Contents

Page List

Guide

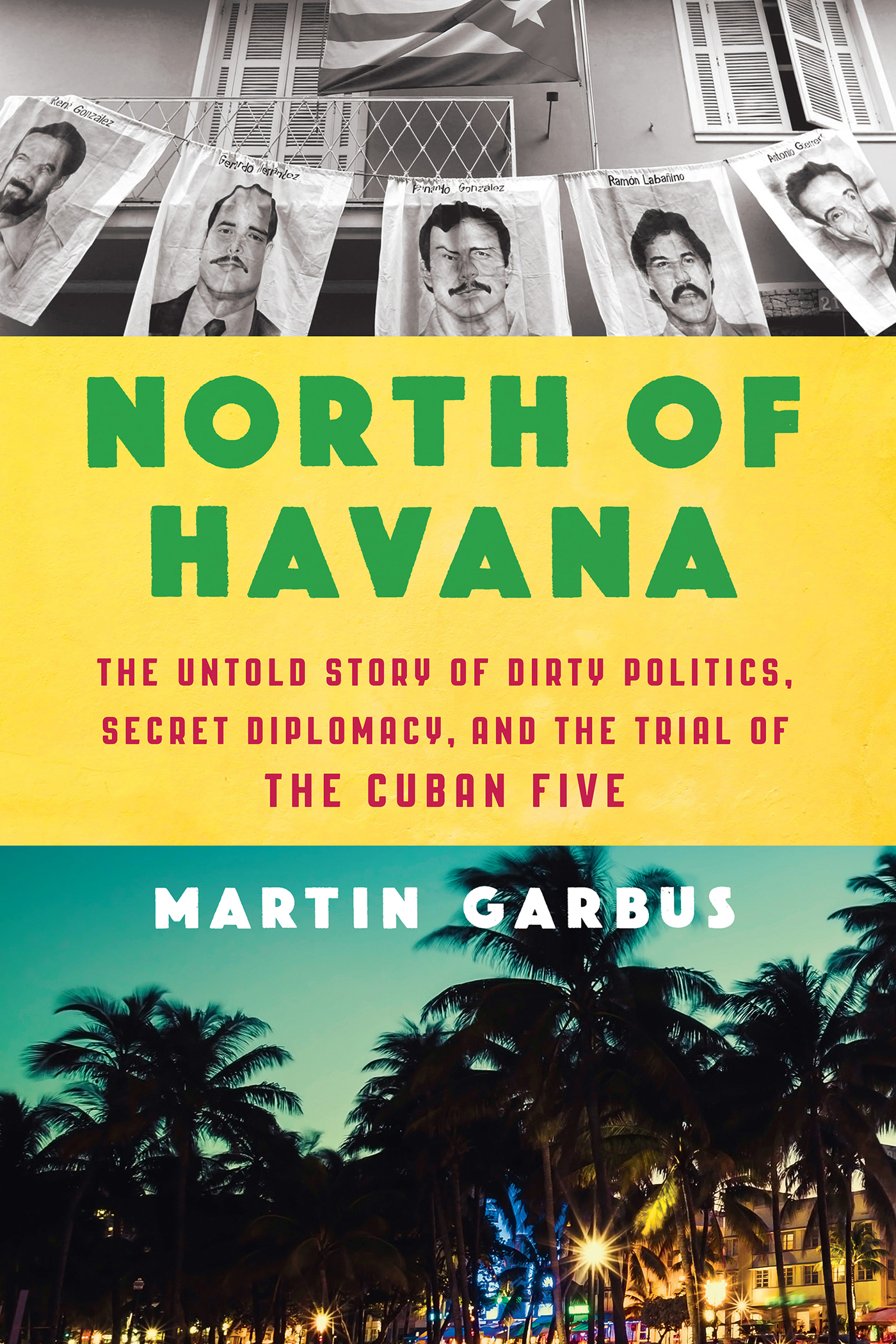

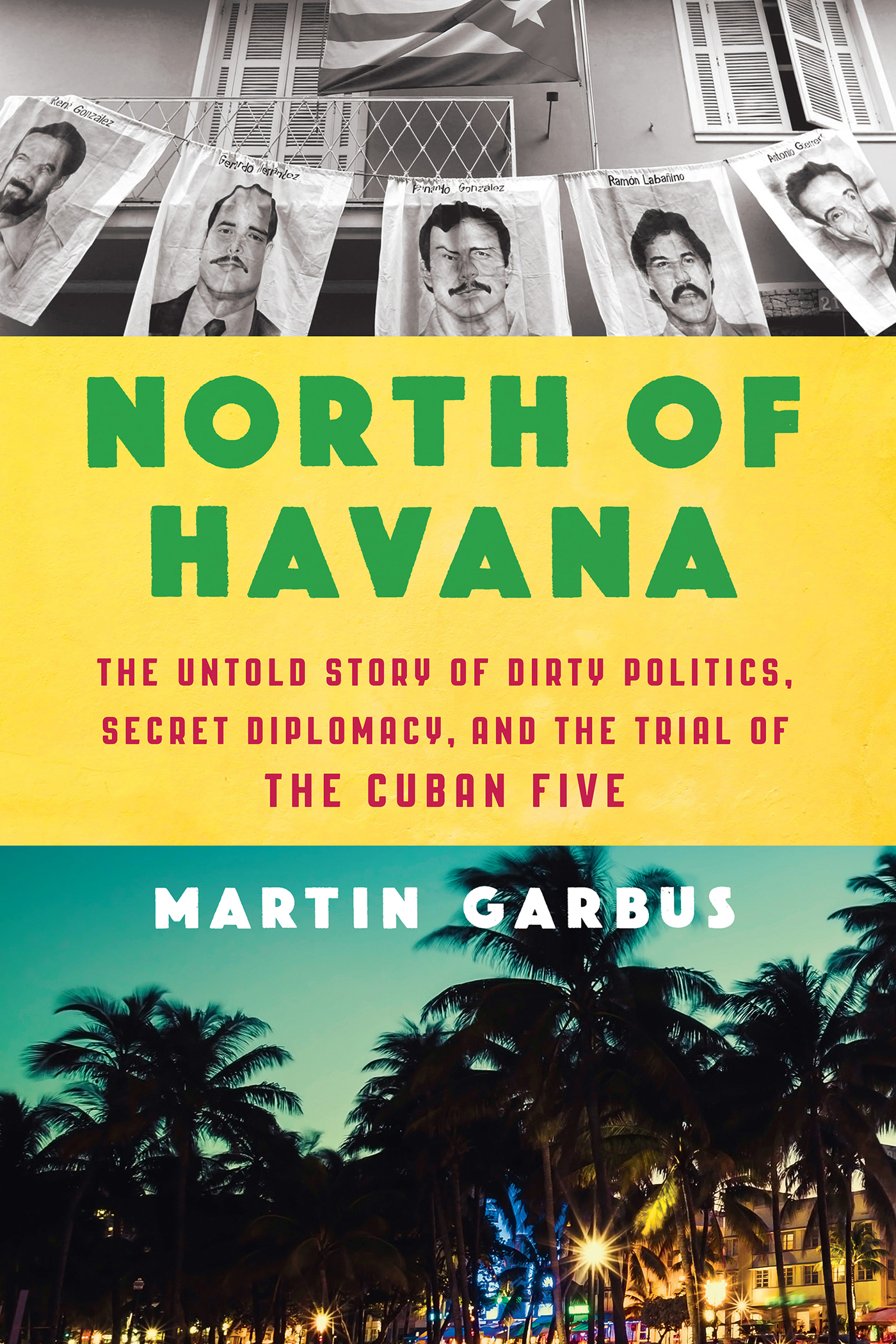

NORTH OF HAVANA

Also by Martin Garbus

The Next 25 Years: The New Supreme Court and What It Means for Americans

Courting Disaster: The Supreme Court and the Unmaking of American Law

Tough Talk: How I Fought for Writers, Comics, Bigots, and the American Way

Traitors and Heroes: A Lawyers Memoir

Ready for the Defense

NORTH OF

HAVANA

The Untold Story of Dirty

Politics, Secret Diplomacy, and

the Trial of the Cuban Five

MARTIN GARBUS

To Alessandra, Amelia, J.P., and Theo

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

F or several years in the early 1990s, Cuban exiles in Miami flew small planes over the Straits of Florida to assist Cubans who were fleeing their homeland in small boats, rafts, and inner tubes. These Samaritans called themselves Brothers to the Rescue, and they claimed to have effectively assisted 4,200 Cubans.

Right-wing Cuban exiles in Miami cried for justice. Politicians called for the indictment of Castro; some even called for the invasion of Cuba. The FBI and federal prosecutors in Miami found it through their pursuit of five members of a Cuban spy ring called the Wasp Network (La Red Avispa). None of them were based in Cuba. None flew a MiG. None planned the attack. But on September 12, 1998, Gerardo Hernndez, Antonio Guerrero, Ramn Labaino, Fernando Gonzlez, and Ren Gonzlezwho came to be known as the Cuban Fivewere arrested in Miami, and eventually tried and convicted for spying; one of them received two life sentences for his alleged connection with the shoot down.

Why were Hernndez and his team tried as if they had fired those missiles?

Here the story takes a surreal turn.

