Copyright 2021, William D. LaRue

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Published by Chestnut Heights Publishing

ISBN 978-1-7322416-4-0 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-7322416-2-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-7322416-3-3 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020924238

First edition.

Contact the author at williamlarue.com

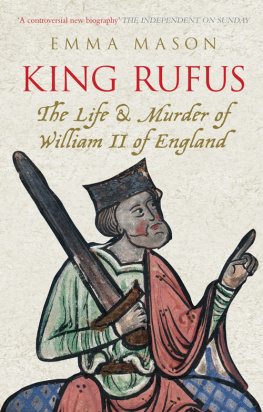

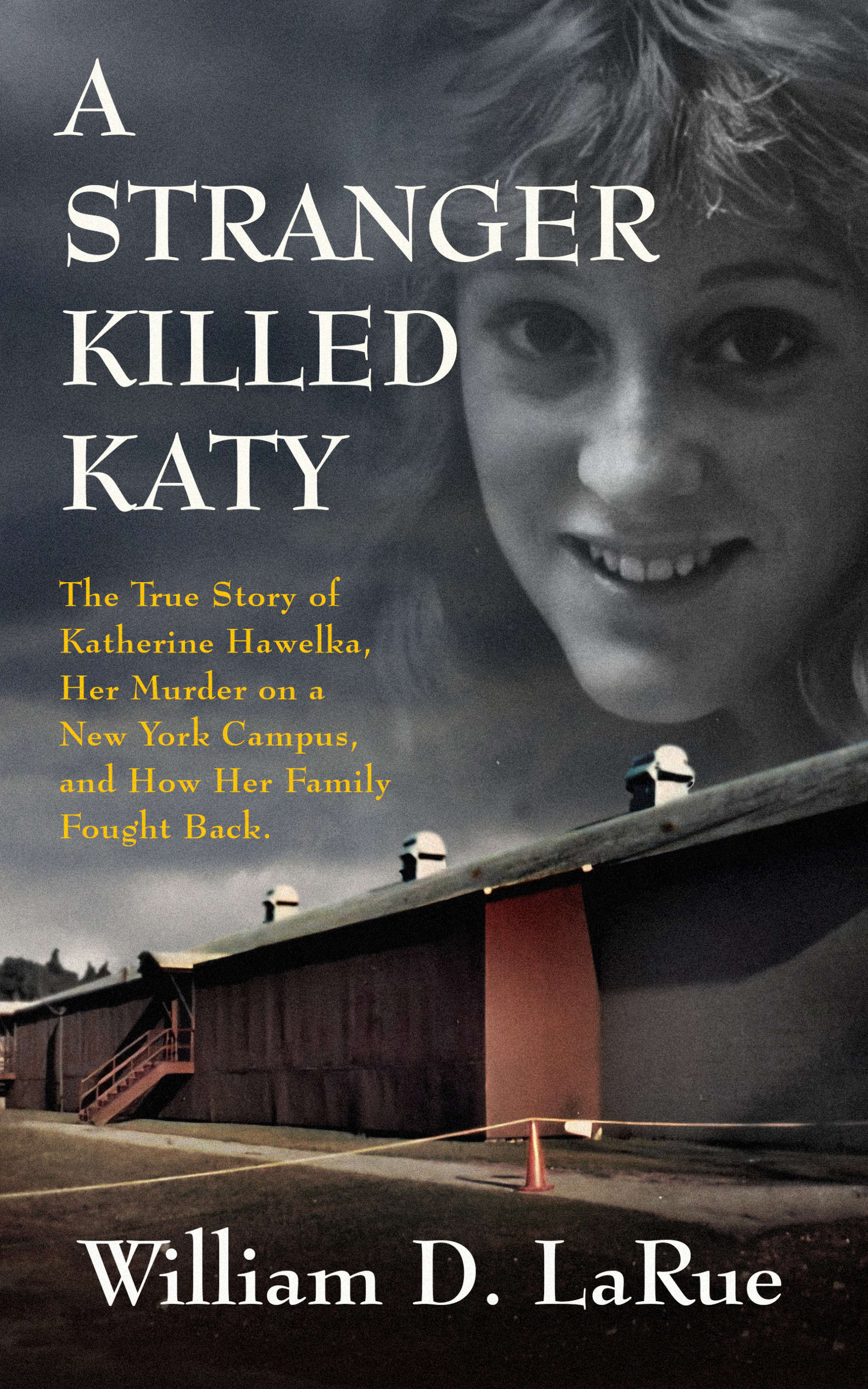

Front cover: Katherine Hawelka and Clarkson University's Walker Arena. (Hawelka family/Potsdam Police Department photos.)

Back cover (print versions): Brian McCarthy leaves Potsdam Village Court, escorted by Potsdam Police Investigator John Perretta, left, and Officer Gene Brundage on Friday, August 29, 1986. (Mary Ellen Banta, The Post-Standard photo.)

Cover design by www.ebooklaunch.com

e-book formatting by bookow.com

Chapter 1

The Attack at Walker Arena

R obert J. Warren Jr.s headlights caught something strange in the inky darkness as he drove southwest on Route 11 in upstate New York at around 10:15 on the evening of August 28, 1986. Warren hit the brakes on his GMC pickup and managed to screech to a stop a few feet before he would have struck a man sitting partly in the roadway.

