EARL CAMPBELL

YARDS AFTER CONTACT

ASHER PRICE

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

Copyright 2019 by Asher Price

All rights reserved

First edition, 2019

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

utpress.utexas.edu/rp-form

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Price, Asher, author.

Title: Earl Campbell : yards after contact / Asher Price.

Description: First edition. | Austin : University of Texas Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018052872

ISBN 978-1-4773-1649-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4773-1907-9 (library ebook)

ISBN 978-1-4773-1908-6 (non-library ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Campbell, Earl. | Football playersUnited StatesBiography. | African American football playersBiography.

Classification: LCC GV939.C36 P75 2019 | DDC 796.332092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018052872

doi:10.7560/316498

For my parents and my brothers

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Even beneath the supernova-bright lights of the Astrodome, Earl Campbells eyelids are slipping. Its late in the fourth quarter of a midseason seesaw game on Monday night, and his Oilers are huddling up on the sandpaper-rough artificial turf, stretched thin over a hard concrete subfloor, far below the arenas vast roof. The crowd of more than fifty thousand is a frothy sea of shaking powder-blue-and-white pom-poms, and on the sidelines, the big-haired Derrick Dolls strut in their shiny white boots. Facing Don Shulas storied Miami Dolphins, Earl has already carried the ball nearly thirty times, including on nine of his teams previous thirteen plays. He has gone for three touchdowns, scoring them with power and speed: on one three-yard run, he lowered his shoulder and lifted a defensive end up into the air as if he were a bull flinging a matador; in another, he rammed into a linebacker with his head, leaving his opponent sprawled out on the Astroturf. Crunching power, Howard Cosell, in his staccato Brooklynese, tells the nearly fifty million Americans watching the game on ABC. Each time Campbell scores, the giant Astrodome scoreboard lights up with a rendering of a bull snorting steam out its nostrils. Earl Campbell had some head-on collisions with our players, Shula would say after the game. I think he won them all.

But all that impact has left Earl Campbell wobbly.

Big fellow, you got one more in you? Dan Pastorini, Houstons shaggy-haired, perennially beat-up playboy quarterback, asks him in the huddle.

With just over a minute left, the Oilers have the ball and a five-point lead. At second-and-eight from their own nineteen-yard line, all they need to ice the game is a first down. Coach Bum Phillips, the lovable cowboy-quipster riding herd on this resurgent Oilers team, has signaled that he wants to go with Campbell, the reliable rookie, once again.

The play is Toss 38. Pastorini will lateral to a sweeping Campbell, who is to turn upfield behind a leading fullback or pulling guard. Its a routine sequence, one that is deemed a success if it nets four or five yards. Except Tim Wilson, the Oilers fullback and lead blocker, glances at Earl as the huddle breaks. I swear, his eyes were closed, Wilson said later. He looked like he was about to drop. I had to tell him the play, and he barely responded. Campbell has a foggy look from a night of pounding. Its on two, Wilson tells him, reminding him of the snap count. Follow me. Were going right.

Act like youve been there before goes the old sports chestnut, and Earl Campbell had: only five years earlier, on this very field, announcing himself as the best schoolboy football player in the nation, he had lifted his newly integrated high school football team to the state title. Two years after that, he was back in the same building, leading the University of Texas Longhorns to victory in the Astro-Bluebonnet Bowl.

Happy hoots and whistles rain down from the frenzied crowd, and on the terraced seating levels the dome feels as if its vibrating, a space-age building about to launch itself skyward. A sign hanging from one of the decks says, Look Out America, Here Comes Houston. For years, this citys losing squads had played before half-empty arenas, but now, with Campbell on board, the team is 74. The marquee Monday Night Football matchup feels like a coming-out party. Theyve waited a long time for professional football excellence in Houston, and theyve got it now, Cosell nasals out. An underpublicized team, an underappreciated team.

