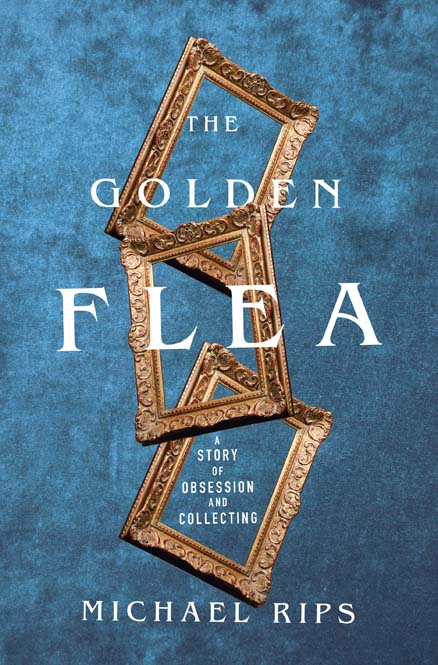

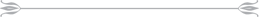

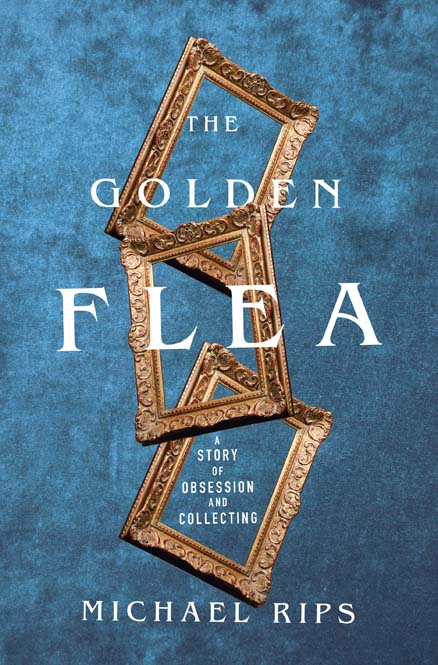

THE

GOLDEN

FLEA

A Story of Obsession

and Collecting

MICHAEL RIPS

W.W NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publisher Since 1923

ALSO BY MICHAEL RIPS

Pasquales Nose

The Face of a Naked Lady

A BLACK MAN IN A WHITE HAT STOOD SLEEPING against a brick wall. Next to him a long ramp. On the other side of the ramp, a white man in a black hat. Snow gathered at their feet.

At the bottom of the ramp was a parking garage.

There were people in that subterranean space.

They talked, smoked, and set up tables. Steam from their coffee rose into the air from the street. It was four-thirty in the morning.

The black man, now awake, pulled the brim of his hat down to cover the hole where his eye had been.

Unlocking the chain that extended across the entry to the ramp, he led me into his cave.

From there, I have yet to return.

....

INSIDE THE CAVE, the man walked me to his table. Retrieving a lawn chair, he lay down and slept.

Among the objects on his table were slices of carpet, abandoned suits from the laundry down the street, appendages of dolls from the 1950s, a pair of tan shoes with broguing, a womans golf bag, a stack of drawings from a high school art class.

None of these had prices, and all were assembled into a single mound.

When the man awoke, I asked whether he would retrieve an itemthe shoes.

What will happen if I do that? he asked.

Everything collapses?

Would you like that?

I suppose not.

Then why trouble me?

The man had crooked teeth but plush, purple gums that sparkled when he spoke.

At the next booth sat a small man with sentimental eyes. Against his table were a pair of metal crutches. Five empty frames hung behind him on the wall of the garage.

This, I said, pointing to one of the frames. Do you know where it is from?

It was hand-carved and leafed in silver.

No.

Or this one? I pointed to another.

No.

Any of them?

No.

I took down a frame.

Do you like it? he asked.

I paused.

He smiled.

A frame or painting or antique table encountered anywhere else, a gallery, museum, or home, comes with an explanatory context: it may be near similar frames, paintings, and furniture with which it shares a style or provenance; it may be accompanied by a text; the owner may have a reputation for collecting things that are important or interesting or, at any rate, are not forgeries.