The 24-year-old Warren had been heading home to Morristown, New York, after dropping off his wife at her parents house in nearby Winthrop. He was now alone in the truck as he studied the man, who looked to be in his mid-20s with a medium build, dark hair, a scruffy beard, a dark jacket and beige work boots.

Seconds later, the man jumped up and ran over to the truck.

Do you have a problem? What are you doing? Warren asked.

The stranger in the road said he was going to the village of Potsdam, about 10 miles up ahead, and asked if Warren could give him a lift. In the mid-1980s, it wasnt considered uncommon or particularly unsafe to pick up a hitchhiker heading toward Potsdam, home to a college and a university. In this rural region just south of the Canadian border, public transit was all but nonexistent. Young adults often used their thumbs to get from one distant town to another.

Warren invited the man to get in.

The hitchhiker climbed onto the passenger seat and introduced himself. Warren only caught his first name: Brian. The man smelled of booze, but he seemed friendly, if perhaps a bit wired. As Warren resumed driving toward Potsdam, his passenger did most of the talking, making a point to brag that his family was prominent in the Potsdam area and owned numerous businesses there. Warren heard him say something about being related to the Snells.

The hitchhiker also let it be known he had spent much of that day drinking, snorting coke and smoking marijuana, and he still had about 4 ounces of pot on him.

Do you want to smoke a joint? he asked.

Warren shook his head. No, he said, I dont do that anymore.

Warren was a bit amused by all of this until the hitchhiker confessed he had a violent confrontation that evening at Chateaus Restaurant and Bar in Winthrop. He got into an argument with a man who accused him of stealing three dollars left on the bar. Then, the hitchhiker said, he shot him in the leg, adding that this guy would be dead by 4 that morning.

As if to offer proof, he said he was packing .25-caliber and .357-magnum handguns. He asked if Warren wanted to see one.

Warrens hands tightened on the steering wheel. No, he said.

By the time the pickup entered Potsdam's village limits around 10:30 p.m., Warren couldnt wait to get rid of his passenger. Warren pulled the vehicle to the curb at the corner of Elm and Market streets near Robinsons Market in the heart of downtown. After quick goodbyes, the hitchhiker jumped out, crossed Market Street, and disappeared into crowds of young people heading in and out of the restaurants and bars.

Thoroughly shaken, Warren decided he had to warn the cops before this man killed someone. Although there was a village police station around the corner on Raymond Street, Warren continued on Route 11, going past the Clarkson University campus and driving south for several more miles until he pulled into the driveway of a New York State Police barracks. It was just before 11 p.m.

A trooper on duty made Warren write out a statement describing the encounter with the hitchhiker. Warren wrote down as much as he could recall. Warren didnt have a last name for Brian, but he remembered other details, such as the reference to the Snells and how the man was wearing a silver-colored watch with a silver elastic band.

At that point, state police had no report about any bar altercation or anyone being shot that night in Winthrop. And with Warrens somewhat vague description, police didnt have much to go on. However, troopers said later, they relayed Warrens statement to Potsdam police and kept an eye out for anyone matching the hitchhikers description in hopes of questioning him.

Unfortunately, the timing couldnt be worse for locating a stranger in Potsdam. Thousands of out-of-towners had arrived that Thursday for the fall semester at Clarkson and at the State University College at Potsdam, adding another 8,000 or so students to the villages permanent population of about 10,000. With most classes not starting before Tuesday, thousands of students had descended on downtown bars and restaurants.

Police patrolled the village streets until well after midnight, but none of the officers recognized anyone matching the description of the hitchhiker.

In the hours that followed, police would wish so desperately they had.

Potsdam Police Officer John Kaplan began his shift the evening of August 28, 1986, at around 8. He zipped up his denim jacket, grabbed a two-way radio, and headed out the door of the police station. Kaplan walked briskly to Market Street, the main thoroughfare in the business district, to begin his patrol of downtown and nearby streets. By then, the sun had disappeared behind the long row of sandstone and brick buildings, and the temperature had dipped to 50 degrees Fahrenheit. A light breeze made it seem even chillier.

The 25-year-old rookie cop, who grew up in Potsdam and graduated from Potsdam State in 1982, was assigned this evening to work a foot beat. With his youthful looks and casual clothing, he blended in easily with the college students. He could remain unnoticed until he had to respond to an incident. Backing him up were two uniformed officers circling the village in a marked patrol car.

Kaplan spent much of his time on the lookout for underage drinkers trying to slip into the bars. The previous November, the New York State Legislature raised to 21 the legal age to purchase alcohol in New York. Underage drinkers tried to get around the law by using fake IDsor by borrowing a legitimate ID from someone 21 or older.

Strangely, while it was illegal for bars to serve an underage person, it wasnt against state law at the time for someone under 21 to drink the alcohol. The students only got in trouble for underage drinking when they used a fake ID; for that, they could face a $100 fine. It could turn into a felony charge if they altered the birthdate on a driver's license. When Kaplan saw someone using a fake or borrowed ID, he confiscated it, but he didnt always ticket the offender. He often issued a warning if the person seemed genuinely remorseful and promised not to try this again. Like many police officers in the 15-member department, Kaplan wasnt a big fan of the new drinking law. If people were old enough to vote or to serve in the military, Kaplan thought they should be old enough to legally buy a beer. But the law was the law, and Kaplan knew it was his job to enforce it within reason.