The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2019 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-59355-5 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-59369-2 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-59372-2 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226593722.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Feeney, Megan, author.

Title: Hollywood in Havana : US cinema and revolutionary nationalism in Cuba before 1959 / Megan Feeney.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018020252 | ISBN 9780226593555 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226593692 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226593722 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion pictures, AmericanCubaHistory20th century. | Motion pictures, AmericanCubaInfluence. | National liberation movementsCuba.

Classification: LCC PN1993.5.C8 F44 2018 | DDC 791.4307291dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018020252

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

I have first to thank the many Cubans living on the island who made this project possible and deeply rewarding. Filmmaker Consuelo Elba lvarez made her home mine and became a second mother to me. Beyond feeding me and nursing me through a few bouts of heat exhaustion, she happily hoofed it through Havana with me, searching for old cines and office buildings. Her husband, Alejandro, who loves to ponder the universe from the eye of his telescope, was also brilliant at navigating me through the channels of Cuban bureaucracy back on earth. The men and women at the Instituto cubano de artes y industrias cinematogrficass Cinematecaincluding Vice Director Dolores Calvio and, especially, Mario Naitotreated me like a colleague and made my research possible.

I am also grateful to the many Cubans who kindly submitted to interviews. Walfredo Piera, a pre-1959 film critic, opened his home to me along with three bulging scrapbooks of publicity for Hollywood films that came to Havana during his youth, when he lovingly put the scrapbooks together. Subsequent interviews proved equally inspiring and fruitful, especially those with Jos Massip, Nelson Rodrguez, and Enrique Pineda Barnet, who each spent hours recalling for me their film-related activities in the 1940s and 1950s. I am also grateful to the reference librarians at Havanas Biblioteca Nacional Jos Mart and the Instituto de Literatura y Lingstica, who brought me edition after edition of crumbling Cuban fanzines and trade journals.

Back in the United States, I owe thanks to the University of Minnesotas Graduate School for a Harold Leonard Film Studies Fellowship and to the University of Minnesotas Humanities Institute for a second fellowship. This support allowed me to conduct research in Cuba as well as in the United States, particularly at the United Artists Collection at the Wisconsin Historical Society; in the Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami; at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Margaret Herrick Library; and in the Warner Brothers Archives at the University of Southern California. A grant from the Rockefeller Archive Center allowed me to dig into their files on the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs Motion Picture Division. I am grateful to the committed and knowledgeable archivists at all these collections, and especially to a few that went above and beyond: Barbara Hall and Kristine Krueger at the Margaret Herrick Library and Rosa Mara Ortz at the Cuban Heritage Collection.

Over many years, I have incurred intellectual and personal debts to many colleagues, including those who read and constructively commented on drafts in early stages: Matt Becker, Jennifer Beckham, Jenny Gowen, John Kinder, Dave Monteyne, and especially David Gray. Lary May, Elaine Tyler May, and Haidee Wasson have been invaluable advocates and uncompromising critics. I also owe thanks to Louis A. Prez Jr., who opened up his incomparable mental catalog of Cuba studies to advise me to research the Machado era as an important precursor to what would come in subsequent decades. At St. Olaf College, where I taught for years, I am thankful to members of the History Department who generously read a chapter draft. I am especially grateful to Jim Farrell, Eric Fure-Slocum, and Bill Sonnega. And, for helping me to imagine this project in new and exciting ways, I have to thank filmmaker Gaspar Gonzlez. More recently, I have come to owe a debt of gratitude to my editors at the University of Chicago PressDouglas Mitchell, Kyle Adam Wagner, and Jo Ann Kiserfor their faith in this book and their work polishing it into its present form.

I have been working on this book for more than a decade and could not have finished it without the support of my family, which has grown over that period. My fathers influence pervades every page; from him, I learned a passion for history and the cinema. The unswerving faith of my mother can be perceived particularly on the final page; she always knew I could get this done even when I did not. Such faith and encouragement might be expected of a mother, but I also received equal amounts from my sister, my in-laws, and my most constant friend, Dina Drits. And then there are my two wonderful children, whose mothers mind has been elsewhere in many moments throughout their young lives. I thank them for their love and patience. Finally, this book would not be possible without the loving support of my husband, John Geelan. For all this, and much more, I am grateful.

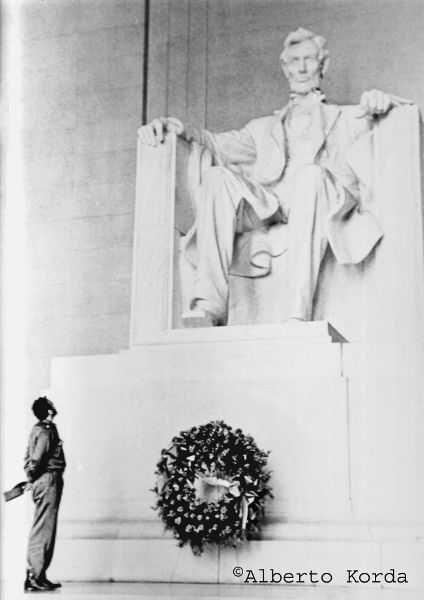

Fig. I.1. Korda (Alberto Daz Gutirrez), Fidel Castro at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC (also called David and Goliath), 1959. 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (Courtesy of Art Resource, Inc.)

Fig. I.2. James Stewart as Jefferson Smith gazes up reverentially at the Lincoln Memorial in a still from Frank Capras Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

Looking Up: Hollywood and Revolutionary Cuban Nationalism

Have you ever thought of the American motion picture in another lightas a powerful, even a revolutionary, instrument to increase human desires?... It keeps alive or recreates the desire for freedom where freedom and democracy have been snuffed out or flicker feebly. It keeps alive faith and hope in democracy.

ERIC JOHNSTON, President, Motion Picture Association of America, 1949

[Cubans] admire this nation, the greatest ever built by liberty, but they dislike the evil conditions that, like worms in the blood, have begun their work of destruction in this mighty republic. [Cubans] have made the heroes of this country their own heroes,... but they cannot honestly believe that excessive individualism, reverence for wealth, and the protracted exultation over a terrible victory [in the Mexican-American War] are preparing the United States to be the typical nation of liberty.... We love the country of Lincoln as much as we fear the country of Cutting.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).