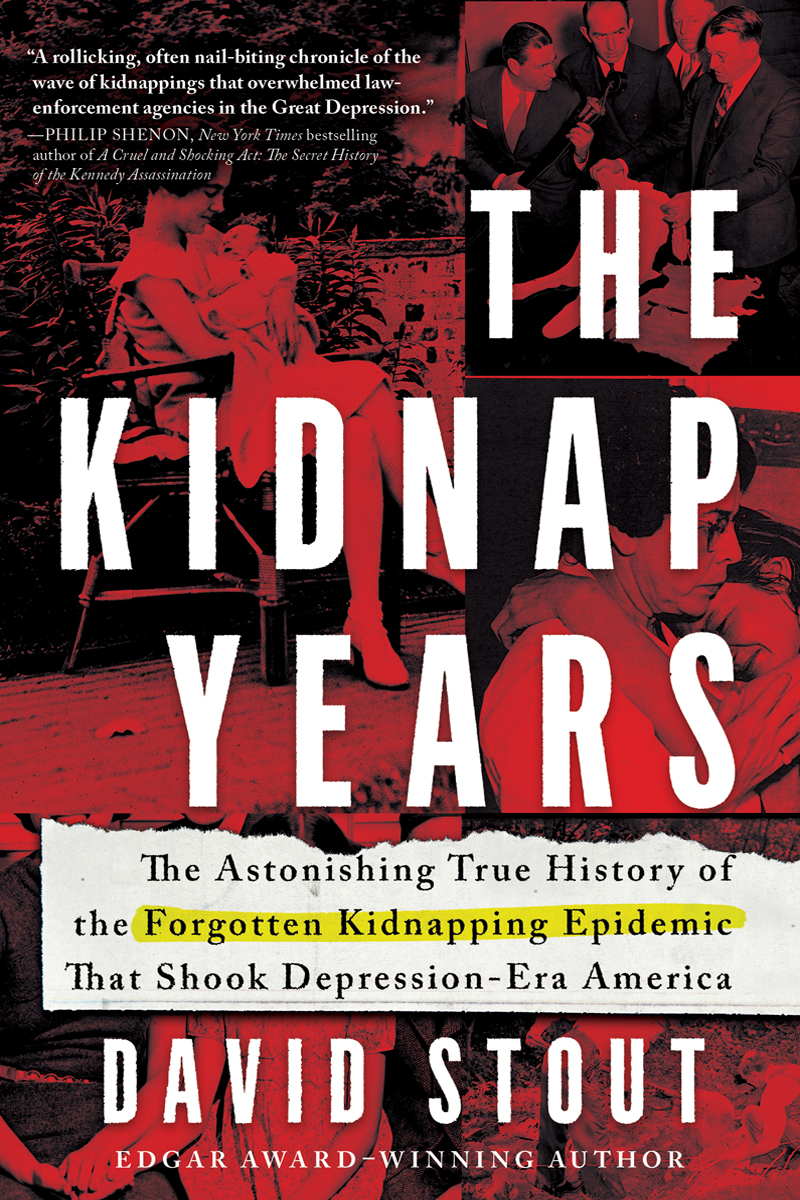

ALSO BY DAVID STOUT

Carolina Skeletons

Night of the Ice Storm

The Dog Hermit

Night of the Devil

The Boy in the Box

Copyright 2020 by David Stout

Cover and internal design 2020 by Sourcebooks

Cover design by Sarah Brody

Cover images New York Times Co./Getty Images, Bettmann/Getty Images, STILLFX/Getty Images

Internal design by Ashley Holstrom

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought.From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stout, David, author.

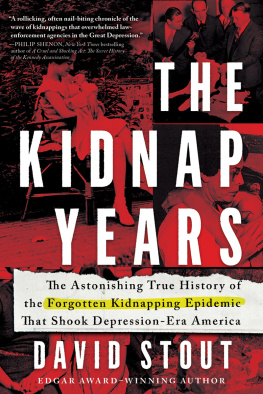

Title: The kidnap years : the astonishing true history of the forgotten kidnapping epidemic that shook Depression-era America / David Stout.

