sentinel

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2021 by Helen Andrews

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Andrews, Helen (Millennial journalist) author.

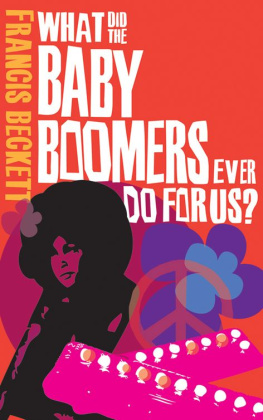

Title: Boomers : the men and women who promised freedom and delivered disaster / Helen Andrews.

Description: New York : Sentinel, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020036188 (print) | LCCN 2020036189 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593086759 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593086766 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Baby boom generationUnited StatesHistory. | Baby boom generationUnited StatesBiography. | United StatesHistoryBiography. | Liberty. | Generation YUnited StatesSocial conditions21st century.

Classification: LCC HN59.2 .A537 2021 (print) | LCC HN59.2 (ebook) | DDC 305.20973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020036188

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020036189

Cover design: Jennifer Heuer

Cover images: Thomas Pajot / Alamy Stock Vector

pid_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

For John R. Rittelmeyer (19552019)

Preface

When my editor at First Things magazine suggested that I write a book about the baby boomers modeled on Lytton Stracheys Eminent Victorians, my estimate of his literary judgment, which I already rated highly because he printed my stuff, increased further. Eminent Victorians is a great book and, what is far more rare, a successful book. It hit what it aimed at. The Victorians had less influence on the world when Strachey was done with them. To do the same for the boomers was so obviously a good idea that I forgave my editor for elaborating on my suitability for the project by saying, Youre like Strachey; youre an essayist, and youre mean.

Eminent Victorians, for those who dont know it, was a collection of short biographical portraits published in May 1918, in the waning days of World War I, and never was a book more fortunate in its timing. It arrived in London shops just as Germanys spring offensive was faltering and American troops were finally arriving in numbers on the western front. As victory became close enough to contemplate and the psychological clench of wartime began to relax, the people of Britain started to ask themselves whether it had all been worth it.

Among those who concluded that it had not, there were many who saw the war as something worse than an error of judgment. Their suspicion, which Stracheys book put into words for them, was that the men who had brought Britain into the war and all the values those men had believed in must have been not just mistaken but fundamentally corrupt.

The four Victorians Strachey chose to attack had always been held in high esteem: Cardinal Manning, the Roman Catholic archbishop known for his social work; Thomas Arnold, the Rugby headmaster who invented the English public school as we know it; General Charles Gordon, the martyr of Khartoum; and Florence Nightingale, the one modern readers have heard of. To blame these national heroes for the Somme was a stretch, and in Nightingales case positively perverse. Nevertheless, Strachey attacked his targets with an oedipal fury, perhaps because these four figures, though long dead, felt oppressively present to him as architects of the world he inhabited.

It was not what the Victorians believed that Strachey rebelled against so much as their believing in anything at all. Strachey himself was a pure aesthete. Only two things I find amuse me, he once told Leonard Woolf, wit and the flesh. This insouciance eventually worked against his credibility when it became clear he had no alternative set of values to offer, but for Eminent Victorians his ironic pose only helped. It gave the book a light touch. The Victorians could survive being proven wrong. They could not survive being made to look ridiculous.

The first edition sold out nine printings in two years. It did not matter that many of the things Strachey wrote were simply false, as he happily admitted. War-weary book buyers cared about only one thing: the people who had gotten the country into such a mess deserved a shellacking, and Strachey had given it to them. As Cyril Connolly once said, the nice thing about the 1920s was that in those days, whenever you didnt get on with your father, you had all the glorious dead on your side.

And those of us who would attack the baby boomers, what do we have on our side?

I have no quarrel with my parents, who were both born in the 1950s. My father, who died while this manuscript was being written, was a liberal Southern lawyer of the Atticus Finch type and, like Atticus, beyond reproach. My mother was a bit of a hippie when she was youngershe majored in pottery at a college that no longer existsbut the only thing I have to reproach her for on that score is that I never learned how to put on makeup. They were wonderful parents, and Im very grateful to them.

Whatever my editor at First Things might say, I dont feel this book was written in a spirit of meanness. As I was drafting a list of boomers to profile, I found that I had no interest at all in writing about buffoons and psychopaths, however colorful some of them were. Instead, I was drawn to the boomers who had all the elements of greatness but whose effect on the world was tragically and often ironically contrary to their intentions. Their destructiveness came from their virtues as much as their vices. I was going to spend months, even years with these people living in my head. I did not want to pick anyone for whom I felt contempt.

On the other hand, I do feel some of the moral indignation that animated Stracheys readers. I graduated from college in 2008 already with a sense that the millennials were, in some deep spiritual sense, a dispossessed generation. Then the financial crash came, and the sense of dispossession became more literal. Those were lean years for me and my friends, made worse by the burden of student debt, which boomers urged us to take on as much of as we could in order to go to the best school that would have us. The recessions headwind on our careers has put millennials years behind in achieving the standard material indicators of adulthood, like marriage and buying a house. But as long as millennials are trapped in the Tinder cycle or on the career track and putting off childbearing anyway, what would we need to buy a house for?