Paolo Tullio - North of Naples, South of Rome

Here you can read online Paolo Tullio - North of Naples, South of Rome full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: The Lilliput Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:North of Naples, South of Rome

- Author:

- Publisher:The Lilliput Press

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

North of Naples, South of Rome: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "North of Naples, South of Rome" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

North of Naples, South of Rome — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "North of Naples, South of Rome" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Chris and Diane

Thanks to John and Isabella for their encouragement,

Paul and Kathy for keeping me mobile,

and my wife for being there

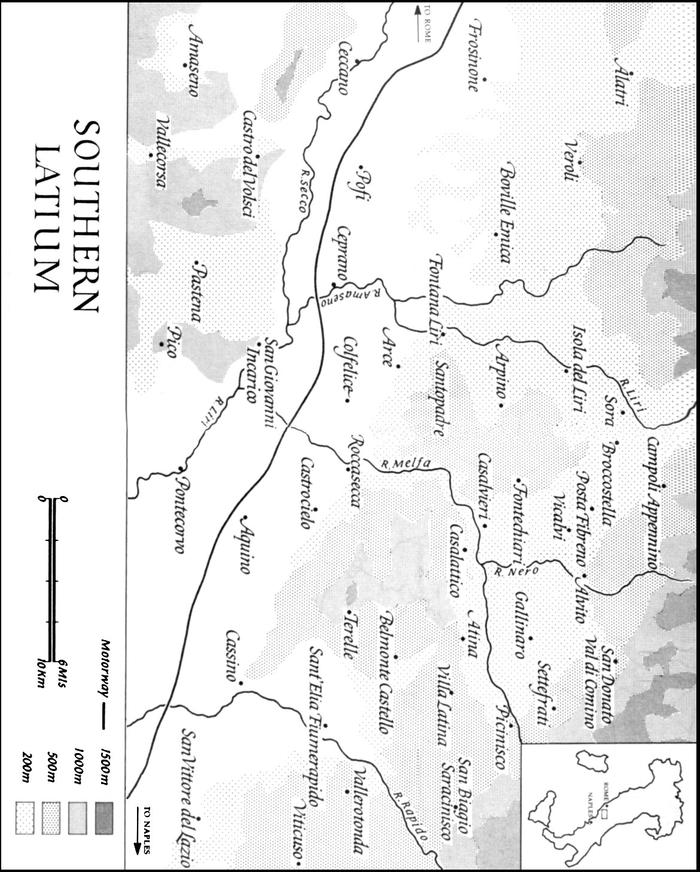

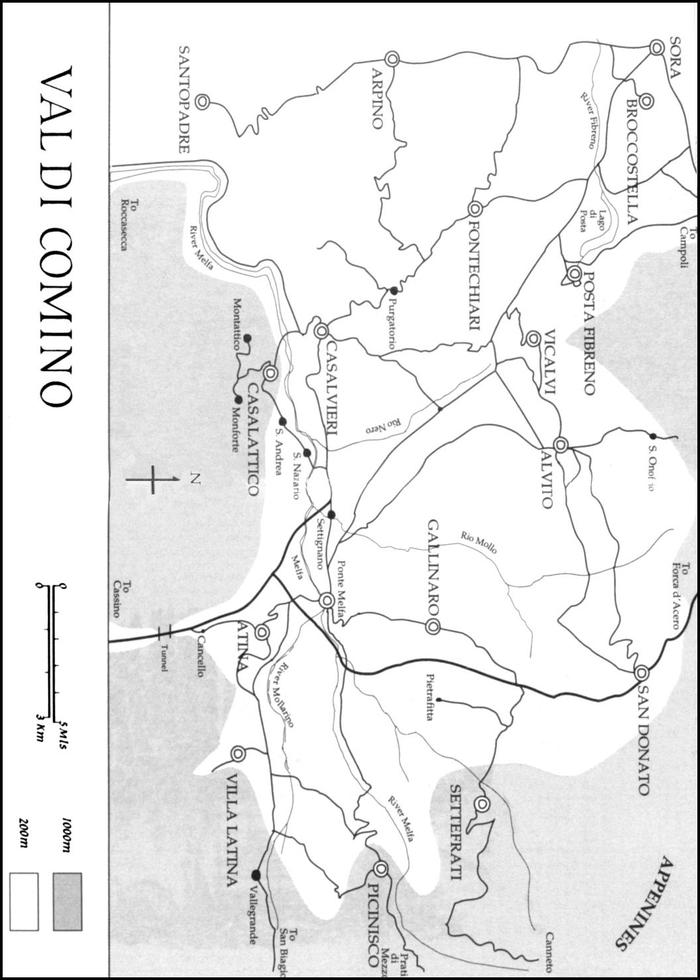

This is not a book about Italy; it is about the Comino Valley in Lazio. The valley is, none the less, inhabited by Italians who have a lot in common with those who live outside the valley. In fact, they have so much in common that it is tempting to assume that all of Italy works in much the same way as the valley does.

It is a big valley nearly a fifth of the province of Frosinone. A man could spend much of a lifetime discovering what is worth knowing about its dozen towns. It is big enough to be a world in itself; a simple man could find all he needs within it.

