientation of an old worm, a moldy worm, or the worm (aka spy) that turned. Although in the case of the Cambridge Spiesmost notorious among them Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, and Donald Macleantheir turning by the NKVD (Soviet secret police agency, forerunner of the KGB) occurred before the British government recruited them to work at its heart: in the Foreign Office, the Security Service (MI5, responsible for intelligence within the UK), and the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS/MI6, responsible for intelligence outside the UK).

Ian Flemings James Bond caught the attention of the mass reading public; his series of novels later turned into a successful and continuing film franchise. Our Man in Havana would find a film life as well. Just six months after publication, film director Carol Reed and screenwriter Graham Greene arrived in post-revolutionary Havana to shoot a black-and-white adaptation of the novel. This was the same directing/screenwriting partnership behind The Third Man , the critically acclaimed 1949 film set in postwar Vienna. Famed for its resonant zither music score and a memorable performance from Orson Welles, The Third Man was a classic of film noir. Despite the star billing of British actors Alec Guinness and Nol Coward, the Reed/Greene collaboration Our Man in Havana failed to command anything approaching the same critical reception or attention. Both works excel, however, in evoking the atmosphere of time and place: the postwar ruins of Vienna, and the pre-revolutionary decadence of Havana.