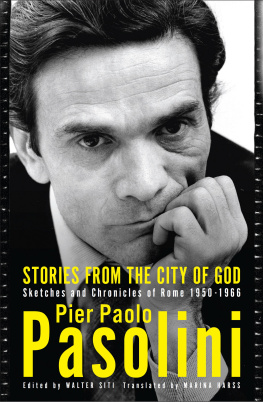

PRAISE FORSTORIES FROM THE CITY OF GOD

The essays or chronicles in this collection are slight but marvelouspowerfulmovingIn Marina Harsss lively translation, these chronicles are more concrete and colorful than the furious polemics of Pasolinis last yearsto which they make an excellent prelude.

The Nation

Whats ugly and squalid shows its beauty to PasoliniThe short pieces succeed as portraits of people and place during a certain timeThe author opens up a window on hidden Rome, a part of the city that continues to exist in certain dodgy corners and presumably always will.

Bloomsbury Review

The pieces in this collection suggest watercolor portraits of Rome and Romans as they were when Pasolini first moved to the city in 1949a gorgeous account of Pasolinis itinerary, migrating between zones of cultural privilege and the lower depths.[T]hese occasional writingssome outtakes from his novels, others written for newspapers and journalsare suffused with an ecstatic love for the wiles and mannerisms, urban patois, and unconscious grace of the underclass. Pasolinis lightness of touch and breadth of observation combine in a gestural prose with a revolutionary purpose.

Film Comment

Ebook ISBN9781590519981

A paperback edition of this book was published in Italian under the title Storie della citt di Dio; Racconti e cronache romane (19501966).

Copyright Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1995

Translation copyright 2003 Marina Harss

Production Editor: Robert D. Hack

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

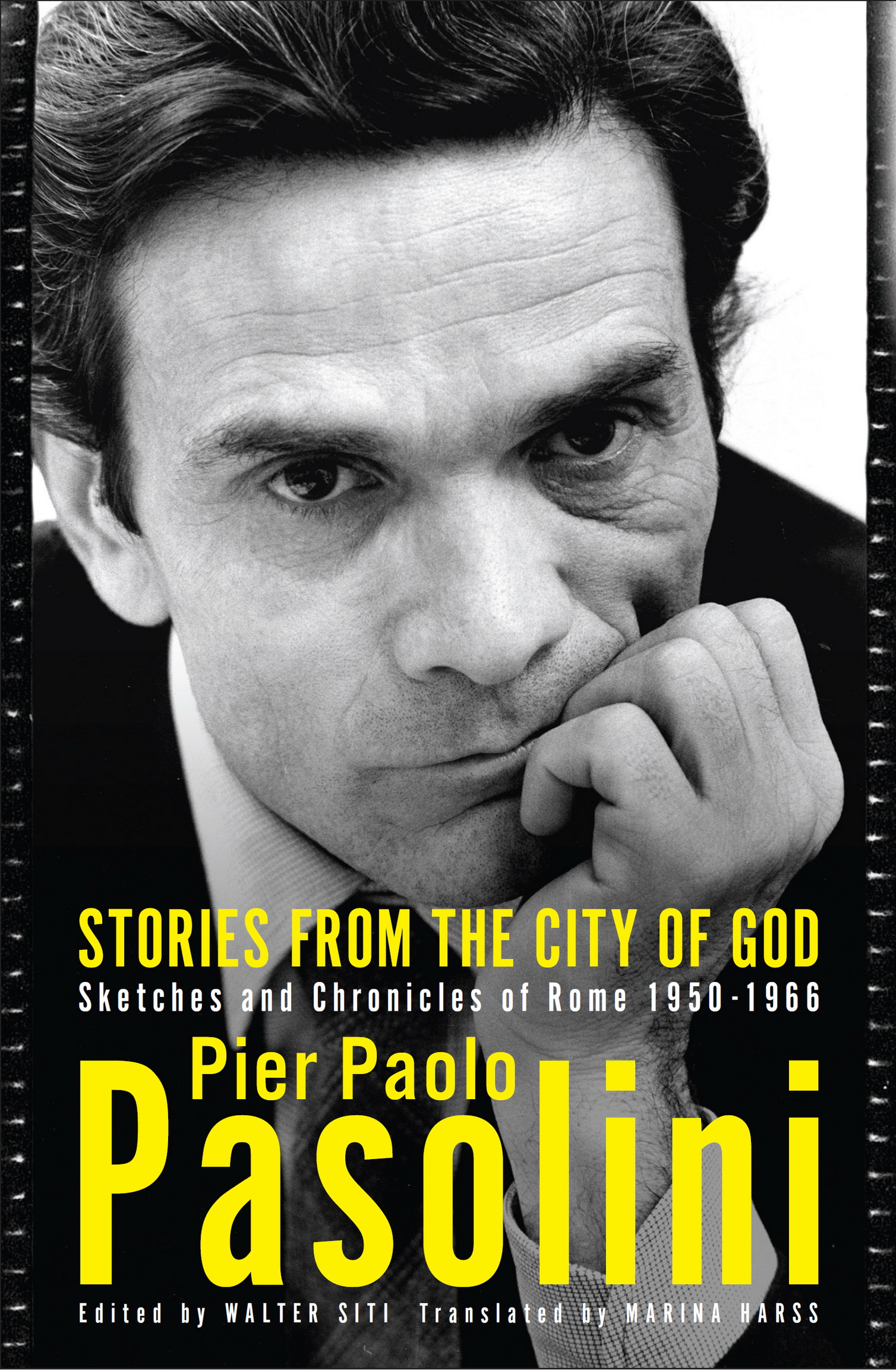

Pasolini, Pier Paolo, 19221975.