But here the objects were naked, and effulgently so.

....

THE GARAGE HAD two floors. On each, twenty-five to thirty booths ran along the brick walls, and twenty booths were set up in the center. In all, there were one hundred vendors, offering paintings, lithographs and photographs, ceramic vases, silver trays, models of ancient ships from museum gift shops, boxes of cuff links, kimonos, used napkins and tablecloths, dinnerware, picture frames, pliers, gold and silver brooches and necklaces, antique rugs, lamps, chandeliers, and furniture from all periods, mug shots, canes, vintage clothes, costume jewelry, Asian scrolls, screens, and jade, sports memorabilia, and African art. And throughout there were stacks of crumbling newspapers and magazines.

On top of one of the stacks, on my first day there, was a newspaper from the 1950s, announcing that outside a small town in Iowa, not far from where I had grown up, a child had been devoured by a combine. There was a picture of the combine, the driver of the combine, slumped to the ground, and an ambulance. A man from the ambulance had his head turned, looking for the child. But, as the driver knew, no child remained.

Oil and gasoline pooled on the floors from the cars parked and serviced in the parking garage during the week. When it rained greatly, shards of paint and filth fell onto the booths and sewage backed up through the drains. Fluorescent lights and asbestos hung loosely from the ceiling, and nails protruded from the walls, hammered there by vendors to display their paintings. With no heat, vendors warmed themselves with coffee and layers of coats. Nonetheless, the concrete walls seemed capable of withstanding any assault, and the pipes that lined the walls did well as supports for vintage clothes, tablecloths, stall signs, and anything else that couldnt fit on the crowded floors.

Beyond the garage was a constellation of open-air parking lots, which were also rented out to vendors on the weekends. There were three large lots on Sixth Avenue between Twenty-Third and Twenty-Seventh Streets. Down Sixth Avenue, between Sixteenth and Seventeenth Streets, was another lot; this was the smallest of the lots and was, typically, the last that a buyer would visit. On Twenty-Fifth Street between Sixth and Broadway, next to a large church (once Episcopalian, now Serbian), was another parking lot used as a flea market on the weekends. Edith Wharton (then Edith Jones) was married in the church.

Visitors to certain lots on Sixth Avenue were required to pay a fee to get in, usually a dollar. The lot next to the church required the same. If, however, you wanted to get in before nine oclock, the fee was $5. Early access meant that the buyer would get a first look at what was being sold by the vendors. Some of the lots opened as early as five or six in the morning. Vendors who arrived at that time traded goods with each other.

Across the street from the parking lot on Twenty-Fifth Street was a building that housed dozens of antiques dealers, each with their separate stalls and metal security grates. Some were open during the week, others were not. Those vendors who were not open would leave a note with their phone number on the outside of the stall. All vendors, though, were open on the weekends, owing to the crowds drawn to the neighborhood by the flea market. A similar building was just east of the garage on Twenty-Fifth Street.

Both buildings, along with those that surrounded them, had once housed businesses connected to the Garment District, which ran from the mid-Twenties up to Forty-Second Street and from Fifth to Ninth Avenues. At one time, over 90 percent of the clothing sold in America was manufactured in the Garment District. That had dropped to 3 percent.

In the 1970s and 80s, as the garment industry evaporated, a cataract of underground clubs, prostitutes, artists, transvestites, writers, and junkies flowed into the neighborhood. At the same time, with the price of real estate rising in the West Village, gays and lesbians moved into Chelsea, which was nearby and more affordable. Gay bars and sex shops filled Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith took up residence in the Chelsea Hotel in 1969, and Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols killed his girlfriend there in 1978. The flea was a meeting place for the various groups filling Chelsea: rare yet inexpensive items could be found to fill their apartments, artists took inspiration from the accidental combinations of objects, and those who were leaving the clubs and bars in the early morning had a place to go before returning home. People dressed in outlandish costume just to attend the flea market. It was a place to display and create oneself, a diorama of drag and exoticism.

Next page