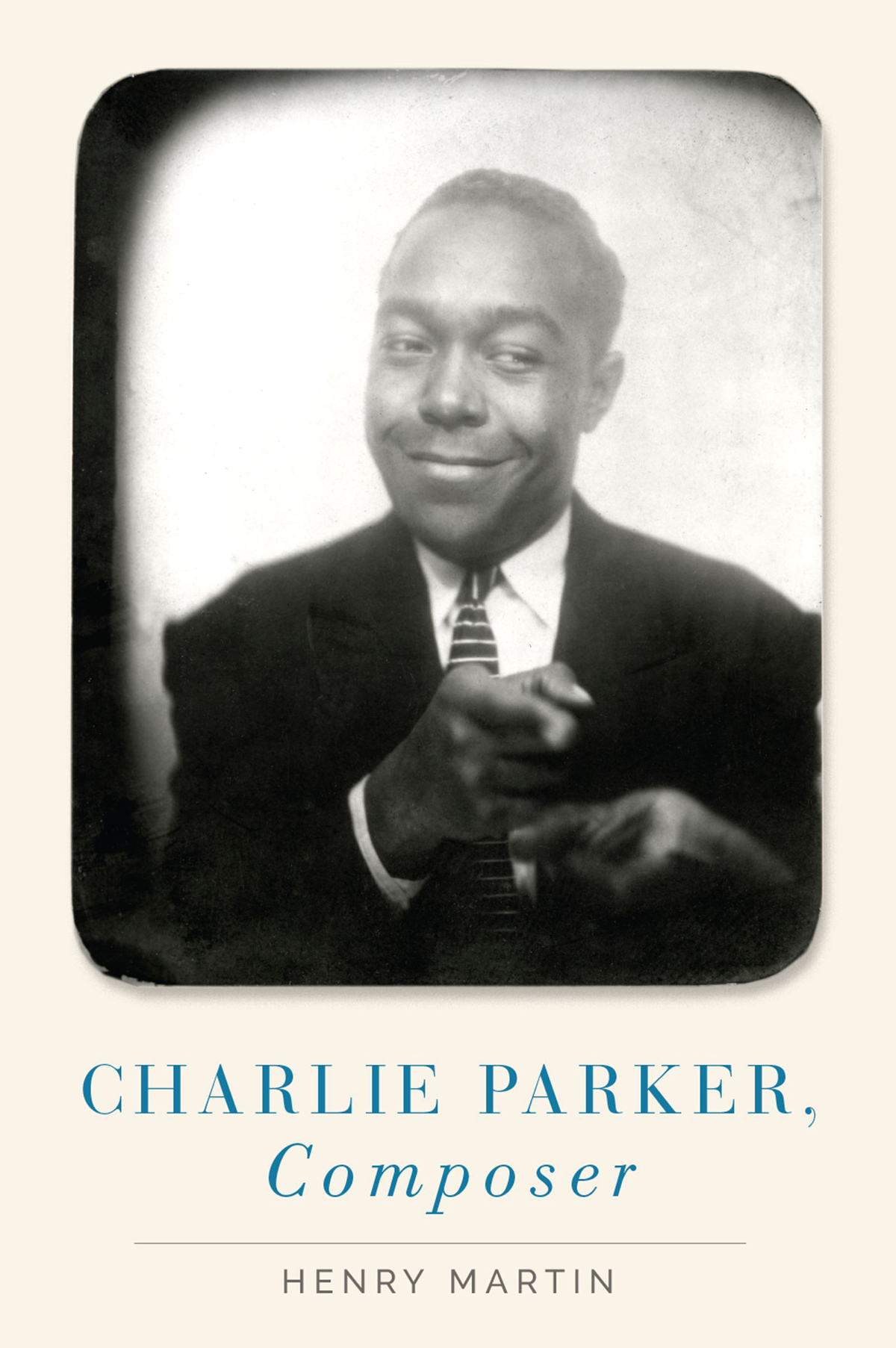

Charlie Parker, Composer

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Martin, Henry, 1950 author.

Title: Charlie Parker, composer / Henry Martin.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2020. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019042474 (print) | LCCN 2019042475 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190923389 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190923402 (epub) |

ISBN 9780190923419 (online)

Subjects: LCSH: Parker, Charlie, 19201955Criticism and interpretation. |

Jazz19411950History and criticism. | Jazz19511960History and

criticism. Classification: LCC ML419.P4 M38 2020 (print) |

LCC ML419.P4 (ebook) | DDC 788.7/3165092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019042474

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019042475

To Ben Givan

Contents

Examples

Musical example credits are to be found on pages .