[Storie della citt di Dio. English]

Stories from the city of God : sketches and chronicles of Rome, 19501966 / Pier Paolo Pasolini; translated by Marina Harss.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-59051-048-8

I. Harss, Marina. II. Title.

PQ4835.A48S7613 2003

853.914dc21

2003040462

v5.4

a

CONTENTS

TRANSLATORS NOTE

In the winter of 1949, I fled with my mother to Rome, as in a novel. This is how Pier Paolo Pasolini later described, with his characteristic sense of drama, his move to Rome at the age of twenty-seven. With his escape from northern Italy, his Roman adventure began. A sexual scandal had destroyed his Friulian idyll, the first of a long series that would plague his life. He had spent his entire youth in the northern countryside, shielded to a great degree from the violence and repression of the Fascist regime, the war, and the subsequent destruction and poverty Italy experienced in this period. Yet once in Rome, he found himself poor and alone save for his beloved mother, in a city ravaged by war and then undergoing a period of intense change. He found his new home among the underprivileged, peripheral, marginalized classes who lived in the new projects built on the outskirts of the city, and in its ancient, rough, lower-class neighborhoods. He was witness to the beginning of a process that would transfigure the city into a modern, gentrified capital, a process that he feared and loathed and that finally drove him away. In his interview with Luigi Sommaruga that is included in this volume, Pasolini expresses his break with Rome in terms reminiscent of the end of a love affair: It has changed, and I dont want to understand it any more.

In this volume, we detect an emotional cycle that begins with the shock of freedom and love that Pasolini felt when he first arrived in Rome and concludes with the disgust, sadness, and alienation that he felt toward the end of his life. At his first encounter with the city, he was deeply moved and fascinated by the contrasts and layers that were, and to a degree still are, its most defining feature. In Roguish Rome, he writes, Its beauty is a natural mystery. We can attribute it to the stratification of styles which at every angle offers up a new, surprising cross section; the excessive beauty produced by this superposition of styles is a veritable shock to the system. But would Rome be the most beautiful city in the world if it were not, at the same time, the ugliest? When he speaks of beauty and ugliness, he is not simply evaluating architectural styles. What matters to Pasolini, the only thing that truly matters, are the people living in its various neighborhoods, slums, projects, and shantytowns. The beauty is to be found in the Roman ragazzo as well as in the sweep of the Tiber, and the ugliness lies in the torpor of the slums and the squalid lives of the people who live in them, and even more in the greed, oppression, and American-style commercialism that he sees taking over his beloved city and the whole country. For him, the greatest ugliness of all lies in the hypocrisy of power in all its forms, domestic and political. Thus a sense of place defines and completely infuses the mentality and attitudes of the people whose lives he witnesses, and both tentatively and passionately participates in.

Pasolinis vision of the city, then, is his portrait of its poor and marginalized, among whom he lived. They are people like Morbidone in The Passion of the Lupin-Seller, or the young man selling chestnuts by the Trastevere bridge in Trastevere Boy, and the boy who steals fish from the market in The Dogfish. At first, the author is drawn to these characters by need, as he admits in The Periphery of My Mind. It was need, my own poverty, even if it was that of an unemployed member of the bourgeoisie, that drove me to the immediate human, vital experience of the world which I later described and continue to describe. I did not make a conscious choice, but rather it was a kind of compulsion of destiny. Beyond this, Pasolini feels an enormous admiration for their ability to prevail against the onslaught of modern bourgeois culture that pushes them further and further toward the fringes. This affection, even love, tinged with erotic attraction, fascinates him with the inner working of the minds of his characters as if they held the key to a sublime understanding. He writes of the chestnut-seller in Trastevere Boy, For my part, I would like to understand the mechanisms of his heart by which the Trastevereshapeless, pounding, idlelives inside of him. Where does the Tiber end and the boy begin?

His answer is language, and in particular, dialect and slang. Pasolinis discovery of dialect marked a crucial moment in his youth, an awakening. This awakening occurred during the war, when he was nineteen and living in his mothers rural home town of Casarsa in Friuli. I learned Friulian as a sort of mystical act of love, he said later in a 1969 interview. It became an almost religious, self-defining impulse to learn the local dialect and render a version of it in his writing. Through language, he deciphered a mysterious connection to the closed, pre-Christian world of the Friulian peasants, their relationship to nature and the outside world, and eventually, through an erotic relationship with a local boy, to his own sexuality. This experience of discovery would be repeated and expanded with the Roman underclass. In Casarsa, he began writing poetry and narrative sketches in Friulian dialect. At the time, his use of dialect was also a political statement; he was writing in a lower form of Italian at a time when the classical, heroic origins of Italian culture were being championed by the Fascist regime, which tried to suppress the identities of all subcultures and differences for the sake of national unity and the consolidation and centralization of power. For personal, esthetic, and political reasons, Pasolini instinctively placed himself on the outside, with the people he loved and their anomalous landscape and way of life. He was, at the same time, extremely self-conscious about his relationship to his chosen subjects and the use of their language. This operation of transcription of dialect was a conscious act and a political one, one that he knew might appear forced and artificial to his critics. His novels,