THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR JAPANESE STUDIES

MICHIGAN PAPERS IN JAPANESE STUDIES

NO. 6

SUKEROKUS DOUBLE IDENTITY: THE DRAMATIC STRUCTURE OF EDO KABUKI

Barbara E. Thornbury

Ann Arbor

Center for Japanese Studies

The University of Michigan

1982

ISBN 0-939512-11-4

Copyright 1982

by

Center for Japanese Studies

The University of Michigan

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-939512-11-9 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12794-8 (ebook)

ISBN 978-0-472-90190-6 (open access)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I would like to thank the Japan Foundation, Canada Council, and Killam Fund for Advanced Studies for supporting me in the research and writing of this work.

My thanks go especially to Professors Leon Zolbrod, Matsuo Soga, and Andrew Parkin of the University of British Columbia.

I am also very grateful to Professor Gunji Masakatsu of Waseda University, Hattori Yukio of the National Theater of Japan, Karen Brock of Princeton University, and Mayumi Sakuma of Ochanomizu University.

My deepest gratitude is to my husband, Don.

This book is a study of traditional, Edo kabuki. Its aim is to show that the seemingly illogical double identity of the townsman, Sukeroku, and the samurai, Soga Gor, in the play Sukeroku is a surviving element of what was once a complex and coherent structure based on a traditional performance calendar.

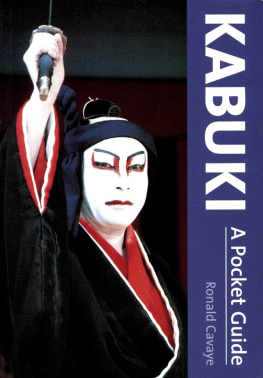

Kabuki was the principal dramatic form and a mainstay of urban popular culture during the Tokugawa period. A large number of the practices which characterized kabuki during that time are still carried on today. Many, however, were abandoned in the last half of the nineteenth century, when Japan embarked on her course of modernization.

Perhaps the most important practice to be left behind was strict adherence to a traditional theater calendar, or shibai nenj-gyji. The calendar consisted of four seasons, corresponding to four major production periods. These were the kao-mise, or face-showing, production beginning in the eleventh month of the lunar year; the spring or New Year production which followed in the first month; the bon festival in the seventh month; and the farewell production, which brought the theater year to a close in the ninth and tenth months. The calendar was generally the same in Edo and Kamigata (Kyoto-Osaka) kabuki, but there were differences in the dramatic conventions of the two regions. The focus of this work will be on Edo, which came to be the center of culture in the Tokugawa period. It is also the place that is associated with Sukeroku.

The calendar provided the framework of kabuki. Kabuki was composed of a series of relatively short plays which were arranged and even rearranged during each production period according to the dictates of dramatic convention (especially those connected with seasonal change) and audience response. Kabuki was not regarded as a random collection of single plays, but rather, plays were seen as standing within the framework of the traditional calendar as a whole. The calendar was so crucial that unless its role is understood aspects of certain plays that survive in the present-day repertory, such as the double identity in Sukeroku, do not make sense.

Sukeroku is a major work of kabuki. Performed for the first time in 1713 by Ichikawa Danjr II, it flourishes today as one of the jhachi-ban, or eighteen favorites. Thus, the history of Sukeroku spans more than two hundred and fifty years, beginning when kabuki was just emerging as a major dramatic art form and continuing until the present when it is being kept alive by Japanese awareness of and reverence for great art forms of the past.

To show how the calendar functioned and what Sukerokus double identity signifies, the book is divided into two parts. studies the structure of Edo kabuki. The first chapter, which outlines that structure, is based for the most part on writings of the Tokugawa period. The second chapter then looks at the concepts of sekai, tradition, and shuk, innovation. Kabuki was the product of material that had become a familiar part of Japanese culture by repeated use and dramatization over long periods of time, starting before kabuki began, and material that was relatively new and was used to transform the older, set material. The double identity in Sukeroku came about as a result of this interplay between what was received by way of tradition and what was added by way of innovation.

, the discussions of kabuki are limited to Ichikawa Danjr I and his son, Danjr II, since their work was the basis of all later developments.

During the Tokugawa period kabuki was annually divided into four major production periods, comprising altogether about two hundred days of performance time.

| PRODUCTION | STARTING DATE |

| kao-mise (face-showing) | 11th month, 1st day |

| spring | 1st month, 15th day |

| bon (refers to bon festival) | 7th month, 15th day |

| farewell | 9th month, 9th day |

Strictly speaking, two more periods can be added: the third-month and fifth-month productions, beginning, respectively, on the third day of the third month and the fifth day of the fifth month. These, however, were usually part of the long-run spring production and will be treated as such here.

The theater year opened on the first day of the eleventh month, two months before the civil new year. No one knows for certain why this schedule was adopted, but it may go back to an historical relationship between drama and the agricultural cycle. Customarily, the eleventh month is the time to offer newly-harvested rice to the heavenly deities. In Japan, as elsewhere, the mythological beginnings of drama are in offerings to the gods. Thus, kao-mise, which began with three days of ceremonial dance-dramas, may be regarded as a successor of these ancient offerings to the gods.

As the theater new year, kao-mise was a festive occasion. For the three days of opening ceremonies audiences gathered early in the morning to watch the manager of the theater perform the principal role of the venerable old man Okina in Shiki Sambas. His heir and another relative or an apprentice played the supporting roles of Senzai and Sambas, This auspicious drama was the theater managements way of demonstrating support for the company.

Shiki Sambas is a variation of Okina, an ancient drama that is also found in but predates no. Okina represents a god in human form. In principle, this arrangement was not unlike that of kabuki.

During kao-mise Shiki Sambas was followed by a waki-kygen, or auspicious god play, the concept and terminology of which were probably borrowed from no. Because each kabuki theater had its own waki-kygen, producing them was an expression of the pride of the theater. Examples include: Shuten Dji at the Nakamura-za, Shichi-fukujin at the Ichimura-za, and Fukujin-asobi and the Morita-za. Both Shiki Sambas and waki-kygen were reserved for only the most special occasions, such as kao-mise, New Years, and the opening or reopening of a theater building.

Because n had a considerable influence on the early development of kabuki, it is natural to find features of resemblance in the two arts. Moreover, by preserving Okina (in the form of Shiki Sambas), for example, kabuki, which was viewed by the samurai (especially those who considered themselves proper Confucianists) as a rather undesirable activity of the commoners, could create a symbolic association with recognized and accepted conventions.

Starting on the fourth day of the new theater year, the dramatic portion of kao-mise was presented. It had two major sections, which can be subdivided as follows: