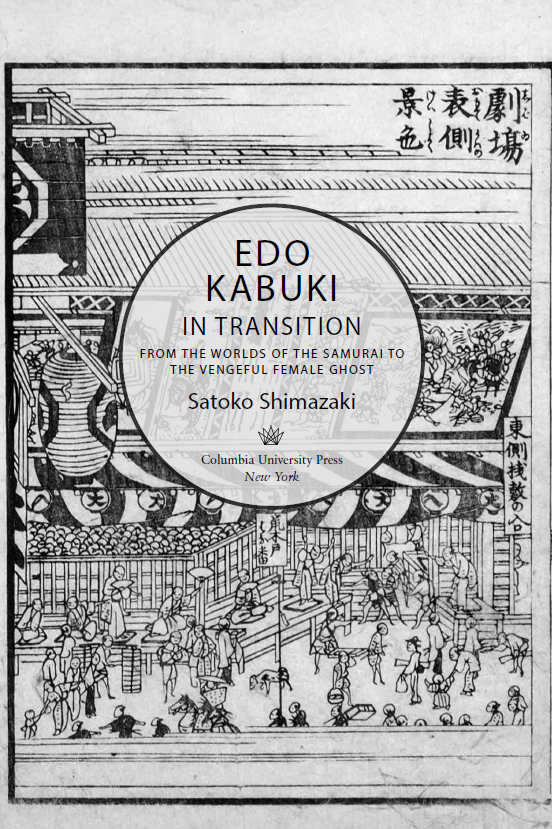

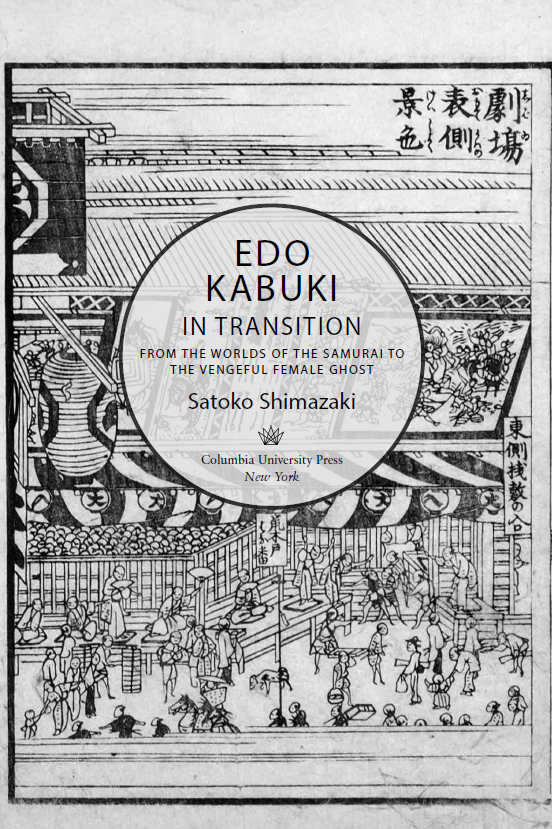

Edo Kabuki in Transition

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the AAS First Book Subvention Program and Waseda University toward the cost of publishing this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shimazaki, Satoko.

Edo kabuki in transition : from the worlds of the samurai to the vengeful female ghost / Satoko Shimazaki.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-17226-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-54052-0 (e-book)

1. KabukiHistory19th century. 2. Japanese dramaEdo period, 16001868History and criticism. I. Title.

PN2924.5.K3S365 2015

792.0952dc23

2015027593

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at cup-ebook@columbia.edu.

COVER DESIGN: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

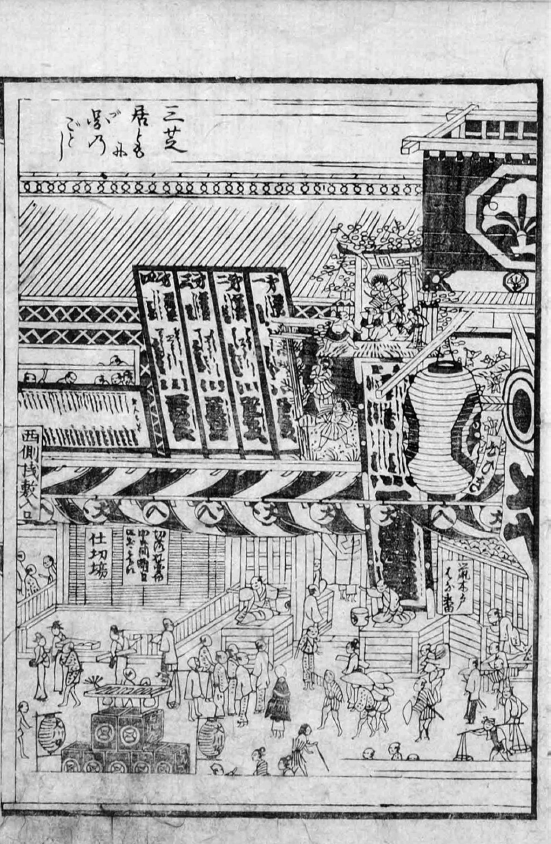

COVER IMAGE: (front) Courtesy of Waseda University Tsubouchi Memorial Theater Museum; (back) courtesy of the Idemitsu Bijutsukan, Tokyo

References to Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

Part I

The Birth of Edo Kabuki

[1]

Presenting the Past: Edo Kabuki and the Creation of Community

Part II

The Beginning of the End of Edo Kabuki: Yotsuya kaidan in 1825

[2]

Overturning the World: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers and Yotsuya kaidan

[3]

Shades of Jealousy: The Body of the Female Ghost

[4]

The End of the World: Figures of the Ubume and the Breakdown of Theater Tradition

Part III

The Modern Rebirth of Kabuki

[5]

Another History: Yotsuya kaidan on Stage and Page

As with most first books that result from years of training, research, writing, and revision, I am indebted to more institutions and individuals than I can name. I can offer only an incomplete list of the people whose generosity made it possible for me to produce this book, and an inadequate expression of my gratitude to them.