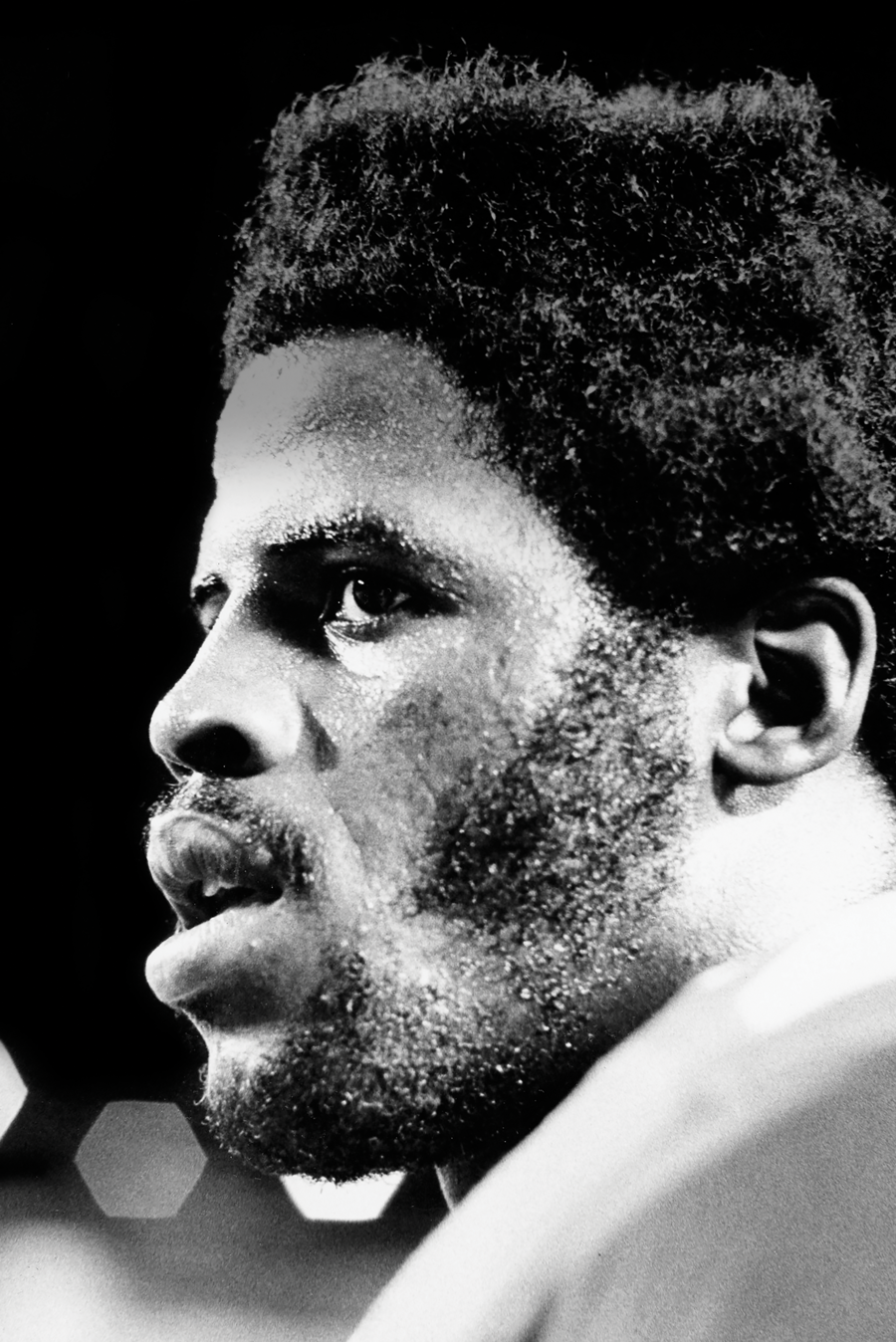

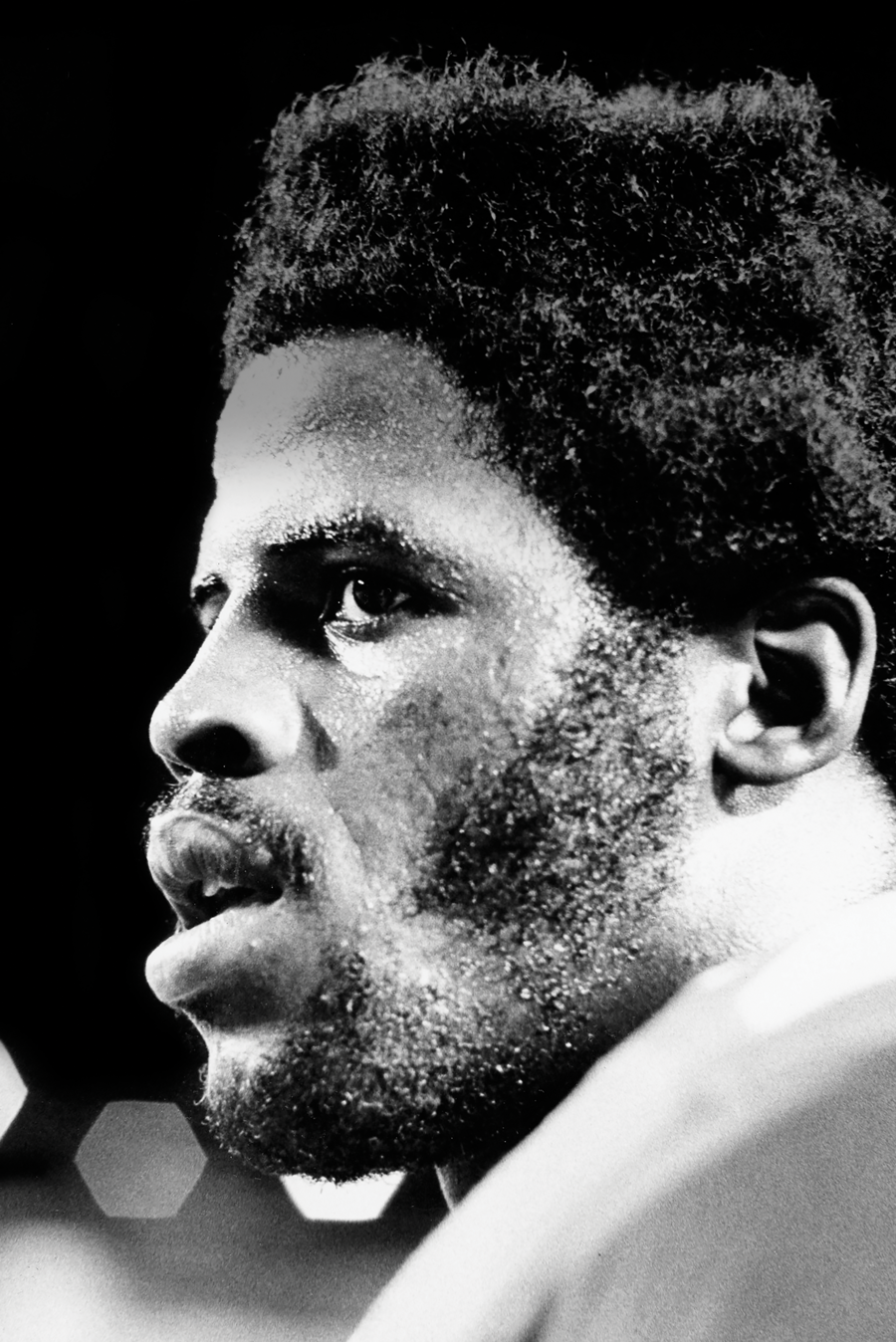

Wilson, squeezing into his stance a couple of yards into the backfield, reaches a hand behind him, lays it against the small of his own back, and flashes an upside-down victory signgiven the timing needed in this football waltz, he wants to make sure Campbell remembers that theyll start on the second hut. Behind him, dropped into a frozen stance of his own, is Campbell, all of twenty-three years old, his face and full beard bursting with sweat, his massive thighseach thirty-three inches in circumference, the size of a grown mans waistnearly vibrating in anticipation. We make four sizes of thigh pads, a Houston equipment manufacturer once observed, small, medium, large, and Earl Campbell.

Pastorini receives the snap, turns over his right shoulder and pitches the ball. Campbells eyes suddenly widenWhen that ball got in my hands, that leather, its like I turned into a different human being, he once said. Wilson lands a glancing block in the backfield, just enough to protect Campbell from a loss of five yards. But now five Dolphins, including two speedy cornerbacks, have an angle on the running back. If they can force him out of bounds, they can stop the clockand maybe give their own offense the ball with one more shot in a high-scoring game.

But Earl Campbell doesnt do out of bounds. He possesses what the writer Willie Morris once described as the quality of potentialitythat feeling that at any moment he might go the distance. And so, just as the Dolphin defenders appear to close in on their