Daniel Coleman - Yardwork

Here you can read online Daniel Coleman - Yardwork full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Wolsak and Wynn Publishers Ltd, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Yardwork

- Author:

- Publisher:Wolsak and Wynn Publishers Ltd

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Yardwork: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Yardwork" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Yardwork — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Yardwork" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

How can you truly belong to a place? What does being at home mean in a society that has always celebrated the search for greener pastures? And can a newcomer ever acquire the deep understanding of the land that comes from being part of a culture that has lived there for centuries?

When Daniel Coleman came to Hamilton to take a position at McMaster University, he began to ask himself these kinds of questions, and Yardwork: A Biography of an Urban Place is his answer. In this exploration of his garden which Coleman deftly situates in the complicated history of Cootes Paradise, off of Hamilton Harbour the author pays close attention to his small plot of land sheltered by the Niagara Escarpment. Coleman chronicles enchanting omnivorous deer, the secret life of water and the ongoing tension between human needs and the environment. These, along with his careful attention to the perspectives and history of the Six Nations, create a beguiling portrait of a beloved space.

Beyond Understanding Canada: Transnational Perspectives on Canadian Literature (co-editor)

Countering Displacements: The Creativity and Resilience of Indigenous and Refugee-ed People (co-editor)

In Bed with the Word: Reading, Spirituality, and Cultural Politics

Masculine Migrations: Reading the Postcolonial Male in New Canadian Narratives

ReCalling Early Canada: Reading the Political in Literary and Cultural Production (co-editor)

Retooling the Humanities: The Culture of Research in Canadian Universities (co-editor)

The Scent of Eucalyptus: A Missionary Childhood in Ethiopia

White Civility: The Literary Project of English Canada

I LOVE IT WHEN , after the dark of summer sleep, I step out on the back stairs from the sunroom with a cup of coffee in hand and take my first breath of morning air. The early light threads the green leaves of the maple in our neighbours yard to the east. It filters downward, lighting dewdrops that hang from blades of grass. My eyes narrow when I stretch and yawn, making the prism of dew on a single blade flash emerald, then lime, before winking magenta, sapphire.

The magic of morning in the backyard.

The fire in the dewdrop echoes the flame that leaps when a breeze shivers the scarlet and wine-red leaves of the Bloodgood Japanese maple in the northwest corner of our yard. It is Mosess bush that burns and is never consumed.

I no sooner think, Take off your shoes this is holy ground, than a truck, backing into the university maintenance building below our place, flings its backup alarm into the morning air: Beep. Beep. Beep. Okay, maybe not so holy.

The strident noise is cut by a bright, piercing whistle, so sharp and clear it rinses the air of all other sound. Its hard not to smile at the song of a Carolina wren. Its tiny body seems an utterly impossible source for such a huge voice, like a rusted clothesline pulley turned in four or five brisk triplets. Its blazing cycles stop abruptly, leaving the world echoing and ready.

Good morning! I answer, trying not to shout, not to draw attention from the maintenance guys below. Good morning.

How many hours have I spent out here, just like this, tasting the busy silence of an early morning? How many evenings have Wendy and I spent drinking in the sparks of fireflies that hover over the lawn in July? How many afternoons bending our backs to wheelbarrows and rakes, laying flagstone or digging compost? Like every yard in the world, ours is a small plot of earth whose unique personality emerges from both the combination of whats given the lay of the land, the quality of the soil, the length of the growing year and yardwork the amount of care and attention devoted to it.

Im down to the last sip in my cup. But my heart runneth over.

I am not accustomed to belonging. I am foreign to the idea of staying put. I was born and raised in a spiritual diaspora, and the place in which my family lived was never home. In The Scent of Eucalyptus: A Missionary Childhood in Ethiopia , Ive described how my parents were Canadian Protestant missionaries who met and married and raised four children in that East African country. The missionary society of which they were part had members around the globe, working originally in West Africa, then spreading across the continent into Europe, South America and eventually Asia. Like the other members of this far-flung community, my parents lived peripatetic lives, assigned by mission administration at different times to different ministries in different places around the country. My mom was born on a farm, so she knew all about yardwork planting gardens of beans, radishes and beets, as well as zinnias for beauty. But none of the houses we lived in were our own, nor did we expect to stay in them long. The places we lived in, with their unique qualities from cedarwood floors to painted clay-and-wattle walls were steps on an eternal pathway, since the kingdom of God was not of this earth and our sights were set on eventually reaching the heavenly Promised Land.

When I completed high school, I followed my older siblings to Canada, the land of our citizenship, which our parents called home, and which we had visited but where we had never lived permanently. I entered university, met and married my wife, Wendy, and eventually graduated from the University of Alberta with a doctoral degree in Canadian Literature. Jobs for literature professors are few and far between, however, so when I was offered a position in my field at McMaster University in Hamilton, we both felt I must accept it. Neither of us wanted to move here. For one thing, our families (the parts that lived on this continent) lived in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and we wished to remain near them. And like most Canadians, we had only seen the glowering smokestacks of Hamiltons steel mills from the QEWs six-lane Skyway Bridge on our way from Toronto to Niagara Falls, and we thought the city looked like an environmental disaster. But there were no other jobs in sight, so we reluctantly moved to this soot-stained, gritty city that grips the southwestern shoreline of Lake Ontario.

Who knows where fondness for a place grows from? Perhaps it is a reaction to placelessness, the un-belonging of my childhood. Perhaps it is part of my increasing perception that in an age of climate change places have to matter. Perhaps my growing attachment comes from identifying with this damaged place as an environmental underdog. Certainly, a major turning point in my thinking about this place came from my encounter here in Hamilton with Indigenous thinkers and their understanding that all creation around us is alive and actively trying to teach us. Vanessa Watts, a friend and colleague who is Hodinhs:ni and Anishinaabe, calls this understanding place-thought: the awareness that places are alive, have spirit and are providing us with everything we need to live. I began to wonder if I myself could begin to learn some place-thinking; if I could transfer the skills I had developed in my bookish education toward reading the relationships that constitute a place, a landscape.

But even as I thought about how to get started, I knew immediately that landscape is too big, dense and complex. Anyone who begins to pay attention, real attention, to even one square metre of any place on earth, from the microscopic beings that turn leaf matter into soil to where water goes after soaking into that ground, will soon be overwhelmed. In order for a beginner like me to notice anything at all, I needed to limit my scope. So I decided to focus on my own backyard. I knew that even this small place would be too complex, but at least it would be convenient right outside my door. I could watch it every day, through each season.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

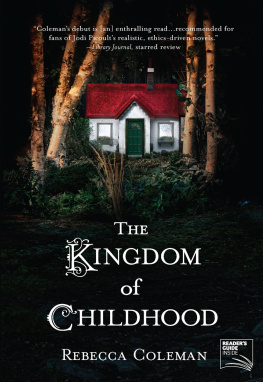

Similar books «Yardwork»

Look at similar books to Yardwork. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Yardwork and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.