Description: Naperville, Illinois : Sourcebooks, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019032997 | (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: KidnappingUnited StatesHistory20th century. | CrimeUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HV6598 .S76 2020 | DDC 364.15/4097309043dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032997

For Rita, my rock and my light

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

One winter day a long time ago, a handsome woman in her early forties was found dead in a snowbank off a highway in northwestern Pennsylvania. She had been strangled. The homicide was big news around Erie, Pennsylvania, where I grew up. The killer, it was soon revealed, was a man the victim had begun dating after her marriage turned to ashes. For weeks, the crime was grist for newspaper headlines and chatter in barbershops and saloons. It was even featured in the true-crime pulp magazines of the era.

The victim was my mothers sister.

I recall the coffin being wheeled out of a candle-scented church as a choir sang farewell and my aunts relatives stood grim-faced, some with tears on their cheeks. I was in college at the time, old enough to understand that I had been granted wisdom not bestowed on everyone. I understood that a murder spreads an indelible stain, dividing the lives of people close to it into Before and After.

So began my interest in crime. It is an interest that has only deepened with the passage of years. It has compelled me to read scholarly tomes as well as lurid accounts of sensational cases. It has drawn me to courtrooms and prisons and to the death house in Texas, where I witnessed the execution of a pathetic, dirt-poor man who had raped and killed his ex-wife and her niece in a drunken rage.

My preoccupation with crime was known to my editors during my newspaper career. Thus, on January 12, 1974, an arctic cold Saturday in Buffalo, my bosses at the Buffalo Evening News sent me to the Federal Building for a somber announcement by the resident FBI agent. The fourteen-year-old son of a wealthy doctor in Jamestown, New York, sixty miles southwest of Buffalo, had been kidnapped the previous Tuesday. Three teenagers had been arrested Friday, and most of the ransom money had been recovered in the home of one of them.

But the boy was still missing.

The FBI agent told reporters that the bureau had entered the case because the victim had been missing for more than twenty-four hours. Ergo, there was a presumption under the Lindbergh Law that he might have been taken across state lines, so the feds were authorized to assist the local cops.

I knew about the 1932 kidnapping and murder of the infant son of legendary aviator Charles A. Lindbergh. So I assumed that horrible crime inspired the law.

Not exactly.

I was surprised to learn that, despite acquiring its informal name from the Lindbergh crime, the Federal Kidnapping Act of 1932 was a reaction to a string of abductions that began before the Lindbergh baby was even born and continued while he was still squirming happily in his crib.

There were so many kidnappings in Depression-era America that newspapers listed the less sensational cases in small type, the way real estate transactions or baseball trades were rendered. There were so many kidnappings that some public officials wondered aloud if they were witnessing an epidemic.

In fact, they were.

From New Jersey to California, in big cities and hamlets, men and women sat by a telephone (if the household had one) or waited for a postmans knock, praying that whoever had stolen a loved one would give instructions for the victims deliverance. There was usually a demand for money, sometimes for a fantastic sum, other times for a small amount that might even be negotiated down. It was possible to put a dollar sign on the value of a life.

A familys ordeal might last for hours and end happily. Or it might go on for days, with the relatives knowing that as time passed, hope ebbed. For some people, the ring of the phone or the knock on the door brought heartbreak and bottomless sorrowthe very emotions visited upon the family in Jamestown, New York, in 1974.

There was never much mystery behind the Jamestown case. The instructions for delivering the ransom were simple and unimaginative, giving investigators plenty of time to stake out the drop site and photograph whoever picked up the money. The ransom demand was a mere $15,000, a fraction of what the doctors family could have paid.

The amateurish nature of the scheme had caused investigators to suspect early on that the crime was the work of local teenage dim bulbs. Sure enough, teachers at the area high school easily identified the youth who had been photographed picking up the money. He was a supervisor at a teen center where the doctors son had said he was going just before he vanished. The voice on a tape-recorded call to the doctors home was recognized as that of a nineteen-year-old high school dropout who hung out at the teen center.

When two eighteen-year-olds were arrested, they admitted theyd done something wrong under the guidance of the nineteen-year-old, but they swore they hadnt signed on for anything that might bring harm to the boy.

Ominously, the nineteen-year-old, in whose home the ransom money was found, kept quiet about the boys whereabouts. Searchers combed the snowy woods around Jamestown on Saturday and Sunday until the boys body was found lashed to a tree. He had been beaten to death, probably with a metal pipe or a hammer judging by the wounds to his head.