quarry, Campbell, as if he has rockets laced to his cleats, suddenly outstrips them all. Alfred Jackson, a wide receiver who played with Campbell at the University of Texas, once said he could sense when Earl was striking a big play even as he looked to lay a block downfield: You could always tell when Earl got in the open because the crowd would roar. Just such a rumble rises out of the Houston crowd now as Campbell sprints down the right sideline past the Derrick Dolls, past the blue-and-white pom-poms, across the Astroturf, all of eighty-one yards for the touchdown.

He gets to the end zone so fast that it seems like a good minute before his jubilant teammates join him to celebratemostly Campbell just stands there, hands on hips, sucking air. After half collecting himself, he staggers to the sideline, where Bum Phillips greets him with a big-lipped kiss on his sweat-beaded cheek.

What youve seen tonight, ladies and gentlemen, Cosell says, in his grandiose way, is a truly great football player in the late moments take total personal command of a game.

Back in the locker room, Campbell told reporters that even after he got past the first line of defenders he didnt think he had the wind to make it all the way down the field. Then I saw pure sideline, and I decided to keep running until somebody knocked me down, he said. He had never been so happy to get in the end zone and get something out of my hand, that football. He was so exhausted, he said, that even getting back to the Houston sideline had seemed an impossible chore. It looked a mile away, he half joked.

Next page