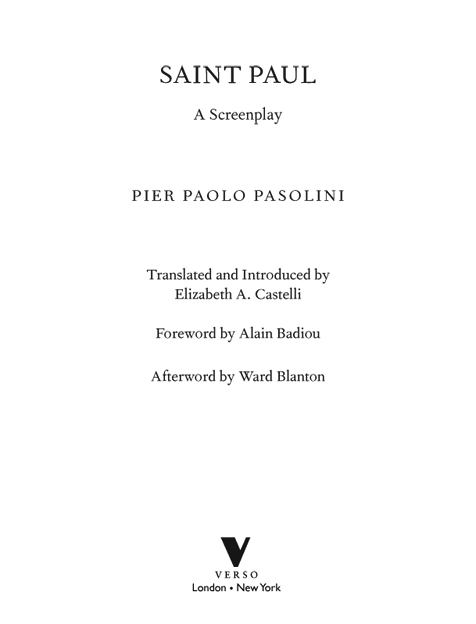

This English-language edition first published by Verso 2014

Translation Elizabeth A. Castelli 2014

Foreword translation David Fernbach 2014

Introduction Elizabeth A. Castelli 2014

Afterword Ward Blanton 2014

First published in Italian as San Paolo

Einaudi 1977

Foreword first published in the French edition, Saint Paul

Foreword Editions Nous 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-288-3 (HBK)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-289-0 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-658-4 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

Contents

Foreword

Alain Badiou

It is well known that the Christian reference played a role of primary importance in the formation of Pasolinis thought, despite (or because of) the sexual and transgressive violence that inspired his personal life and bestowed a particular coloration on his communist political choices. In a certain sense, it was a sacrifice bordering on the sacred the mysterious death of his brother, an Italian partisan, probably killed by the Yugoslav resistance at the moment of Liberation that led both to his view of the judgement one can make on History, and to the severity he displayed, from the late 1950s on, towards the Italian Communist Party. Basically, the PCI was guilty in his eyes of having allowed the young people of the Resistance to die without legitimate heirs or genuine political paternity, which led also to abandoning to their fate the young proletarians of the modern housing estates. Among other texts, the broad and splendid poem Vittoria presents the history of this denial, suggesting in the background the denial of St Peter: by denying Christ, Peter had shown too much attachment to his own safety; and against Paul, at Antioch, too much attachment to the old rituals that limited the universality of the message. It was Peter, rather than Paul, who prefigured the sclerosis of the Church, and likewise that of the PCI. Consider this passage, which stigmatizes the realism of political parties, caught in the mysterious debate with Power and deaf to the voice of young people in revolt:

Joyous

with a joy that rejects any second thought

is this army blind in the blind

sun of young dead, who come

and who await. If their father, their leader,

leaves them alone in the whiteness of the hills, in the peaceful

plains absorbed in a mysterious debate

with Power, enchained to its dialectic

that history forces him unceasingly to reform

quite gently, in the barbarous hearts

of the sons, hatred gives way to love of hate.

More generally, Pasolini relentlessly confronted the forms that a life devoted to the naked truth of the subject could take vis--vis the avatars of the Passion and the pitfalls of holiness. If we compare him, for example, with Bataille, it is easy to maintain that it is with much more sincerity, exposure to risk, and poetic gift that Pasolini made the dialectic of abjection and the sublime his own. If we compare him with Genet, we have though in this case equal in terms of quality the whole difference between sublimation by way of poetry (or the cinema) and sublimation by way of prose (and the theatre). The former orients itself towards origins, fables and myths, the figures of history (Oedipus, Christ, St Paul, Dante, Gramsci) the latter to an intimate tale mingled with and borne up, as it were, by the latent breath of the history of peoples: underclass prison angels, prostitutes, blacks, Palestinians But in every case, on the horizon of meditation lies the question of religion. Not as a possibility still open, there is no question of believing in it, but as a poetic and historical paradigm of the possibility of scathing confrontation, at the heart of individual and collective existence, with the implacable truths that religion can express and with the meaning it may or may not receive from the world such as it is.

It is indeed this rift between meaning and truth that is at issue in the figure of Oedipus, as Pasolinis very fine film restores him: as soon as one discovers the truth (murder of the father, incest with the mother), the only meaning that life still finds is in blindness and death. But this is also the figure of Christ: so that truth will come to the desert world of men, God must present the absurdity of his own torment. Hence the power of the film that Pasolini drew from the Gospel According to St Matthew. And is it not tempting to see Pasolinis own death, which remains so obscure, as the Passion of true desire fulfilled in sacrifice under the insensate knife of the person this desire encounters?

It is only too natural, in this context, that St Paul should have been a tutelary figure for Pasolini. He saw him, in fact, as the first embodiment of the conflict between political truth (communist emancipation being the contemporary form of salvation), and the meaning this could assume in the weight of the world. In our world, in fact, truth can only make its way by protecting itself from the corrupted outside, and establishing, within this protection, an iron discipline that enables it to come out, to turn actively towards the exterior, without fearing to lose itself in this. The whole problem is that this discipline (of which Paul is here the inventor under the name of the Church, like Lenin for communism under the name of the Party), although totally necessary, is also tendentially incompatible with the pureness of the True. Rivalries, betrayals, struggles for power, routine, silent acceptance of the external corruption under the cover of practical realism: all this means that the spirit which created the Church no longer recognizes in it, or only with great difficulty, that in the name of which this was created.

Paul is one of the possible historical names of the tension between fidelity to the founding event of a new cycle of the True (metaphorically, the resurrection of Christ; actually, the communist revolution) and the rapid exhaustion, under the cross of the world, of the pure subjective energy (holiness, or totally disinterested militancy) that the concrete realization of this fidelity would demand.

Pasolini wanted to make a major film on the dialectical character of Paul. This would essentially be a sequel to his film on the Passion of Christ: the history of the Church, which, as guardian of the meaning of this Passion, propagates and perpetuates its truth effects, and also the history of the failure of this guardianship. He did not find financing for this film. But we have a very detailed scenario of it, a scenario that in my view is in itself a literary work of the first magnitude.

As he did in his Oedipus Rex, Pasolini juxtaposed the ancient reference with the contemporary, but in a very different manner. The action of Saint Paul, in fact, is situated completely in the contemporary world, whereas in Oedipus Rex, the contemporary drama with the mother duplicates the connected visibility of the legendary tale. What pertains totally to antiquity in