I would never have entered a graduate program in Japanese literature in the United States if I had not had the good fortune to spend a year at Middlebury College as an exchange student in political science from Keio University, and had John Elder not been kind enough to supervise a clueless young woman with no background in the study of literature in an independent study course on Japanese poetics. His passion and encouragement first made me realize that I might be able to pursue a graduate degree in a subject that I had always loved.

The time I spent at Columbia University as a masters and doctoral student was a stimulating period of discovery, exciting challenges, and sleepless struggles to learn to write academically in a foreign language. Haruo Shirane was the ideal adviser, who always expected the best from all his students and who was and continues to be the most generous and encouraging mentor possible. I know that I will never be able to duplicate his skills as I advise my own graduate students, though I certainly try. I was also fortunate to work with Tomi Suzuki and Paul Anderer, who taught me so much during my years as a graduate student and have remained incredibly supportive ever since. Henry David Smith II gave me excellent feedback on an early version of one of the chapters in this book that I wrote for one of his seminars, and Gregory Pflugfelder, Samuel Leiter, and Andrew Gerstle provided invaluable comments during my dissertation defense that continued to guide me as I prepared this manuscript for publication. My fellow students at Columbia made my time there enjoyable and memorable. There are too many of them to name here, but I remember in particular the many long conversations about research that I had with my roommate Young-ah Kwon. And even after graduation, I have been blessed with the friendship of Linda Feng and Chelsea Foxwell, who read parts of my manuscript and gave me helpful comments from the perspective of specialists in other fields.

During the two and a half years that I spent doing dissertation research in Japan, I was fortunate to be able to work with Furuido Hideo at Waseda University and Nagashima Hiroaki at Tokyo University. In particular, I learned an enormous amount from Furuido Hideos broad and deep knowledge of kabuki and his dynamic understanding of performance. I feel that everything I write is an attempt to fill in the outlines of ideas he has already intuited. I remember him telling his students never to miss a single kabuki productionadvice I have taken to heart and tried to follow whenever I am in Tokyo. My research would have been impossible without the knowledge and experience I gained through working with theater ephemera and prints as a participant in the Yakusha-e Kenkykai (Actor Print Workshop) at Waseda University. I am grateful to Akama Ry, Iwakiri Yuriko, Iwata Hideyuki, Kimura Yaeko, Matsumura Noriko, and e Yoshiko, among others, for sharing their expertise. taka Yji welcomed me into his seminar on yomihon at the National Institute of Japanese Literature, and Sat Satoru generously shared his knowledge of early modern illustrated fiction and his own collection of early modern books.

I continue to learn from students of theater and early modern literature with whom I studied in Tokyo, many of whom now teach at institutions in Japan. Umetada Misa, in particular, not only has been a great friend but has expanded my horizons and opened many doors for me during my dissertation research and beyond. This book would have looked very different without the help of people she introduced me to and the opportunities she created. Mitsunobu Shinya, Kuwahara Hiroyuki, Kaneko Takeshi, Matsuba Ryko, and Kurahashi Masae have also answered questions and helped me locate materials as I revised the manuscript of this book. Sat Katsura, Abe Satomi, and Kodama Ryichi have generously guided me to sources on modern kabuki, its actors, and the theater. Ellis Tinios, whom I first met when I was conducting dissertation research in Japan, has been a wonderful friend and mentor ever since. I have benefitted enormously from his generosity as a connoisseur of early modern prints and visual culture who is always eager to share his knowledge and the exciting materials he is continually discovering.

I had the good fortune to work with wonderful colleagues at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Janice Brown, Faye Kleeman, Matthias Richter, Antje Richter, and Laurel Rodd have all helped me in many different ways. I am particularly indebted to Keller Kimbrough, to whom I often turned for advice. Keller gave me many opportunities to grow as a scholar at an early stage in my career, inviting me to co-organize a joint conference and co-edit the volume that emerged from it. He also gave me excellent suggestions on my manuscript. At CU Boulder, I was also fortunate to work with Laura Brueck, Haytham Bahoora, Monica Dix, and CJ Suzuki, who formed a supportive community of young scholars.

The year I spent as a fellow at the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara, was instrumental in allowing me to make progress on my manuscript. I am especially grateful to Katherine Saltzman-Li, who made it possible for me to spend a year there. She not only gave me very useful feedback on my project at different stages but helped me in many ways both small and large that have led me to where I am now. Luke Roberts replied to various questions about early modern history whenever I turned to him. I am also very grateful for the friendship and guidance of Michael Berry and Suk-Young Kim, who have kindly invited me to share my research at UCSB on several occasions.

Next page