credits

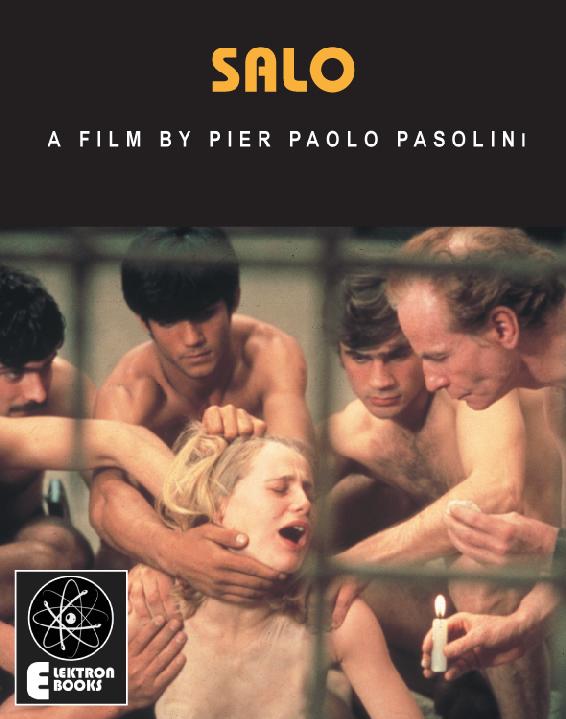

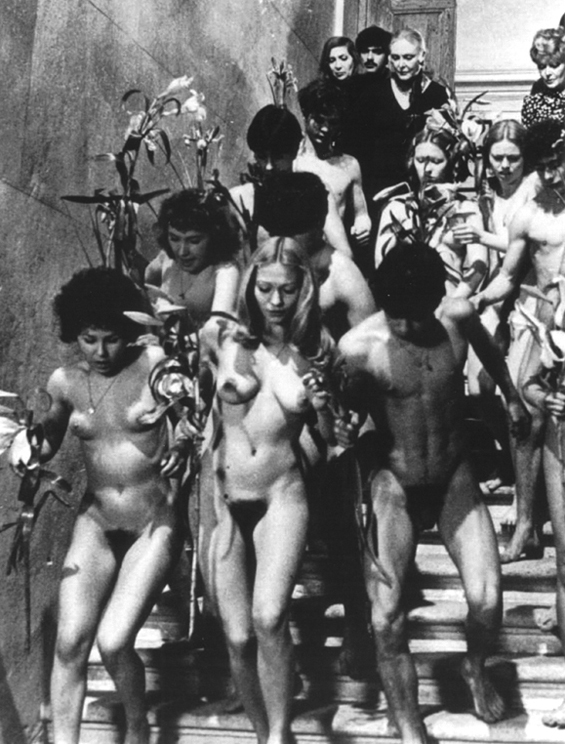

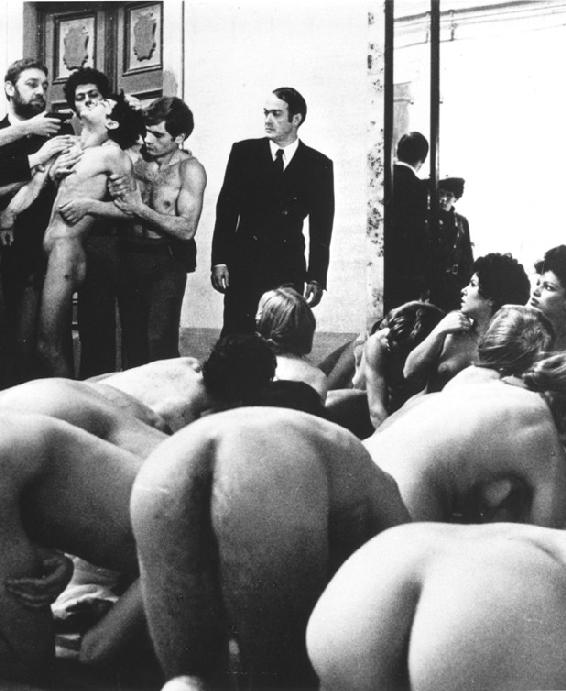

SALO: A FILM BY PIER PAOLO PASOLINI

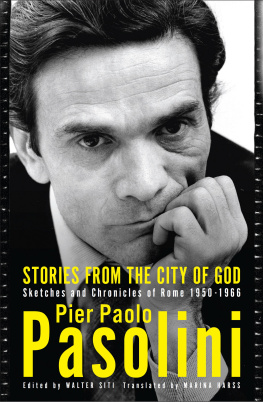

BY STEPHEN BARBER, PIER PAOLO PASOLINI

AN EBOOK

ISBN 978-1-908694-04-1

PUBLISHED BY ELEKTRON EBOOKS

COPYRIGHT 2011 ELEKTRON EBOOKS

www.elektron-ebooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a database or retrieval system, posted on any internet site, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holders. Any such copyright infringement of this publication may result in civil prosecution

PASOLINI AND SADE: A MALEFICENT OBSESSION

1 : Ante-Inferno

Sal is the unique space where film terminally collides with death.

Death does determine life, I feel that, and Ive written it, too, in one of my recent essays, where I compare death to film-montage. Once life is finished, it acquires a sense; up to that point it has not got a sense; its sense is suspended and therefore ambiguousFor me, death is the maximum of epicness and myth.[1]

Pier Paulo Pasolini, 1968

2 : Circle of Obsessions

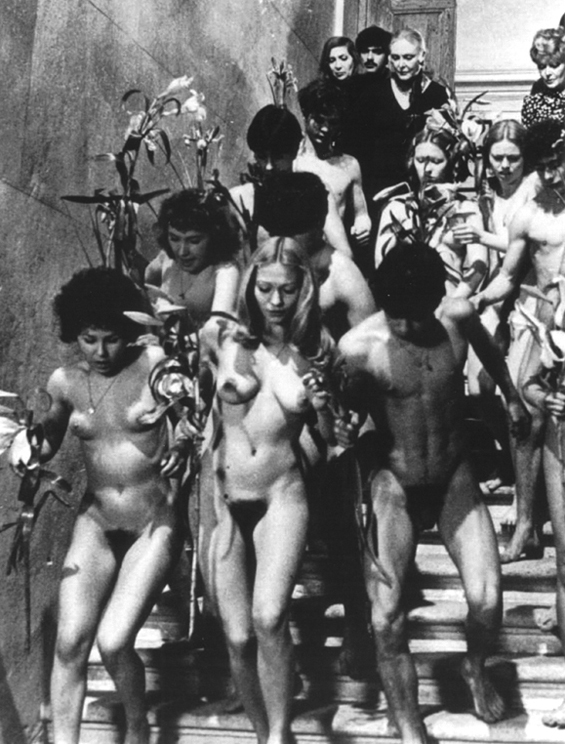

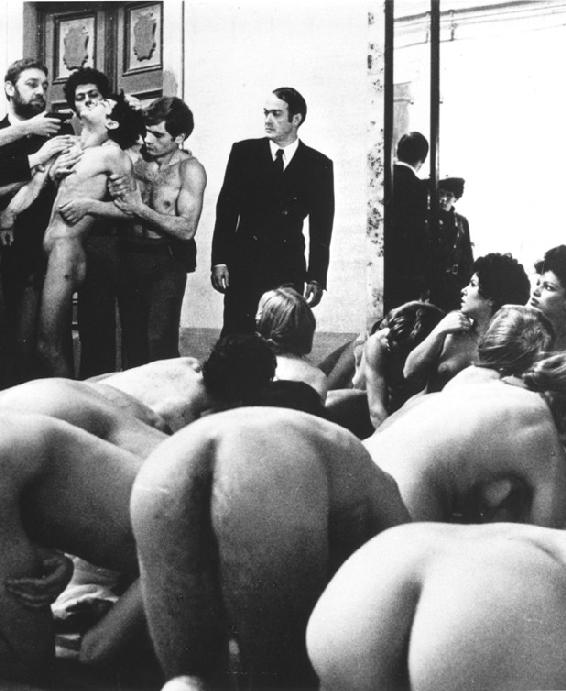

During the production in 1975 of what would be his ultimate film, Sal adapted from Sades novel 120 Days of Sodom and transposed to the final moments of the fascist dictatorship in mid-1940s Italy the film-maker and poet Pier Paulo Pasolini often asserted that he wanted that film to be the last movie[2]: not only his own last movie, but also that of the entire human species: a film of terminal images, before the processes of cultural and social erasure which Pasolini incessantly denounced had engulfed and nullified the visual image entirely. The images of Sal revelatory of the structures of cruelty and of the sexual origins of human atrocities and massacres would then form a kind of malign legacy, left for any non-human species which, at some point in the future, might want to look back upon the memories and obsessions of the human species. The concept of the last film was one that attracted many other film-makers during the era of tumultuous upheaval, revolutionary terrorism and worldwide violence that extended from the mid-1960s to the late-1970s; in the USA, the actor-director Dennis Hopper had already adopted that notion of a last movie for the film-title of his seminal, drug-disintegrated masterwork of 1971. However, Sal was not the first Pasolini film to be conceived of as a terminal exercise; like his contemporary, the West German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Pasolini was perpetually announcing his abandonment of film-making, while simultaneously planning another film-project that would push beyond the extreme limit of his current film. Similarly, the novelist Jean Genet a profound source of inspiration for Pasolini declared in The Thiefs Journal (1949) that it would be his last novel, then asserted in that novels final two sentences that it would, after all, have a sequel (which never actually transpired). For Pasolini, that film beyond-the-end was to have been a project entitled Porno-Teo-Kolossal , which was in preparation to be shot, in New York, Naples and Paris, in the first months of 1976, based on a 75-page film-treatment largely composed of dialogue. However, whether by chance or intention, Sal would mark the very end of Pasolinis work shortly after he had finished editing it, he was savagely murdered by a boy-hustler whose penis he had been sucking only minutes earlier.

