Ron Frankl - Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer

Here you can read online Ron Frankl - Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Infobase Publishing, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer

- Author:

- Publisher:Infobase Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Charlie Parker almost single-handedly revolutionized the jazz world by perfecting the style known as bebop. This amazing talent of the music world played with Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and other giants of jazz, but would lose everything to a heroin

Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2014 by Infobase Learning

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For more information, contact:

Chelsea House

An imprint of Infobase Learning

132 West 31st Street

New York NY 10001

ISBN 978-1-4381-4518-1

You can find Chelsea House on the World Wide Web

at http://www.infobaselearning.com

It was supposed to be his big comeback, his return to the spotlight after several years of personal and professional problems that had practically ended his career as a jazz musician. As 34-year-old Charlie Parker waited to take the stage on March 4, a Friday night in 1955, he knew that his next several performances could begin a new era in his life, one in which he might reclaim the success he had won only a few years earlier. He also realized that his weekend engagement at Birdland, New York City's foremost jazz club, might be his last chance.

Birdland, billed as the Jazz Corner of the World, stood on Broadway near 52nd Street, in a small patch of midtown that was the place to hear jazz. Back in 1949, when the club first opened its doors to the public, Parker was extended the honor of having the night spot named after him. It had seemed logical to call Birdland after Parker, whose nickname of Yardbird was often shortened to Bird by his adoring friends and fans. After all, he was the greatest young talent in jazz.

Just a few years prior to the opening of Birdland, when Parker was still in his mid-twenties, the alto saxophonist had forever changed the direction of jazz with his revolutionary approach to harmony and rhythm. This new style, called bebop (or simply bop), departed from the dance-oriented "swing" style of jazz that had been popular for a decade. Bebop stressed improvisation over conventional melody and featured unusual harmonies and rhythmic shifts. It demanded the full attention of the listener and was anything but background music. At its best, bebop was daring, thrilling music that was both intellectually and emotionally challenging. And when he was healthy and happy, nobody played bebop better than Charlie Parker.

Parker's music was the perfect balance of creativity, virtuosity, spontaneity, and emotion. Although his sound was often imitated, it was seldom surpassed. Every young jazz musician who heard Parker's music was in some way influenced by his ideas. Even some of the older, more traditional-minded musicians were inspired and revitalized by his stunning innovations.

Parker was not bebop's only pioneer. A handful of other young musicians, most notably trumpeters Miles Davis and John ("Dizzy") Gillespie and pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, helped usher in the new sound. But Parker was regarded as the most talented musician of the bebop revolution; and even though he was far better known among jazz musicians and serious fans than with the general public, he seemed to have the brightest of futures.

One of the greatest and most popular jazz trumpeters of all time, Dizzy Gillespie, is pictured outside Three Deuces in around 1948.

Source: Library of Congress, William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, LC-GLB23-0327 DLC.

Parker's popularity increased slowly through 1948, and by the following year his records were selling well for the first time in his career. He and his quintet also reached thousands of listeners through their exciting early morning performances broadcast weekly on the radio from the Royal Roost nightclub. The public, it seemed, was finally beginning to appreciate the musical genius of Charlie Parker.

Parker was enjoying his growing fame. In May 1949, he made a triumphant concert tour of Europe, where he was greeted by wildly enthusiastic audiences everywhere he performed. Six months later, he realized a long-standing dream by recording with a string orchestra. Among bebop musicians, only friend and former bandmate Dizzy Gillespie surpassed Bird in popularity as 1949 drew to a close.

On December 15, 1949, Birdland's opening night, Parker had stood at the pinnacle of his popularity. A large crowd jammed the club to hear an all-star roster of jazz performers. Included in the show were saxophonist Lester Young, Parker's idol when he was a teenager; another brilliant saxophonist, Stan Getz; and an exciting new singer named Harry Belafonte. Headlining the bill was Parker himself.

Yet only five years later, on a Saturday night in March, Parker was desperately trying to reestablish himself in a jazz scene he had helped create. Many of his former associates had become major concert, nightclub, and recording stars, playing music that was often only a weaker version of his own ideas. Musicians were growing rich from the style and vision of Charlie Parker, yet he was homeless and often had to stay with friends for days or weeks at a time. On several occasions, he even slept on park benches and subway trains.

By March 1955, Parker was a forgotten man to many in the music world. It was a tragic situation, made sadder still by the fact that he was largely to blame for his own troubles. Years of erratic behavior, worsened by heroin and alcohol abuse, had severely damaged his reputation in the music industry, and it had become difficult for him to find opportunities to perform.

Parker's heroin use had also gotten him in trouble with the New York City Police Department. As a result, in 1951 he had lost his cabaret card, a permit issued by the New York State Liquor Authority to all performers who wished to work in New York City nightclubs. Even though Parker was not convicted of drug possession or any other crime, the police recommended that his cabaret card be suspended. Without it, he could not work in any of the city's night spots.

By the time Parker was finally issued another cabaret card in 1953, his reputation and career had been ruined. He had landed the March 1955 gig at Birdland only by pleading with his booking agent, who had finally agreed to arrange the saxophonist's return to the stage. This show would mark Parker's first appearance at the nightclub since a troubled engagement the previous summer, during which he had fired the accompanying string orchestra in mid-performance! For that unprofessional outburst, he had been barred from performing at Birdland.

Parker's personal life was also very troubled. He and Chan Parker, his common-law wife, had split up at the end of 1954, and he seemed entirely lost without her. His years with Chan had provided him with the only period of domestic happiness and stability he had experienced since childhood; she had seemed to understand him better than any of the other women in his life. Without her, he seemed to lose the will to fight the troubles that now all but overwhelmed him.

As if all these problems were not bad enough, Parker's health was also beginning to fail. He was once the hardiest of men, but years of overindulgence in heroin, alcohol, and food had taken their toll. He had suffered from heart trouble for years, and even though he had finally managed to kick his heroin habit, the liquor he used as a substitute worsened his severe stomach ulcers.

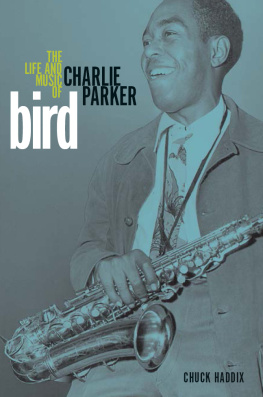

Charlie Parker plays at Three Deuces in August 1947.

Source: Library of Congress, William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, LC-GLB23- 0689.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer»

Look at similar books to Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Charlie Parker: Musician and Composer and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.