For decades, extremist Cuban exiles in Miami terrorized their homeland with bombings and madcap plots aimed at getting rid of Fidel Castro. In 1991, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of its subsidies to Cuba, the Cuban government was the most vulnerable it had been since the early days of the revolution. These right-wing exile groups accelerated their terrorist attacks. In early 1994, Castro responded by dispatching Gerardo Hernndez and the Wasp Network to Miami to infiltrate these extremist groups, monitor their activities, and, in the hope of stopping future attacks, report their findings to government agencies in Cuba, who, in turn, when they thought it was to their advantage, shared some of their intelligence with the United States.

The U.S. Attorneys Office in Miami spent three years investigating the shoot down of the Brothers to the Rescue planes; different federal prosecutors failed to turn up a single shred of evidence against Hernndez and his associates, and, one after the other, each declined to prosecute.

But by 1998, justice for the Brothers to the Rescue pilots had become la causa for Miamis right-wing exiles. Evidence didnt matter. The government charged Castros spies with espionage.

And then, nine months later, federal prosecutors charged Hernndezthe leader of the spy network and the only one of its members who had direct contact with the Cuban governmentwith the additional crime of conspiracy to commit murder. Their thinking was, if they squeezed Hernndez hard enough, they would get him to say something that would serve as the basis for an indictment of Fidel Castro, which is what powerful, well-financed anti-Castro exiles had demanded from the start.

The trial of the Cuban Five began in the fall of 2000 in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida, despite the fact that there was little possibility of Hernndezor any Cuban spyreceiving a fair trial in Miami. For months, the story of the shoot down dominated Cuban news broadcasts on Radio Mart and local TV. The Elin Gonzlez affair, which took place five months before the trial, further inflamed anti-Cuban sentiment.

Years later we would learn that the U.S. government paid Miami journalists and extremist Cuban exiles to write articles and commentary about the Cuban Five that expressed the anti-Castro exile communitys views. Government propaganda as sponsored journalism before and during a trial of Cuban agents? Unthinkable. But it happened.

During the trial, Hernndezs lawyers made repeated change of venue requests. All were denied. President Jimmy Carters former national security advisor Robert A. Pastor reviewed Hernndezs conviction and concluded, memorably, Holding a trial for five Cuban intelligence agents in Miami is about as fair as a trial for an Israeli intelligence agent in Tehran. Unthinkable that there was no change of venue. But it happened.

On June 9, 2001, the jury returned with the inevitable verdict: guilty.

Justice at Last! proclaimed the headline of the Miami Heralds story about the verdict. Months later, a federal judge sentenced Hernndez to two life sentences plus 15 yearsa punitive ruling that was blatantly out of proportion to sentences imposed in similar cases.

The guilty verdicts resonated around the world. Amnesty International and the United Nations slammed the judge.

Fidel Castros response was sustained outrage. He told a huge crowd in Havana, They will return. Volveran! Images of Gerardo Hernndez and the rest of the Cuban Five popped up on giant billboards throughout Cuba, with the caption: They will return. Volveran!

For years after the conviction of the Cuban Five, I discussed the case with Leonard Weinglass, a fine American lawyer and my dearest friend. Lenny got involved in the case immediately after the defendants were convicted, representing Antonio Guerrero, one of Gerardo Hernndezs co-defendants. Like Hernndez, he had been sentenced to life. In 2005 the 11th Circuit Court of Appealsa three-judge appellate court that was one of the most conservative federal courts in the countryreversed the 2001 conviction on the grounds that these defendants could not get a fair trial in the Miami federal court. The case, the court said, should have been tried in a different federal court. And it ordered an immediate retrial outside of Miami.

Although that retrial never happened, this first victory for the defense was an extraordinary triumph for the Cubansand for Lenny. I thought that, maybe, more could be done. And so, after Lennys death in 2011, I became Gerardo Hernndezs appellate lawyer.

Why did I? Well, lets go back. When I was 21, I enlisted in the army. I was court-martialed shortly thereafter. I had given a number of speeches to my fellow soldiers about recognizing Red China and protecting the Fifth Amendment rights of people called before officials like Senator Joseph McCarthy. The officer in charge of my unit said I should stop giving speeches like that. He meant it. My next speech was on the Sacco and Vanzetti case; he said I could be charged with treason. And it came to pass that a court-martial was convened in a small room on the bases first floor. But the army didnt charge me for my speeches. My supposed offense was going AWOL a number of times.

Was I guilty? Well, like nearly every other soldier at Fort Slocum, I often left the base to eat out or see friends or family and to sleep in New York City or Westchester County. Few of us ever signed out. It was the MO at the base and every enlisted man on the base knew itofficers did it themselves.

The morning my trial began, Master Sgt. Hatch, a distinguished World War II and Korean War veteran, came into the small courtroom. I had seen him at the basehis military bearing was consistent with his World War II career as a lieutenant commander in the navybut we had never met. Hatch asked the judges for permission to have me step outside the room while he spoke with them. They agreed. After 30 minutes they asked me to come back in.