Sal was a terminal aberration in Pasolinis work. Unusually, he took on a project which he had not developed himself; his collaborator Sergio Citti had initiated the project, intending to direct it himself, but could not find a producer for it. Pasolini had no difficulty in attracting the producer Alberto Grimaldi, who had had an immense success with Last Tango in Paris , directed three years earlier by Bernardo Bertolucci. Once Pasolini had taken on the project, at the beginning of 1975, he researched it intensively; alongside Sades own work, he read essays on Sade by Georges Bataille (notably, Batailles preface to Sades book), Roland Barthes, Pierre Klossowski and Maurice Blanchot, as well as conducting research into the last phase of Italian fascism. And in August 1975, following the films shooting-period, he would meet with the Surrealist artist Man Ray, who had painted an imaginary portrait of Sade in 1938; Pasolini was contemplating using the portrait on posters for his film.

The Marquis de Sades 120 Days of Sodom details the acts of four atheistic Parisian libertines who possess the wealth and power to realize a plan to have sixteen aristocratic young boys and girls kidnapped from their homes, and brought to an isolated castle in Switzerland, the Castle of Silling; accompanied by four story-tellers and eight well-endowed cockmongers, the libertines spend four months inflicting an escalating series of sexual tortures on the boys and girls, before finally slaughtering them and returning to Paris. The boys and girls to be massacred are all selected for their exceptional beauty (especially that of their rear-ends), for their young age (between twelve and fifteen), and for their social origins: Augustine, for example, is described by Sade as fifteen years old; daughter of a Languedoc baron, with an alert and pretty face[3]. Sade completed his account of the first of the four months, November, while imprisoned for acts of debauchery at the Bastille prison in Paris in 1785. However, the remaining three parts of the book (for the months of December to February) were only written in the form of notational drafts: skeletal enumerations of the acts undertaken by the libertines, and cryptic summaries of the accompanying story-tellers narratives. It appears that Sade intended to publish the first part of the book separately, and then to complete each of the three other parts as the publication progressed; however, the manuscript, written on a long scroll of paper, was lost during the revolutionary riots of 1789, and only re-discovered in the early twentieth century. The French Revolution changed Sades fortunes: released from the Bastille, he initially became a revolutionary judge (though a lenient one, who rarely condemned anyone brought before him), but then fell into poverty and ended his life in the benign incarceration of the Charenton asylum-hospital, on the edge of Paris.

Pasolini moved the action of the novel in time, to the period 1944-45, thirty years prior to the moment of the films making. He also moved the action geographically, from an impregnable, mountain-top castle in Switzerland to a salubrious lake-side villa in the small resort town of Sal, overlooking a bay on the Riviera Bresciana, on the banks of Lake Garda in northern Italy. It was in Sal that the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini (who had held power since the year of Pasolinis birth, 1922) established his short-lived Republic of Sal with his remaining supporters. Although Mussolini does not appear as a character in Pasolinis film, his desperate, extreme situation of that period is omnipresent; his Republic of Sal was a final pocket of fascism, ready to defend itself at all costs, by acts of atrocity, after the Italian government had concluded a surrender with the British and American forces, thereby changing sides in the last phase of the Second World War. The Italian government had then deposed and imprisoned Mussolini in 1943, confining him to a hotel on the inaccessible peak of the Gran Sasso mountain in the Abruzzo region, east of Rome, expecting to be able to try him at the end of the war; but Mussolinis friend and ally, Adolf Hitler, was determined to rescue Mussolini from Gran Sasso, and dispatched his best pilot to land on the mountain-peak and spirit Mussolini away to the Lake Garda region, which was still held by the German forces. Mussolini was then installed as the dictator of the northern part of Italy still under the control of the Germans, while the invading British and American forces were rapidly advancing northwards through Italy, after landing in Sicily. As that advance reached the north, Mussolinis chaotic Republic of Sal quickly disintegrated; on the run from partisans, he was captured and cursorily machine-gunned to death in April 1945, in a village alongside Lake Como, then hung upside-down, alongside his mistress, in the Piazzale Loreto in Milan. News of the ignominy of Mussolinis killing led Hitler to commit suicide, in order to avoid meeting a similar fate, as Josef Stalins Soviet army closed-in on Hitlers own headquarters in Berlin.

Next page