Table of Contents

For my parents, Clarissa Starr

and Patrick Stanton

A NOTE TO THE READER

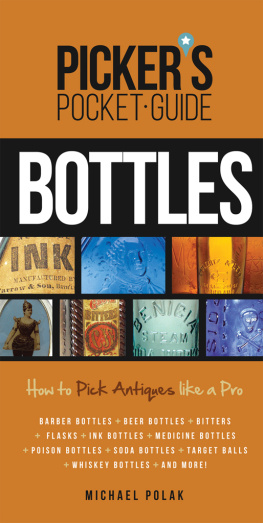

My journey into the flea market and antiques subculture began in 2000, when Curt Avery, whom I met in college in the 1980s, flew from Massachusetts for an auction in Ohio, where I was in graduate school. I was immediately intrigued by the storythat with $4,000 in his pocket he traveled a thousand miles after a couple of old bottles, that he stared at a single bottle for a half hour during the preview, turning it this way and that, holding it up to the light, running his fingers over its lip. How he hid behind a pole at the rear of the room to bid, using me as a decoy to fool his competitor. Four years passed, and I had a chance to work a flea market with him. Over the course of the next six years, when I could get away from my job, I entered this strange flea realm as a participant observer. Curt Avery gave me access into this world, tutored me, and spoke to me for hours and hours about the antiques business, partly as a favor, but mostly I believe because he wants people to understand and appreciate antiques.

From the beginning, Curt Avery asked to remain anonymous, which allowed him to speak candidly, and to remain the private, modest person he is (Why should there be a book about me?). In our Facebooked, YouTubed, celebrity-idolizing culture, its rare that someone does not want attention. To honor my agreement with him, and to protect his privacy and the privacy of others, I have changed his name and the names of some dealers, collectors, and customers, and I have made slight moderations to other identifying characteristics. I used real names for public figures, Antiques Roadshow personnel, celebrity collectors, museum curators, top dealers, auctioneers (except Walt Johnson), show promoters, store and/or Web site owners, and others whose names have previously been made public in articles. This is a work of nonfiction; there are no composite characters, no fabricated scenes or dialogue. Most of the material I observed myself, though a few stories were related to me. As a work of synthesis, this book owes a great debt to dozens of historians, journalists, cultural critics, anthropologists, collectors, and scholars, on whom I relied for documentary research. I am not an antiques dealer, collector, or historian; I sought only to convey a subculture that fascinates me. Any misrepresentations or mistakes about the field of antiques and collecting are fully my own.

PROLOGUE

Treasure Hunters: The Reality

Curt Avery has an idea for a reality show: Give ten antiques dealers a thousand bucks each and turn them loose on the carnival fields of Brimfield, the countrys largest outdoor flea market and antiques show. You continually buy up, trading for more money, more valuable objects, he says. You take a piece of shit and you turn it into a Chippendale chair.

For Avery, this is not a reality show, but reality. The stakes are higher than a brief moment of fame. Avery must do this every day to put food on the table, pay bills, for his sons braces, his daughters dance lessons, for the college fund, his own retirement. Every week he plays to win, searching through piles of junk at flea markets or through fancy antiques stores, avoiding the glut of reproductions, the clever fakes (land mines, he calls them), outmaneuvering his competitors at auctions, applying twenty years of hard-won knowledge, wisdom that he gained the long wayawake at dawn for flea markets, up till midnight hitting the booksand the expensive way, the most painful lessons of all: buying mistakes. Another antiques dealer I met, Wesley Swanson, learned about antiques by losing thousands of dollars, he says, just not all at once.

Its not an easy life. There are no paid sick days or vacation time, no pension fund or retirement plan, no corporate ladder where hard work gets you recognized, no year-end bonus or profit sharing. No safety net. In this endeavor, you survive by your wits alone. Or not. In his early days when the learning curve was ahead of him and profits meager, Curts wife, Linda, out of work with their second child, would beseech him to sell a bottle from his collection, trade a nineteenth-century bitters bottle, perhaps, for a plastic one filled with juice. How many guys my age are in this business? Avery says. Its like giving up on normal life and running away with the circus.

But how many people have a job where every day is a hunt for treasure, every day infused with the hope and possibility of finding a pot of gold, something to love and keep, something unique. Gold is where you find it, Avery says, meaning that a great antique can show up anywherejunk stores, yard sales, flea markets, auctions, high-end antique shows. The beauty of this business, he says, is that you can do it anywhere. You just need a checkbook, a pen, and a pair of eyes. True, but the checkbook needs a healthy balance, and the eyes must be knowing. Its all about recognition, he says. He tells me about a period card table that sat in a Gloucester, Massachusetts, consignment shop for months and months priced at $600, until one day a savvy antiques dealer recognized the tables value, bought it, and sold it at auction for some $14,000. Each day in the life of an antiques dealer challenges his or her knowledge and instincts, an aesthetic IQ test. Recognizing the prize is no easy feat. A seven-by-ten-foot painting hung in an elementary school auditorium in North Attleboro, Massachusetts, for forty-eight yearsits value unknownuntil one day a man recognized the painting as Afghans, an important work by Alexandre Iacovleff. The painting was appraised at over $800,000.

Even with knowledge, it takes a workaholic compulsion to unearth treasuresrising before dawn for flea markets, knocking on doors, taking one last tour around the antiques shows after everyone else has left, outfoxing other dealers, doing time in the attics and basements of homeowners looking to divest. Like a rock star on tour, Avery is on the road peddling his wares nearly every weekend: New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut, a grueling circuit of thirty to forty shows each year.

There are dealers who take the easy way out by selling reproductions, or passing off fakes and forgeries to unwitting collectors, crossing over to the dark side, Avery saysthe greatest peril to the pleasure and business of antiques. Like gold prospectors in the Wild West, the antiques and flea market world can attract colorful characters, sometimes unsavory or unscrupulous, sometimes canny and diligent. The competition is fierce, the rules few, and the true treasures are rare or well hidden except to the sharp eye of the autodidact.

Like all dealers, Curt Avery awaits the perfect storm of antiques, the day when all the factors converge in a cosmic alignmenta bit of arcane knowledge from two decades of self-study that signals this object is the one, the opportunity created through hard work, being out early and up late, and the most elusive factor, luck, the antiques gods smiling on him, his competition asleep or absent, and hes got a pocket full of casha brilliant shimmering instant on a dusty flea-market field or in a posh antiques shop, when there before him that object sits on a table or shelfthe lottery ticket, the retirement piece, the super-best, the Holy Grailand he knows it.