Tables

Charlie Parker has long been appreciated as one of the consummate jazz musicians of the twentieth century. He helped transform swing-style jazz, a mainstay of popular culture, into bebop, a thrilling if sometimes labyrinthine maze of abstractions that may have perplexed and dismayed older jazz fans, but excited those attuned to the new music. At least as much as any other jazz musician, Parker has been called that much overblown term, a genius, largely because of his outstanding accomplishments as an improviser. But as brilliant as his solo skills were, Parker was also a significant jazz composer, an aspect of his musicianship that has not been sufficiently investigated and appreciated. My focus in this book is on the analytical interest and general significance of his compositions; from time to time, I will also link them to relevant events in his biography to help deepen our understanding of his accomplishment. Further, Parkers 100th birthday on August 29, 2020, is a significant milestone, an opportunity to celebrate his art and his exceptional contributions to the establishment of modern jazz.

A study of Charlie Parker as composer might come as a surprise to many. While Parkers reputation is secure as one of the greatest and most influential of jazz improvisers, he has never been seen as a particularly significant composer. Or perhaps a more positive way to state this is that given Parkers preeminence as an improviser and as a founding father of bebop, his bebop themeswhile admired and often playedhave inevitably taken a back seat to his improvisations. I feel that this is an imbalanced appraisal, that Parker is an important jazz composer whose influence and skill have yet to be sufficiently acknowledged and appreciated. Parkers work in this area offers, succinctly, insight into his total musicianship as well as early bebop style more generally. In this book, I plan to balance our estimation of Parker as an improviser by examining his compositional output, showing its ingenuity and relationship to his improvisational skill, while at the same time locating each composition chronologically in Parkers life. My discussions emphasize music-theoretical and music-historical approaches to the music, but in treating Parker as a composer I also hope that perspectives on the nature of jazz composition will emerge.

Among the questions explored are the following:

1) Parker wrote numerous bebop tunes, created self-standing and well-known melodic fragments, and made recordings that were improvised with no prior thematic material; should we call them all compositions?

2) Is it correct or fair to view Parkers tunes as throwaways, merely providing harmonic/formal frames for improvisation and copyright royalties?

3) How do Parkers compositions amplify our understanding of his total musicianship?

4) Parker normally used the harmonic and formal layout of previously composed songs as the basis for his new tunes. What are the implications of this practice? Did he ever deviate from it?

5) Which of Parkers blues tunes depart from the form of the classic blues?

6) Can we understand why Parkeras far as we can tell from gigs that were recordeddid not perform in public many of the pieces that he wrote and recorded?

7) Which of Parkers tunes have remained popular among jazz musicians? Is there a rationale for their selection?

8) In what useful ways can we categorize Parkers pieces?

9) To what extent can we view Parkers approach to composing evidence of a general shift during the later 1940s regarding jazz composition?

10) What is the significance of Parkers desire for new musical challenges during the last few years of his life?

Parker ranks as one of the most important jazz composers of his era simply by virtue of the continuing popularity of his best-known tunes. Performed widely, they are considered seminal within the jazz repertory. Among the most familiar are Nows the Time, Moose the Mooche, Blues for Alice, Confirmation, Ornithology, Billies Bounce, Anthropology, Cheryl, Relaxin at Camarillo, Scrapple from the Apple, Au Privave, My Little Suede Shoes, and Yardbird Suitetunes well known to jazz musicians and fans. Even Parkers lesser-known pieces, however, merit attention. These include such intriguing works as Cardboard, Cool Blues, Barbados, Dewey Square, Ah-Leu-Cha, Perhaps, Bloomdido, Back Home Blues, Swedish Schnapps, Charlies Wig, and Chi Chiall worthy of study.

Some pieces became virtual trademarks, for example, Ornithology, with its punning reference to the study of Bird (Parkers nickname). When he performed in various cities with local musicians, it was convenient to call pieces easy for everyone to play. Such a circumstance may underlie the many performances of his riff tune Cool Blues, which consists of a single four-bar phrase played three times over the changes of a C blues. Like Ornithology, this piece became something of a trademark.

An advantage to studying Parkers complete compositional oeuvre is the added insight we obtain into jazz composition itself. While not deviating from the standard 12-bar and 32-bar forms, he sometimes worked with as few as four bars of music. Such incomplete pieces might be viewed as flouting the traditional expectations of a composer, but they also remind us that bebop was an essentially modernist movement, one that didnt always rely on the popular songs heard in earlier styles of jazz; as such, Parkers minimalist work anticipates radical forms of modernism that flowered in the later 1950s. He also directly improvised pieces that were issued as recordings and copyrighted with Parker as composer. Should such works be considered as Parker compositions, although they were not traditionally written? It is here where the oral aspect of jazz challenges the concept of a music composition as understood in the Western tradition, an idea to be addressed in the Introduction and in .