There is no escaping the fact that my viewpoint is provincial, and when the focus is on Gallinaro, my home town, it becomes distinctly parochial. Still, this valley is my Italy; I know it well, and am related to a huge number of its inhabitants. Historically, this was not a rich world; predominantly agricultural, its wealth has always been wine and oil. Unlike Tuscany, the valley contains no large reservoirs of art or culture, it has no beaches, no cathedrals and no tourists. Until recently, large numbers of its inhabitants emigrated to Europe, the Americas and the Antipodes. No one ever came here, they just left.

Lurking within this undisturbed territory is, of course, the real Italy. People from all over the peninsula lay claim to living in the real Italy, but they are wrong. The real Italy lies here, in the Comino Valley, north of Naples, south of Rome, high in the mountains, surrounded by the Apennine peaks.

My father was born in 1918 in Gallinaro, one of the twelve villages in the Comino Valley. His father, Luigi, had the dubious distinction of being one of the last soldiers to be killed in the First World War wounded on 10 November 1918 and dying three days later, six months before my father was born. My grandmother Luisa, young and pretty, refused two offers of marriage and brought up my father and his elder brother by herself. Luigi left her a large house in Gallinaro, which she converted into a petrol station, a bar and a grocery shop. The house is at the bottom of the hill on which Gallinaro stands and on what was then the main road across the valley, so the business prospered.

My father was a good student and won a scholarship at the age of seven to Frascati College, in the Alban Hills, to the south of Rome. It was a boarding school, where the students had only the summer holidays to spend at home. Here he excelled at Latin and Greek, but a year before his baccalaureate he was expelled for bringing a girl to his rooms when it was discovered, despite his protestations, that she was not in fact his cousin. This was a serious blow, since he now had to find a new school with only a year until his university entrance. After nearly ten years at Frascati, he attended his last year of high school at the Tulliano, the classical lyce in Arpino, an old city just beyond the confines of the Comino Valley.

Luisa, my fathers mother, was not from Gallinaro originally. She came from the village of Casalattico, another of the villages in the valley. Her family, the Fuscos, were farmers in the hamlet of San Nazario. Since the middle of the last century pieces of the farm had been sold off bit by bit family history has it that this was to cover gambling debts. As it grew smaller, it was no longer able to support the two large families that then worked it. By the turn of the century two brothers, Benedetto and Francesco, had divided the house, and each brother had seven children. Luisa, my grandmother, was the youngest child of the elder brother.

Mario, the eldest child of the younger brother and Luisas cousin, decided that prospects on the farm were far from good and so he emigrated with two of his brothers to Scotland, but not before the three brothers had married the three Magliocco sisters. Mario had two daughters, the elder of whom, Irene, he sent to school in Italy, where she lived with her aunt Rosa in Casalattico. After returning to Scotland for two years, Irene went back to Italy to the College of Santa Giovanna, in Arpino, where she met my father, Dionisio , her second cousin.

Nuns, being what they are, ensured that contacts between their female charges and the outside world were as short and as sporadic as possible, so it was not until my mother and father were visiting their respective halves of the family house in San Nazario that their romance blossomed. But then came the war. My mother returned to Scotland, while my father studied law at the University of Florence. They corresponded as frequently as they could, but towards the end of the war messages became harder to send. Its last years found my father as a second lieutenant in the Italian army, hiding from the Germans in the mountains surrounding the Comino Valley. The house in San Nazario had been taken over by the Germans as a billet, while a house my father had inherited in Gallinaro was also requisitioned. The Comino Valley was for eighteen months part of the Gustav line holding Cassino, so the density of German troops in it was high.

When Cassino finally fell, the Germans left the valley and the rebuilding began. In Italy it is traditional on New Years Eve to set off bangers and fireworks. My father told me that New Years Eve 1944 was quite a sight. All around the valley people had collected the detritus of war and saved it for the celebrations. The sky was alight with tracer bullets, machine guns fired, grenades exploded and high above Casalattico someone pounded the sky with a howitzer. For years afterwards , my great-aunt had a stack of explosives little cakes about the size of a bar of soap with a hole in the middle, presumably for a detonator. She used them for firelighters. That year everyone in the valley was well armed. The new government was nervous of the strength of the former resistance fighters. My father and his cousin Dino were armed by the government and given a small arsenal to distribute to trusted friends and relations if the expected rebellion ever happened. In 1946 my father was elected mayor of Casalattico, the youngest ever and almost certainly the first with a degree.

In Scotland in 1947 my mother was making preparations to marry a nature-cure practitioner. Shortly before the wedding date my grandfather took her to Italy to visit their relations, since the war had disrupted communications between them for six years. Naturally, while in Casalattico, my mother met my father again and their romance started anew. On her return to Scotland the impending marriage to the Scot was called off with three weeks to go, gifts were returned and a new wedding planned. Shortly afterwards my father, disillusioned with post-war Italy, came to Scotland to marry my mother. I was born in 1949 and, although I spoke only Italian until I was five, English became my first language.

I suppose early experiences have profound effects. Like my father, I was sent to boarding school at the age of eight, a decent Catholic preparatory school in Worcestershire. Although I have happy memories, I can also remember how frequently I was told that We won the war. This was often accompanied by a dig in the head and, truth to tell, never made me feel very English. The differences in culture were never more apparent than on visiting days, when my father was apt to kiss me. Whereas a kiss from a mother was just about tolerated, a kiss from ones father was definitely suspect, if not damn foreign.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «North of Naples, South of Rome»

Look at similar books to North of Naples, South of Rome. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book North of Naples, South of Rome and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.